THE TEN GREATEST FILMS: OF ALL TIME

“Film is like a battleground. There’s love, hate, action, violence, death… In one word: emotion”, said the writer-director Samuel Fuller. And right he was. If there was any criteria for choosing these films, it was two-fold: emotional impact and emotional durability. The former is self explanatory; by the latter I mean movies that continue to move me, perhaps increasingly so, and perhaps for different reasons, but continue to move me all the same, each and every time I watch them. These are the ten movies that, no matter where I am, how I am, even if I’m questioning who or why I am, never fail to stir something inside of me, and do so as reliably as the four glorious words, “I love you too”.

THE KILLERS

1946, dir. Robert Siodmak

Cinema is the Great Escape. Movies can take us where we daren’t ever go, could never dream of going, or are completely incapable of going. Where reality is dry, movies are drama, or as Hitchcock put it, “life with the dull bits cut out”. We can live out our fantasies, no matter how farfetched they may be, and for me, ‘The Killers’ is the embodiment of that. A quintessential film noir with deceit galore: everyone is out to get everyone, everyone else is out for the money, and only one man is out for the truth. Trench coats, guns, femme fatales, a world of shadows, smoke & mirrors, cigarettes that never go out, ‘The Killers’ checks all the marks of a life I can only ever dream of living. The plot, with all its twists and turns, is merely a hook on which the man coming in from the cold can hang his hat and coat on. His pistol stays by his side.

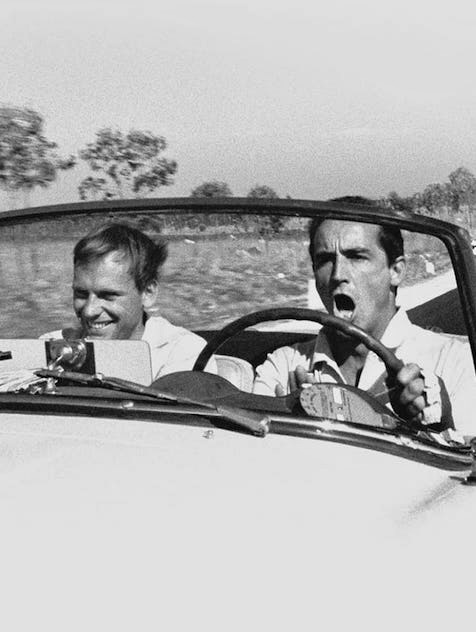

THEY LIVE BY NIGHT

1948, dir. Nicholas Ray

Nicholas Ray’s debut feature film is one that runs off with the familiar ‘lovers on the run’ trope, and finishes the race before the others have even heard the starting whistle. The bond between the two leads, Farley Granger’s ‘Bowie’, and Cathy O’Donnell’s ‘Keechie’, is one that strikes more than a chord in me every time. Ray shows us a relationship that is flawed, and not without its problems, but never has love between two people seemed so real, so necessary, nor so true. Though, since crime doesn’t pay, and contemporary censorship ensured that it didn’t, the driver here is not whether the two will make it out together, rather, just how long they have left in their loving embrace. Two wrongs will never make a right, but for their sake, I cross my fingers each and every time that maybe, just this once, maybe it will. Maybe you do only love once.

CASABLANCA

1942, dir. Michael Curtiz

What is there to say about a movie that surely makes everyone’s top ten list? Albeit a movie that unabashedly urges America to embroil itself in the greatest war in history, one that takes a man, his cafe, and the same man’s love for a married woman against the backdrop of the Second World War and dares transcend itself into one of the most viewed, most loved, and most quotes movies in history. Dooley Wilson and the piano, Humphrey Bogart and his bottle, Ingrid Bergman, Ingrid Bergman’s man, Sydney Greenstreet, Peter Lorre, Ingrid Bergman again, “Of all the gin joints, in all the towns”, “Here’s looking at you, kid”, “As time goes by”… Never has such an assured case been made. But it is curious that such a propagandist film continues to live on in the cultural consciousness with such force. If I had to take a stab at guessing the reason for its endurance, all-time great movie romances aside, I would aim for universality. ‘Casablanca’ is a world coloured with characters that we can all see ourselves in: realists, idealists, cynics, optimists, pragmatics, dreamers, winners, losers. In one way, shape or form, we are all there. Each and every one of us. For me personally… Well, “We’ll always have Paris”.

