A LONG LOST LOVE: AUGUST

“A boy’s will is the wind’s will,

And the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts.”

– Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

“I was never so sure of anything in my life. The moment you left me, I knew

I must find you again, quickly. I’ve found you, and I’ll never let you go”.

There’re a great many sayings about the thing called love – quotes without which we mightn’t know what we’ve stumbled into, adages against which we might measure our newfound happiness, or proverbs in which we might find comfort in loss. ‘One cannot love and be wise’, ‘Love is patient, love is kind’, ‘Distance makes the heart grow fonder’, ‘Right person, wrong time’… the list goes on, and it runs the gamut of emotions and experiences. (I’d be remiss if I didn’t add “We’ll always have Paris”.) And, though love is as abstract an idea as was ever conceived, most of them make sense, if only conceptually – we understand the words and we see the logic in them. But, with a little luck on one’s side as time it goes by; should we hold onto that fleeting feeling long enough to call it love or, as often we do, should we hold onto it a little too long after it’s gone, the words of such sentiments might start to ring a little more true. Of course, some are such sentimental baloney that they’re rightfully relegated to being printed on canvas and sold on Etsy only to be strung up on the wall next to your new combination microwave. Some seem pressing on paper, but in practice only serve to sugarcoat a pill we’re unwilling to swallow. There are those, however, and I believe they’re the many, that, saccharine as they might seem, really do just capture the damn feeling exactly.

With that being said, there is one saying that I could never quite make heads or tails of. ‘We accept the love we think we deserve’. I can see it in cursive above a bathroom sink, although that would make washing your face every morning an awfully depressing task. Still, I’d be lying if I said it hasn’t sometimes come to mind while washing up before bed. How do we know what we deserve? Do we even deserve anything? Should we think we deserve everything? Does it even matter? The inference is, it seems, that faced with another’s love one thought themselves undeserving of, one would choose not to hold onto it for dear life, but would in fact choose to run. And that’s where you lost me. I don’t buy such tragedy. I simply wouldn’t. I couldn’t! Or so I thought until I watched the tallest tragedy in the history of cinema, a tale so tall I could scarcely believe it, a film whose shadow looms large over each and every romance since, Robert E. Sherwood’s story of love and loss in war and peace, and my August movie of the month: 1940’s ‘Waterloo Bridge’.

The picture opens on the third of September, 1939, on the eve of World War II. Roy Cronin, a greyed and seasoned colonel (played by Robert Taylor), is on his way to the front in France by way of Waterloo Station. As his driver turns onto Waterloo Bridge, Cronin asks him to stop, and gets out of the taxi. He tells the cabbie to meet him on the other side, and, wandering slowly to the middle of the bridge, turns to face the twilit city. Roy retrieves a billiken (a charm doll) from the pocket of his overcoat, and holds it tightly as he looks out over London and up into the stars. “Do you think you’ll remember me?”, sounds her voice in his head. “I think so. I think so. And for the rest of my life”, comes his reply. The camera pushes in, and as the people push past, we slowly dissolve a quarter century back, to the summer of 1914, to the eve of the First World War, to a younger Roy Cronin, not yet a colonel but a captain; one of bright-eyes and a bushy-tail, one whose youth is still ahead of him. And so our story begins.

It’s the night of an air raid, and the city is scrambling for shelter. Seeing the stripes on Roy’s sleeve, a company of ballerinas ask him the way to the underground. He points them towards the station, and the troupe takes off, save for one ballerina, a Miss Myra Lester (played by Vivien Leigh), who is left behind when her bag splits open. As she picks up the pieces of her belongings, Roy ushers her off of the bridge; he grabs her arm but she won’t go with him, not until she’s found the last of her things: her lucky charm, a little billiken.

