A REMEMBRANCE OF THINGS PAST: MARCH

“We were the Leopards, the Lions, those who’ll take our place will be jackals, hyaenas; and the whole lot of us, Leopards, Lions, jackals and sheep, we’ll all go on thinking ourselves the salt of the earth.”

– Prince Don Fabrizio Salina

‘The Leopard’, based on Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s novel of the same name, chronicles the changes in Sicilian life and society during the Risorgimento. The Salinas are an aristocratic family, and the last bastion of a uniquely Sicilian breed; bred on pride, tradition, and a reluctance to roll over even in their slumber. But a wave is approaching, and its tidal, and it threatens not only to wake them, but to wash them away. It is through the eyes of the family’s patriarch, Prince Don Fabrizio Salina, that we will watch from the shores of the Mediterranean, looking, facing headlong into change. Even with his world on the brink of sinking, the Prince still favours his fortunes, his race against time; with the whole of history behind him, he clings closer to his destiny, and decides to take his chances.

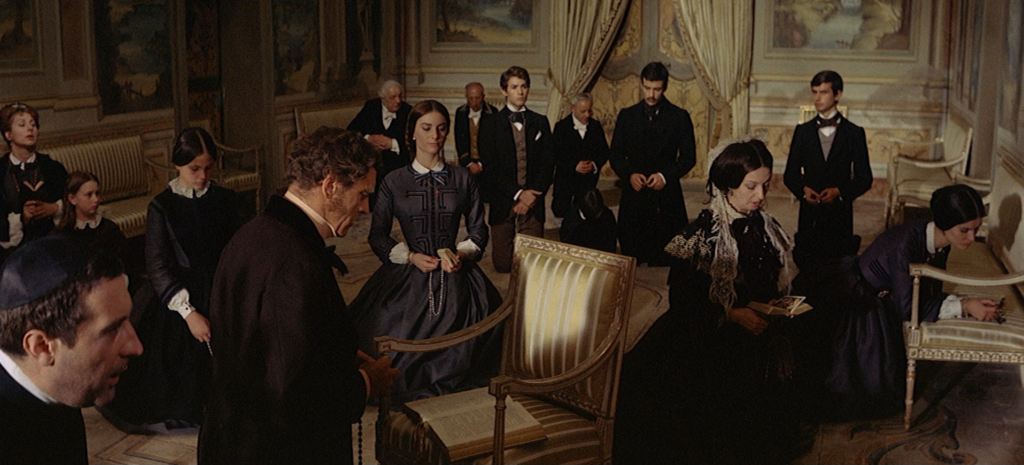

As we blow with the breeze through the balcony door, the film opens in the middle of an intimate Sunday prayer at the Salina palace. At home in the ornately decorated ‘palazzo’, perched among the sun stained hills of Sicily, we quickly see the Salinas as a family of formal proceedings, steeped in tradition and a rich antiquity. For them time seems to wait; imperative that nothing is rushed, that their heritage of order is resolutely maintained. Thus, when the mass is interrupted by the sounds of distant shooting, the echoed shouts of servants and the ringing of bells, Father Pirrone presses on with nervous hesitation, at the Prince’s insistence. But, with the hands of time beginning to weigh down on the curtain, he can no longer ignore the noise, and the Prince concedes to the intrusion. The dead body of a Neapolitan solider has been found in the garden, and with it, the short breeze that precedes a storm has reached their golden lawn.

The year is 1860, and our story takes place at the exact moment when Sicily comes into contact with the forward movement of history. Garibaldi’s thousand men have reached the island of Sicily (of which the aforementioned soldier was a victim) and, shortly, with a little help from the Prince’s nephew, Tancredi, Garibaldi and his redshirts will expatriate Sicily from the Bourbons. Soon enough, all signs will point towards annexation as part of a new kingdom – the new Kingdom of Italy. The Prince realises that with Sicily shed of its state sovereignty, he stands to lose the privilege and position in society afforded to families like his own. With the threat of land reforms that could follow the shaking up of social structures, the Prince foresees the rise of the middle class – the result of which will see the jackals and sheep overthrow the Prince’s own Lions and Leopards, and their way of life thrown out with them.

On the day of the Rosary, however, the Prince remains largely unconcerned. Thus, upon receiving a letter from a fellow nobleman, written with great concern and heeding greater warning of the rising tide, the Prince derides him for his cowardice. Unfettered by change, the Salinas continue with their life lived in no great hurry, and depart for Donnafugata, where their summer palace awaits. Knowing now what he will only learn later, we at once see the Leopard as a man who, for all his strength and majesty, may be no less naive, and possibly, even fallible.

Over the course of the films first act, the Prince grows increasingly aware of the need to reckon with his country’s changes. Throughout the second, he will begin to take the requisite steps before the ground can move out from under him. When a new national assembly calls for a referendum, the nationalists in win 512-0 in Donnafugata. In the wake of the new nation’s forward momentum, the Prince becomes acquainted with the town’s rich and influential mayor (the man responsible for the town’s questionable election results), and more importantly, the Salinas become acquainted with his daughter, Angelica.