THE LIFE AND DEATH OF COLONEL BLIMP

1943, dir. Michael Powell (and Emeric Pressburger)

Powell and Pressburger’s (anti)war epic is an anomaly on this list. Regardless of whether I should or shouldn’t admit this, I shall: I have only ever seen this film once. I am not someone who thinks much about a movie after I leave the cinema – I tend to think about me. How did it make me feel then, how do I feel now, what made me feel that way, what did I like, what did I not like, etc. I rarely place myself in the shoes of the characters, question their motives, or wonder what I would have done if I were them. But for one reason or another, ‘The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp’ has played in my mind continuously, for the duration of the year since I saw it. It touches on such a variety of themes, ruminates so tenderly on the human condition, that it has proved impossible for me to put the proverbial book down. ‘Blimp’s’ is a life filled with struggles, struggles so universal that, whichever way I choose to turn, or turn away from, I find myself facing his way again.

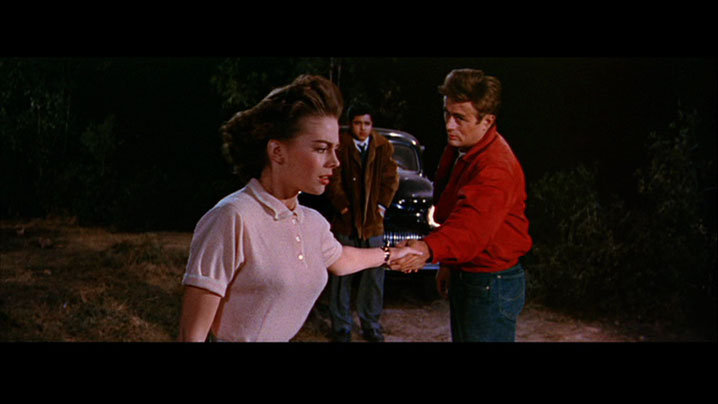

Rebel Without A Cause

1955, dir. Nicholas Ray

Like most people, when I first came to ‘Rebel’, I came for James Dean. And while his is an undeniably superb performance, one that helped shift the paradigm of acting and sent Dean stardom’s way, I see it now as the definitive Nicholas Ray performance. By the turn of the fifties, Ray had hit his stride, & more and more his films resembled his own vision of the world – one that was not only dim but dimming, though somewhere, a way through the clouds, glimpses of paradise were always somewhere in sight. Ray batting at his best is an entirely unique cinematic experience, one that is as much theatric, and operatic, as it is of the cinema. No matter how many rolls of the dice his characters have left, one can’t help but feel that the stakes couldn’t possibly get any higher, and ‘Rebel’ represents this particular mountain’s pinnacle. The betrayal of Sal Mineo’s surrogate parents, in James Dean and Natalie Wood, climaxing at the doors of the Griffith Observatory, as dawn begins to break, when the gun is fired, followed by Dean’s horrified screams, “I got the bullets!”, remains one of the medium’s most moving closes.

The Third Man

1949, dir. Carol Reed

‘The Third Man’ is a peculiar film. It is in essence a mystery, possibly a thriller, though you’re never quite sure who you’re supposed to root for. You have no idea who’s right or who’s wrong, nor who’s in the right nor in the wrong. In actuality the hook upon which the plot is hung, is merely a hook. And if the plot is Holly Martins’ drab herringbone overcoat, then hidden beneath it is the most beautiful silk scarf you’ve ever seen. One is left with very little reason for optimism when the final credits roll while Martins stands, watching, as the girl he’s fallen in love with walks right past him, but while ‘The Third Man’ is melancholy, and cynical, it is too simultaneously so very beautiful and so very poetic, that its conclusion feels almost counter intuitive to its intentions. Who was this Harry Lime? Can his girl ever love anyone else? Are the police right about him? Is he better off dead? Is he even dead? In a tale of friendship, betrayal, love and loyalty, never has a plot mattered less and while we’re at it, never has Vienna looked so sumptuously good.

Brief Encounter

1945, dir. David Lean

There is something about passion raging inside two people that identify with neither the words passion, nor raging, that is both wholly comforting and perpetually fascinating. Lean’s British classic, based on the Noël Coward play, remains just that – an undeniable classic. Though, on the surface, it is the movie on this list that has aged the most; upper lips are still stiff, unhappy marriages are unthinkable, even the expression of an emotion as universally loved as love seems taboo. And the two characters fighting against their emotions, waging war against their desires, are two of the most decent, decorous leads that the screen’s ever seen. What chance do they have? By employing films’ most imitated use of the flashback, Lean lets us know from the jump that their chances are none. Sometimes we can’t have the love we deserve. Sometimes we have to let go. Sometimes it really isn’t meant to be. These are pills that we all have to swallow at least once or twice in our miserable lives and, apparently, ‘Brief Encounter’ helps me wash them down.

