A TALE AS OLD AS TIME: JULY

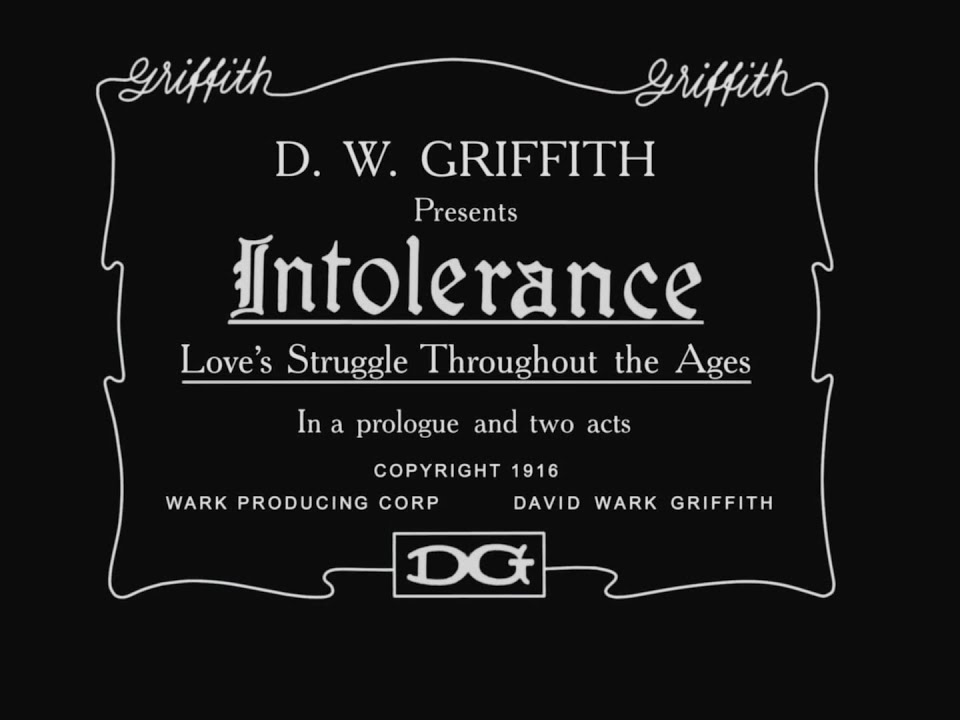

‘Intolerance: Love’s Struggle Through the Ages’ has long been a white whale of mine when it comes to silent Hollywood cinema. D. W. Griffiths’ momentous historical epic, one of the earliest examples we still have preserved, holds a truly significant place in the early years of Hollywood. Famed for both its daring narrative innovations and monumental scale, there simply weren’t many films that had looked or felt like this prior to its release. To me, it always seemed lofty, grandiose, potentially inaccessible. Having finally sat through its near-three hour runtime, I can now safely see why it has earned such a reputation in the first place. Though not personally the best work of silent Hollywood I’ve ever seen, it still managed to impress and excite me in thrilling ways, more than a century on from its initial creation.

Exploring the relationship between love and hate across hundreds of years, Griffiths uses four separate but similar narratives to make his broader, admittedly fairly vague, point about the eternally duelling human emotions. They are emotions that are the bedrock of so many works of art throughout history, so it feels fitting that they helped define cinema in its early stages too. He jumps back and forth between all four timelines from the off; one set at the fall of Ancient Babylon, one following Jesus’ life and teachings in the build up to his crucifixion, one following the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in 16th Century France, and one in the contemporary day exploring a young couple wrongly and constantly beaten down by society. These interwoven timelines seem especially groundbreaking when seen through a modern lens, where non-linear, multipronged narratives are a much more commonplace in the mainstream cinematic language. The editing between them all is relatively smooth, especially so given the era the film was made in and the relative infancy of long-form storytelling in film at that point. Aided by detailed title cards, you rarely lose track of any one thread, and some slightly uneven moments are more than forgivable given Griffiths was essentially creating non-linear storytelling in real time. This editing really comes to fruition in the thrilling final third, as all four reach their highly melodramatic conclusions in near-perfect unison.