Relatively uninspired by the children of his own, he sees in his nephew Tancredi, to whom he is a guardian, more of himself: a man of vitality, of ambition and enterprise. The Prince muses that a man like his nephew will do well in the new Italy – so long as he’s enough money and the right woman beside him. Thus begins Tancredi’s courtship of the beautiful Angelica, but more importantly, the Prince’s courtship of her father. Although the Prince might feel contemptuously towards the nauseating and obsequious mayor, he nevertheless recognises the betrayal of his integrity as necessary, for both his desires for his nephew, and for the future of his family. For the mayor, who has risen from rags in his quest for fame and fortune, the courtship is a most welcome one. Assuming that his daughters marital association with the House of Salina will buy him respect, and a seat at the table, he grasps greedily at the Prince’s proposal.

And so, with the Prince having broken bread with the jackals and sheep, having rerouted his family’s future back in line with the stars, having pushed through change so that, ultimately, things can stay the same, we reach the films final act.

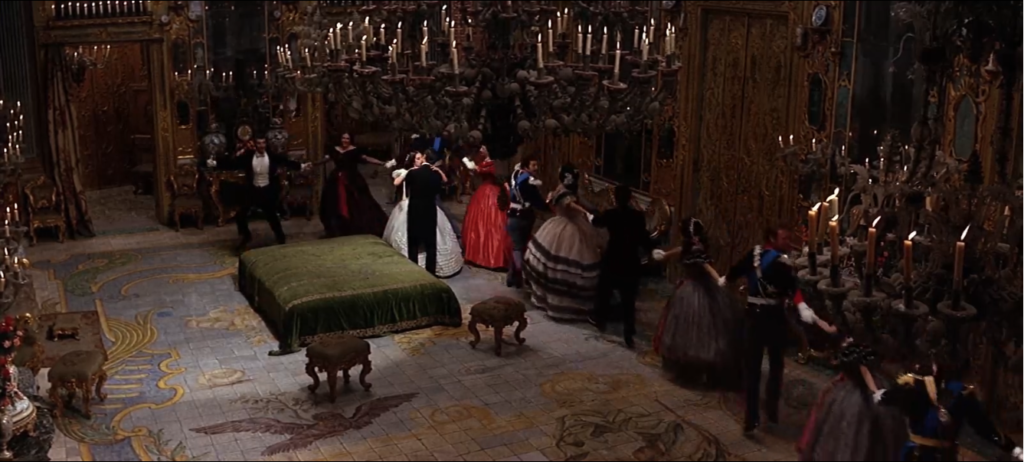

The last third of ‘The Leopard’ is a ballroom scene. It comprises all but the last few minutes of the films final hour, and is perhaps the greatest achievement in the history of film. Against the jubilation of an entire social order, we are left alone with the Prince, and the films central theme: man’s struggle between decay and mortality.

Upon arriving at the ball, the hosts tells excitedly of Colonel Pallavicino’s expected arrival. The Colonel, who shot Garibaldi (whose supporters have largely turned against him, Tancredi included) in the foot at Aspromonte, will be the talk of the town, and will fritter the night away charming the ladies with tall tales of his troubles. Waiting inside for the Salinas is Tancredi – in eager anticipation of his fiancé’s arrival, Angelica, for whom this marks a debut in high society – and in less eager anticipation of her father, the mayor, to whom an invitation has been begrudgingly extended. With the night set in its swing, the two arrive late, the mayor looking appropriate, if not inelegant; Angelica looking every bit any man’s dream, if not a little more so. Like a porcelain hand into a silk satin glove, she fits right in among the hostess and other ladies present, moving through the party with ease and grace. Even under the umbrella of his own name, the gap is closing between the Leopards, Lions, jackals and sheep.

Don Fabrizio makes his rounds and requisite greetings, but quickly becomes disenchanted in this scene of such extravagance, such foolishness in the face of their impending social death. Slipping into the party’s shadows as he wanders forlornly through a ceaseless cycle of rooms, each drowning in its decadence; through and endless parade of people, some drinking, others eating, some dancing, all celebrating; the Prince grows increasingly passive. For the first time in the picture, our focus shifts away from seeing his engagement with those and that around him, to seeing those and that through him. As Martin Scorsese says, “time itself [becomes] the protagonist”. The Prince withdraws, physically and spiritually, cloaking himself in his growing isolation.

At first, watching on, he assumes an air of reproach. The dissatisfaction with his counterpartal patriarchs reveals itself through nothing more than a concise cordiality. Among the women his age he sees some old flames, and resents squandering his best years in pursuing them. Looking into a room full of the younger women, trifling like schoolgirls and revelling in fatuity, the Prince fires from a safe distance, remarking, “these frequent marriages between cousins do not improve the stock”. But, later, with the night in full flight, the Prince finds himself far enough away to see himself in the picture. Superior though he may feel – certainly he seems it to us, evidently he seems it to him – these are his people. These are the only people with whom he can truly feel at ease. It is here, in surroundings such as these, with the people of this kind, that he is most at home. They represent the only life he’s ever known, the life he’s fought so desperately to keep and, judging by the way he’s treated, a world for which is the grand ambassador. But, though the earth keeps spinning, the Prince recognises its doing so as merely scientific. Though they mightn’t know it, this world, his world, is clinging on for dear life. Tomorrow: those dancing, those drinking, those delighting in brighter tomorrow and those not, the Lions and the Leopards themselves; we will all be relics living among the ruins. Time will wait for no one. And, thus, his mind moves from the party, to its people; disdain makes way for regret, and the Prince starts to reckon with his own mortality. What was the point of it all? What of everything he’s believed in? What’ll it mean when all this is over? As he takes stock of himself in the mirror, the Leopard seems to age in front of us. For the rest of the partygoers, it’s just another dusk till dawn; for us, a light dimming on an entire epoch; for the Prince, the sun setting on his own existence.