Singin’ in the Rain

1952, dir. Stanley Donen

The fifties were undoubtedly the musical’s greatest decade, and ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ is undoubtedly cinema’s greatest musical. A tale of love at the time when movies were transitioning from silence to sound, Hollywood gave us a rose-tinted, tongue in cheek look at itself in the mirror. Now, as far as movie genres are concerned, musicals are, to me, the most native cinematic genre. The boxes that make cinema the greatest medium, are boxes inherently ticked by the greatest musicals. And ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ has a surplus of ticked boxes. Nevermind the titular song and dance number, after Gene Kelly finally kisses Debbie Reynolds, which remains, without a doubt, the single most joyous moment in the history of movies. While no other film on this list I would call particularly joyful, the sheer happiness of Stanley Donen’s musical masterpiece is simply infectious, and no matter how hard I try, I am susceptible to its delight every time.

They All Laughed

1981, dir. Peter Bogdanovich

Peter Bogdanovich’s early eighties romantic-comedy follows a group of three private eyes who all fall hopelessly in love with the women they’re supposed to be private-eyeing. As far as movies premises go, that has to be up there with the best of them. In my mind, it might even sit atop the pile. And dare I say that Bogdanovich delivers on his premise. While both sunny and heart warming (a ‘feel good’ movie if ever there was one), Bogdanovich’s movie simultaneously smoulders with a gentle melancholy and beautiful sadness that makes ‘They All Laughed’, one of the truly hidden gems of cinema, and one of the most personal movies I’ve ever seen. ‘Some of them promised they’d never fall in love’, reads the posters’ tagline. And some promises were meant to be broken.

[Not to reflect any of the above adjectives back onto myself, but ‘They All Laughed’ serves a secondary function in my life – that of a barometer against which I measure friends and loved ones. Love this movie, and perhaps, you might love me. Don’t, and I could never love someone without a heart anyway.]