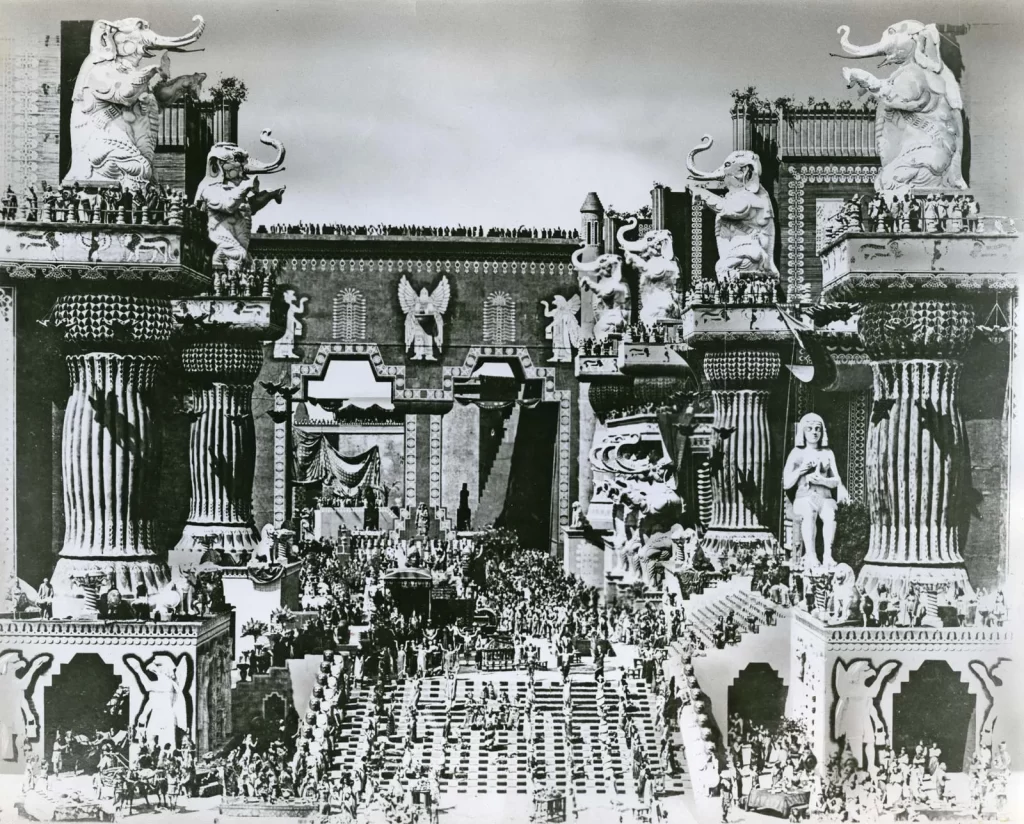

From a production perspective, Intolerance is also monumentally impressive. Recreating various different historical eras, each one captures the essence of its time period well (or at least the atmosphere Griffiths wanted to convey about said time period). Be it the stripped-down, washed-out reality of the early 20th Century in the modern sequences, the intricate details of 16th Century France, or the gaudy opulence of ancient Babylon, you totally buy into the lavish design work, historical and contemporary alike. This is particularly palpable in the immensity of the Babylon sequences, which are rightfully what the film is most remembered for to this day (the remaining sets became brief Hollywood landmarks in the subsequent years before their eventual demolition). The sheer size of the city walls as enormous battles rage around these sets are almost breathtaking. Griffiths filled his frames with striking compositions that still have the power to amaze. To see a film of such scale, at such an early point in cinema’s lifespan, is a sobering reminder that advancement doesn’t always equal improvement.