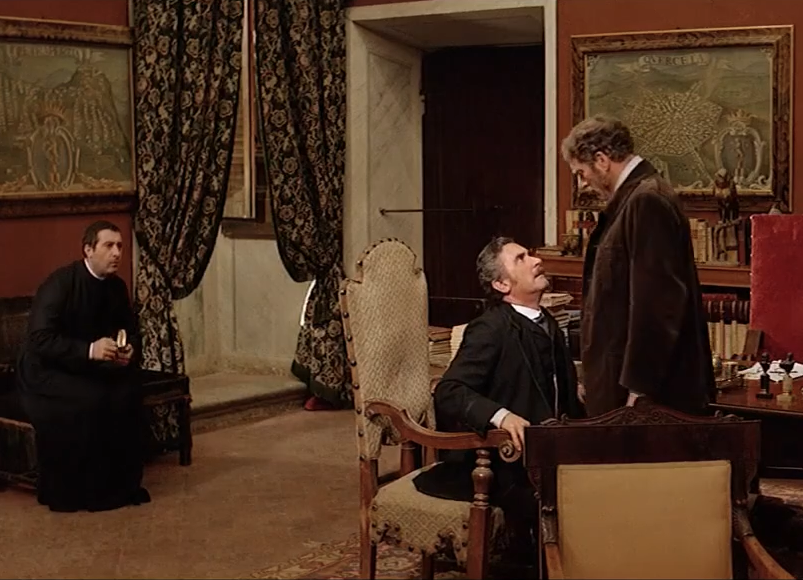

By the morning’s early hours, the Prince has resigned to defeat. As time’s antagonist he is utterly powerless. He retires to the library, seeking solace in a room which he presumes is little used. Hung on the wall is a copy of Greuze’s Death of the Just Man. Studying the Man upon his deathbed, the Prince wonders what the scene of his own death will look like. The thought calms him and, for a moment, resting back on the brown leather sofa his distress subsides – “was it perhaps because, when all was said and done, his own death would in the first place mean that of the whole world?”*

But the Prince is rescued from his conscience by the tireless Tancredi, and his Angelica, the latter of whom has come to ask the old man to dance. The two ‘joke’ of the Prince’s courtship with death, and the Prince is emboldened by their youth, for whom the party is just a party; for whom death is as as great an abstraction as the stars in the sky; the night is to be enjoyed for what it is, and the Prince accepts her request in the spirit of their exuberant ignorance.

The two join in the waltz and make a most prepossessing couple, his niece-to-be chattering warmly as they dance. The Prince’s attraction to Angelica is clear, so too is the reciprocation, and the weight of the world lightens on the Prince’s shoulders. There is an animal magnetism between them that must, and is resisted, but while the effect is equally as evident on both, Angelica’s clock faces forward, toward a future in which she can grow into the lady the Leopard makes her feel. But, for the Prince, the moment turns his clock back around. As the last dance draws to a close, the Prince notices that the rest of the couples have withdrawn from the floor. With the eyes of the ballroom and ‘the girl’ in his arms, the Prince revels in his brief respite from death.

The ball rolls well into the hours of the ungodly, with everyone feeling all the worse for it, but once one goes, they all go. Nothing if not a man of manner and decorum, the Prince leaves with party, but slips away from the family’s carriage and into the day’s dawn alone. Walking with his mind on his matter and an eye on a few surviving stars, he pauses for a passing priest en route to deliver last rites. After the priest enters into the house, the Prince looks up, with one knee on resting on the earth, and wonders when his time will come, when will he be allowed to join the stars, in an appointment far, far from all this. There’s nothing much he can do, and what’s more, if there was he’d be too tired to try. And so the night ends, and the film along with it, in the dimmest hour before dawn shadows, with little more than a sigh sent towards the moon. We see him for the last time as he disappears down the dark of an alley: a symbol of his country’s past, a past to which he feels he belongs.

* Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, Il Gattopardo, 1958.

You may also like

THE REBEL: PETER BOGDANOVICH

“There are no ‘old’ movies. Only movies you have already seen and ones you haven&#

A LOVE FOR ALL TIME: FEBRUARY

“I don’t want you to go away. I just said that. You go if you want to. But hurry righ

THE BIG SLEEP: PROGRAMME NOTE

“Nice state of affairs when a man has to indulge his vices by proxy.” Audiences attendi

Post a comment