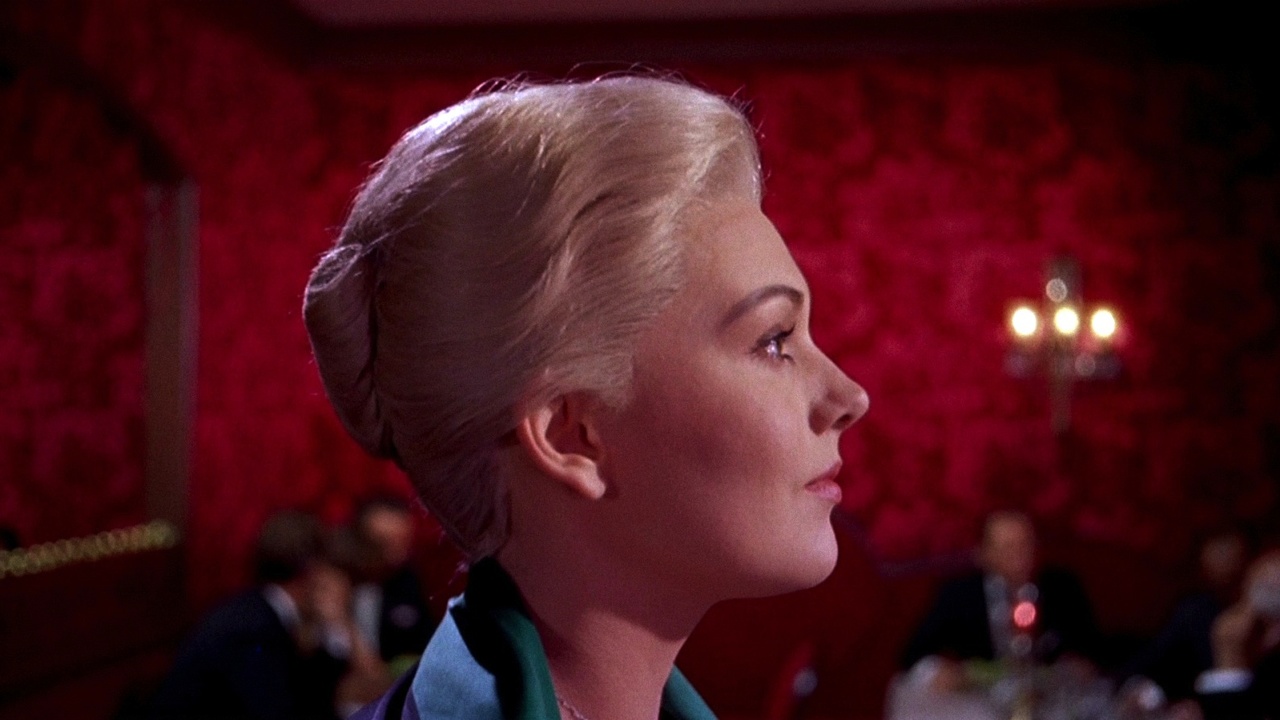

VERTIGO

1958, dir. Alfred Hitchcock

Alfred Hitchcock, not known for being laconic, once summed up his defining masterpiece, cinema’s defining masterpiece, as, “boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy meets girl again, boy loses girl again”. While his summation is, of course, not inaccurate, it is indeed comically inadequate. Perhaps his sparsity of words was due to the fact that, contemporaneously, ‘Vertigo‘ was both a critical and commercial flop, and to try sell its story in a press release was clearly an exercise in futility. Or perhaps he was quietly having a wink at us all, knowing that one day, years down the line, its themes would be unpacked and attacked, that one day his movie would receive the medium’s greatest reassessment and subsequent critical reversal. Who knows. Plot wise, however, the general consensus is that ‘Vertigo’ has more holes in it than your favourite Swiss cheese. Scottie (James Stewart) is persuaded out of retirement by an old college friend, whose wife Madeleine, Scottie is to follow. For several scenes, set solely to diegetic sounds and Bernard Herrmann’s spellbinding score, Scottie trails her, following Madeleine into flower shops, museums, cemeteries, old hotels, and finally into the San Francisco Bay. The two begin to meet in more mutual circumstances, and Scottie finds himself smitten. What he does not know is that Madeleine, or who he thinks is Madeleine, is merely a rouse. Though, when “boy loses girl”, we are as unaware of this as Scottie is. Then, with Scottie believing to have lost Madeleine for good, the story switches focus. It is here, with the revealing of the rouse, as Scottie grieves the loss of the woman he loved, that he meets someone who reminds him of her. It is also here, with what would typically be the climax behind us, that ‘Vertigo’ takes a different trajectory, propelling it out of the mystery\thriller category, and into a league of its own. Hitchcock’s forty-fifth film is one that veered away from his usual formula, which probably explains why it disappointed both critics and audiences alike. The result can be classed neither as a suspense, nor really a ‘mystery’, but in the way that it deals with love, desire, and obsession, it is hypnotic, and terrifyingly so.

One morning, five springs ago, as I lay on a Los Angelan floor feeling unenthused about the idea of traipsing around all day without a car again, I decided to give Alfred Hitchcock a go. ‘North by Northwest’ was first, since Cary Grant’s was a name I knew. With the movie behind me by breakfast, I decided to swap the sun for shadows, and to continue my journey. Following swiftly on its heels came ‘Psycho’, ‘Rear Window’, and ‘To Catch a Thief’ . Then I watched ‘Vertigo’. Expecting what I had come quickly to understand as the Hitchcock ‘genre’, the credits rolled, and I felt not only underwhelmed, but disappointed. I found it at best, unlikeable, at worst, really rather boring – two claims one can hardly levy against Hitchcock’s films. I wasn’t aware then of its standing atop the 2012 poll as the greatest film of all time, nor was I aware of the endless library of books, articles, essays and films about it. It was merely another one ticked off the list, one I didn’t quite connect with. But since then I have changed; grown in some ways, regressed in others. I have found love a few times and lost it just as many, made new friends and grown apart from old ones, done things I didn’t think I would’ve and not done things I should’ve. As I grow and get older, above all the rest, ‘Vertigo‘ seems to grow with me. The more I know, the greater my capacity to empathise with certain feelings, deal with certain emotions, the more the movie seems to show itself to me. It reveals new depths and new layers I was not yet ready for on that uncomfortable, dust ridden Californian floor. Scottie’s, in this case fulfilled, desire to recreate, inch by inch, exactly what he has lost, is not something I can directly relate to. But that feeling of emptiness, and the desire to fill it, even in some cases the feeble attempt to replicate that which once filled it, is something I think we are all too familiar with – regardless of whether that which eludes us was ever real in the first place, or purely an image we’d created. In that sense, Scottie reflects the dark side in all of us. His actions embody a universally deep desire to fill a void that has been left by someone, to heal ourselves, no matter the pain it might cause, no matter the cost. He merely takes it a step further than most of us’d dare to. It was only upon my fifth viewing, two years later, that I felt like I finally understood it. But I was wrong. The number of times I’ve seen it now has since surpassed single digits, and every time I find myself grappling with new feelings, new reflections, and new emotions. ‘Vertigo’ remains, in my opinion, the greatest film ever made.

You may also like

The Art of the Dissolve

Tellus integer feugiat scelerisque varius. Sit amet volutpat consequat mauris nunc congue nisi. At u

A ROAD OF NO RETURN: MAY

In life, it often is said, there’re two types of people. On the one hand,

A GANGSTER’S PARADISE: JUNE

“A cartoonist’s only commandment should be: Thou shalt not bore.” – Tex Aver

Post a comment