With Myra separated from the rest of her troupe, the two stick together, and soon find themselves squashed like sardines beneath Waterloo Station. As they talk of the least important and most interesting things, it becomes clear that Roy sees something in Myra. Myra, for her part, though a very willing air-raid companion, seems unable to see the suggestion of destiny that lights in his eyes. What also becomes clear, as the raid rages on, is that which, perhaps, informs the former – that these two persons are two markedly different people. When Myra points at a poster of Madame Kirowa’s International Ballet (of which she is a part), she talks of the strength and discipline needed to be a ballerina. When Roy talks about the war, he speaks of the excitement, and his fascination with the unknown, an unknown which hides around every corner. Though we won’t learn it till later, Roy is from privilege, and has led an easy life among the upper crust of British society. Myra, on the other hand, whose backstory we never really know, is without family, and it appears without much in the way of hope outside of her life in the ballet. We see that where Roy is romantic, Myra is pragmatic. To Myra, life is a duty; to Roy, it is an opportunity. And, such facts are not lost on the two leads, either. When Myra questions Roy for his rose-tinted view of the war and all its excitement, he replies, “You’re rather matter-of-fact, aren’t you?”, to which she agrees, then smiles, teasingly, and adds, “You’re rather romantic, aren’t you?”. But before Roy can respond, the all-clear signal is given, and as London returns to normal life (at least till tomorrow), the lives of our two leads are re-set to continue down their own, separate paths.

As they surface from the shelter and emerge into darkness, they weigh up their chances of meeting again. With Roy off to France the very next day, Myra concedes that, “it isn’t very likely, is it”. And, with the ballet soon to set sail for America, Roy has no choice but to agree. As Myra hurries into a taxi, to make it to her performance on time, Roy tells her he wishes he could be there. She invites him, but, Roy has a colonel’s dinner, and “it takes a lotta nerve to miss a colonel’s dinner”. After a moments silence, Myra reaches into her bag and offers Roy her billiken, hoping it will bring him luck. He protests, but, with a smile, she insists. As the car pulls away, Roy is left standing, watching; holding on to a lost feeling of promise and her little toy charm. After a dissolve further into the evening, with the ballet well underway, we see a gentleman arriving late being shown to his seat, and… Well, I’ll let you guess who it is.

There lasts a mere six minutes in-between Myra’s introduction and the dissolve to the ballet. And in those six minutes, there is no real ‘romance’. That is, there’s no rapid fire flirting or obviously contrived chemistry; there fly no sparks between them to be seen from space and today was not the day the earth stood still. It is just two people, whose paths happened to cross, if only for a moment. Such moments, I am sure, we all have shared. Whether running through an airport in Rome or running nowhere fast in a long line for the loos, our paths are constantly crossing with the most unlikely of people at the most unlikely of times and places. Though, pleasant as those moments may be, they remain, more often than not, only moments, and our lack of imagination prevents our ever knowing where such moments might possibly lead. But where we, like Myra, might see her and Roy’s coming together as a fact that can be chalked up to chance (and a German air raid) and written off as nothing more, Roy feels the long arm of fate reaching in. It is an extraordinarily sincere opening, and it is all the more magical, and romantic, for its innocence. All it takes now, as always it does, is for someone to make the leap.

After smiling like a schoolboy every time she’s on stage, the ballet comes to a close, and Roy writes a note for Myra backstage. She receives it, but before she has a chance to open it alone, the tyrannical Madame Kirowa (to whom a romance is inexcusable) makes Myra read out Roy’s request in front of the entire troupe, and forces her to write a refusal. The note is returned to Roy who, fearing he’s misread the stars in the sky, turns to walk away in defeat. That is, until he is stopped by fellow ballerina, and Myra’s best friend, Kitty, who asks him the time, and place, and promises that Myra will be there.

I will refrain from employing a string of superlatives in an attempt to articulate my feelings towards the scene that follows, and will instead say this, and only this: their night together is the type of night that Hollywood has made us believe in. And it ends not with any grand declaration of love, nor even a kiss… It ends, instead, with the most romantic pièce de resistance of any dinner/dancing scene I’ve ever seen. As Roy toasts “To you. To us”, towards the end of their dinner, the maître d’ announces the final dance of the evening, the farewell waltz. They rise, along with the rest of the restaurant, and as ‘Auld Lang Syne’ sounds from the band beside them, the lights dim, and soon the only light left comes from the candle on each table. Then, slowly, one by one, as the waltz it goes on, each candle is blown out, until there’s little light left; too little to see the people dancing around you, just enough to see the partner dancing with you. The scene is a showstopper, and while it could so, so easily have fallen into gimmickry, it is handled with such grace and humility, that it is more than just a show-stopping scene – it is the most brilliantly unassuming, and moving portrayal of ‘falling in love’ in movie history.