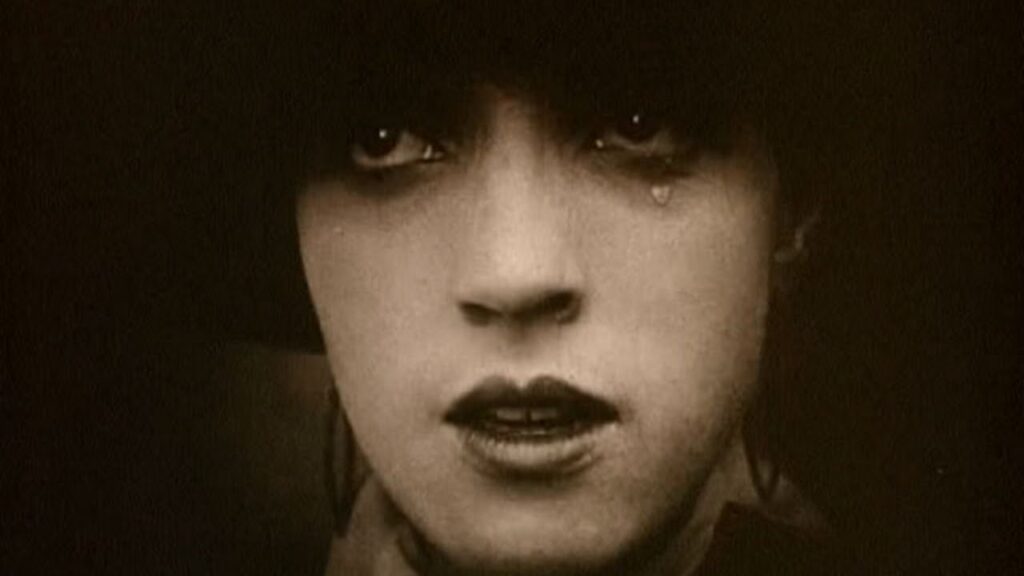

All that being said, Intolerance is far from perfect. Narratively, the Babylon and modern day sequences are significantly more fleshed out and engrossing than the ones set in France and Nazareth. The sequences involving Jesus are particularly uninspiring, perhaps given how overdone that particular story feels in Hollywood (Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ being the best and most prominent example in silent cinema, almost a decade on from this). Though all the storylines crescendo smoothly around each other during that final third, the latter two are a bit of an afterthought during the first two thirds of the runtime. The thematic links between each story don’t feel quite as obvious and powerful as Griffiths perhaps intended either. His title cards talk of love and intolerance in the very general sense, which in turn results in a pretty tenuous deeper meaning. Often I found myself searching for the connections, rather than feeling them naturally. It’s still a pleasure to take in, but it lacks an emotional core to heighten everything.

Also, the film’s entire message – the focal point of the whole epic creation – is born out of such idiotic and racist ideals that, if you are aware of them, makes it hard to totally emotionally invest in the narrative anyway. Griffiths was so perturbed by negative reactions to the racism of The Birth of a Nation, racism that was undeniable and challenged even upon initial release, that he decided to make this in response. It served as his proof that it was in fact his critics who were the intolerant ones, and a rallying cry against censorship in film production. And while not overtly racist itself, unlike his previous film, the depth of Intolerance is about as palpable and fleshed out as such an idiotic foundation would suggest. For all its grandeur and innovation, it never quite escapes the shallow, myopic nature of its nucleus.

Technically speaking it’s still a marvel, influencing swathes of filmmakers for generations, notably early Soviet directors, who marvelled at the editing and in turn pioneered cinematic techniques that are as relevant today as they were in the 1920s. It’s also, despite my reservations, an entertaining watch – a film brimming with boundless creativity from an era when artists were still attempting to discover their limits. There is perhaps no better proof that sometimes art and artist can (and should) be separated enough to explore and appreciate true film history.

If you would like to read more of Euan’s thoughts on the subject of cinema, you can find an endless array of articles touching on topics from the politics of Alex Garland’s ‘Civil War’ (whatever that is), to a celebration of ‘The Life and Films of Ginger Rogers’ – all of which can be found on his substack: https://euanharris.substack.com.

You may also like

A MAN & HIS MACHINE: JANUARY

“When you’re racing, it’s life. Anything that happens before or after is just wa

A LONG LOST LOVE: AUGUST

“A boy’s will is the wind’s will, And the thoughts of youth are long, long thought

A REMEMBRANCE OF THINGS PAST: MARCH

“We were the Leopards, the Lions, those who’ll take our place will be jackals, hyaenas;

Post a comment