For the majority of their night at the Candlelight Club, Roy assumes a more traditional, leading-man persona. He knows the best spot in town, has a table reserved for two, and knows just the right wine to order with dinner. He even puts his hand on hers before the dinner arrives. But, while she admits to being glad at seeing him again, he senses a reservation, and she confesses that there is:

Roy: What? What-Why

Myra: [Pauses] What’s the good of it?

Roy: You’re a strange girl, aren’t you. What’s the good of anything? What’s the good of living?

Myra: That’s a question, too.

Roy: Oh, no. I’m not going to let you get away with that! The wonderful thing about living is that this sort of thing can happen.

And, with this exchange, order is restored, and the dynamic between the two is so brilliantly underscored. Roy realises that it is not a ‘role’ he must play simply to win her over, but that he must prove his love, their love, to her, if it’s to last long enough to call it so. And, in the process, he is reduced to the headstrong impulsiveness of youth. This is the role that Taylor, as Roy Cronin, will play for the remainder of the film – that of the boy trying ever to catch up with his (& her, thus their) future. It is on Leigh’s shoulders, as Myra, that rests the burden of change. It is through her character that the drama will play out, for Roy promises to pull her out of her defeatist ways, both for better, and for worse. It is she who will have to deal with the consequences of their love; to bend or break with the obstacles that life, and the war, will throw in their way. They know, as we do, that their journey together promises to be all but an easy one. And this sentiment is only exacerbated by our feeling that neither of the two have driven down this particular road before, and our knowledge that, often, nothing can prepare you for a fate that awaits you.

The plot thereafter follows a fairly formulaic arc for a Hollywood romance-drama. I shan’t spoil it, for the sake of fairness, and I won’t trivialise the tale by attempting to put it into words. Suffice it to say, after Roy’s due date at the front is postponed by a day, the two decide to get married, but war-time red tape and peace-time regulations prevent them from doing so. After spending the rest of the day as groom-and-bride-to-be, Roy is shipped off to the front, and when Myra follows to see him off at the station, she misses her performance and is fired from the ballet. Kitty, in an attempt to stick up for her friend, confronts Madame Kirowa and is caught by the axe, too. Resisting the temptation to turn to Roy’s family for support, Myra struggles to get by, and Kitty eventually turns to prostitution to try and support the both of them. Myra holds out, and eventually receives word from Roy’s mother, who is anxious to meet her soon-to-be daughter in law. But, on the afternoon of their tea, Myra reads the news that Roy has been killed. Unable to stomach the shock and overcome her emotion (or articulate the news to his uninformed mother), Myra and Lady Margaret get off on the wrong foot and, failing to see what her son sees in the incoherent and unstable Myra, Roy’s mother swiftly leaves. Reading the cards that have been dealt her, Myra sees no other option to survive her circumstances, and follows Kitty down the dark alley. After a year or two passes, Myra wonders into Waterloo Station (where she goes to pick up soldiers on leave) and, as she stands by the barriers, scantily clad and smiling at strangers, we see her face start to turn. Who should she see walking towards her in the distance? She sees Roy, of course. And, while Roy is more than over the moon at seeing their stars realign, and keen to catch up with the future they were promised, Myra is forced to confront her ‘morality’ in the presence of her lover, and finds herself, ultimately, unable. It is here, with things having gone from good to bad, and bad to worse, that the thread of their love begins to unravel. It is here that one starts to reckon with the reality that we don’t necessarily accept the love that we do deserve, but only the love that we think we deserve. And, with that key discrepancy, with the addition of that one single word, a word that reflects solely on ourselves; therein lies the tragedy. Where their story ends you will have to see for yourself, and, even though LeRoy lets us in at the jump (since the film is all a flashback), don’t be surprised when the rug is pulled right out from under you.

I will admit that, when put in words, the story might seem a little trite or contrived. The 1940 film, directed by Mervyn LeRoy, deviates from the original play (written by Robert E. Sherwood), and also from the original film adaptation from 1931 (directed by James Whale). It is increasingly melodramatic in comparison to the original text, and is much less explicit about the level of despair and destitution reached by Myra and Kitty (due to the introduction of the Hays Code [censorship] in the intervening years) than the original film. But, LeRoy’s film is salvaged by its sincerity, through which it achieves a greater emotional depth than either of the other two. This is, in part, due to LeRoy’s direction, whose journeyman approach is largely invisible. He doesn’t dwell on the moments that are sentimental; he shows us the story as it is, without taking ‘advantage’ of the material, and his shot selection includes an emphasis on classically romantic close-ups, which our two leads revel in. Taylor, who was known to be both incredibly handsome and frustratingly wooden, turns in a remarkably flexible performance as a man in love no matter the odds. It is, however, Vivien Leigh who rightfully receives top billing. She, to quote the late Bosley Crowther, “shapes the role of the girl with such superb comprehension, progress[ing] from the innocent, fragile dancer to an empty bedizened street-walker with such surety of characterization and creates a person of such appealing naturalness that the picture gains considerable substance as a result”. Myra’s is a role with such range and, if such a thing need even be said of such an exceptional actress, Leigh’s casting as her is a match made in heaven. She employs every bit of grace and mobility to be found in her body, and in the expressiveness of her face we see the cinema’s greatest tragedy from a front row seat.

Movies are the medium of chance, and, while most movies incorporate an element of serendipity, or mere coincidence (depending on how you look at it), none makes use of it more than the romance genre. Whether romance-drama or romantic-comedy, a mix of both or a blending of neither, a romance relies on the chance meeting between two people. That meeting is known as the meet-cute, and the more improbable, yet somehow inevitable, it seems to be, the better it is. And, like all the others, ‘Waterloo Bridge’ celebrates such serendipity, and its story could only stem from the chance meeting of our two lovers atop the titular bridge. But, unlike other entries into the genre, ‘Waterloo Bridge’ shines a light on the fragility of destiny. Instead of taking it for granted, it acknowledges the impossible odds of these two people meeting, and uses it, at first, to drive the story forward, but eventually, to drive a wedge between them that can never be crossed. Myra and Roy aren’t held apart by any superable barriers, but by the long arm of fate – the very thing that brought them together in the first place.

And so, as the film comes to a close, we are left where we began: on the eve of World War II and atop the Waterloo Bridge. As Roy stands at the mercy of the stars, holding her billiken in his hand and her memory in his heart, we are left with the image of a man who has seen it all; a man whose youth will forever elude him. Where you, dear reader, stand on the matter of ‘We accept the love we think we deserve’, I leave for you to decide. But, to you, Roy, I quote you Tennyson; as many a man must, remember this: “’Tis better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all”.

You may also like

A REMEMBRANCE OF THINGS PAST, PART II: APRIL

“I live with this movie every day of my life.” – Martin Scorsese Imagine

A LOVE FOR ALL TIME: FEBRUARY

“I don’t want you to go away. I just said that. You go if you want to. But hurry righ

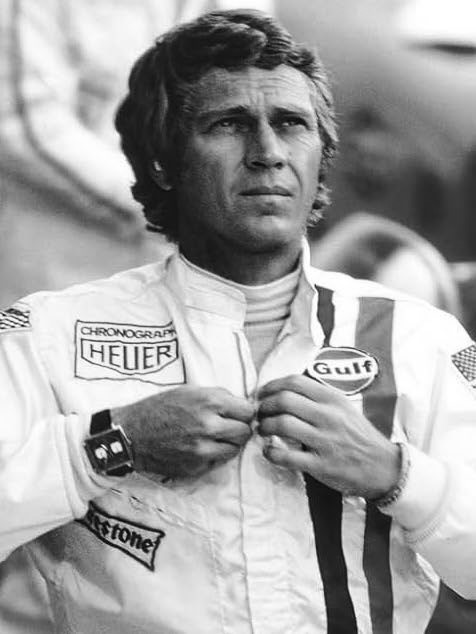

A MAN & HIS MACHINE: JANUARY

“When you’re racing, it’s life. Anything that happens before or after is just wa

Post a comment