A GANGSTER’S PARADISE: JUNE

“A cartoonist’s only commandment should be: Thou shalt not bore.”

– Tex Avery

I’ve long felt the same way about short films as I do about shorts. The existence of each is entirely utilitarian, and since the invention of the trouser, and that of the feature film, we’ve come to recognise the inferiority of their shorter length counterparts. There’s no doubt that, at best, they’re lesser variations on the form; at worst, they are lesser forms entirely. Since the decision to go short is a service only to ourselves, and a disservice to others, it ought be subject to severe scrutiny. However, where shorts might just be justifiable on a day as hot as the torched top of a crème brûlée, short films too are of a certain utility to the impoverished movie-maker not yet within reach of ninety-minute magic. That is to say, neither are entirely without merit. And, while my feelings towards shorts shan’t be subject to change at any time soon, for reasons I daren’t and caren’t to admit, I decided this year to re-evaluate my feelings towards the short film, and committed to watching one a day before a feature. Naturally, I began by looking backwards.

Contrary to the general consensus, comedies have dated the least in the last hundred years of Hollywood movie-making. Furthermore, since I would be watching these in the mornings, comedy seemed the perfect fit. And so I did what any sane person should, and began with Buster. If a jar of jam lasts seven sittings, then by jam-jar number two I’d already run through all the Great Stone Face shorts that I could find online. And they were great (‘Cops’ being the greatest of all). I moved quickly onto Chaplin, but quickly back again, since his early attempts turned out to be no match at all for the features that would follow. A couple of Harold Lloyd’s later and I was onto Laurel and Hardy, who turned out not to be the duo for me. Though Keaton had kicked things off so well, I was quickly losing faith. I tried a couple of dramas and found them a little overdone to go well with my breakfast. I even watched some of Hollywood’s Second World War propaganda shorts, but they weren’t so suitable as early morning material. I even tried switching to cereal, but I found no answers at the bottom of that box. Still, as a great man once said, ‘disillusionment is a disease’, and so I set about finding a remedy. Where I found it, was in the least likely of places.

I’d always thought of cartoons as a by-product of the studio era; animated shorts that were made solely for screening at the front end of a feature. As fate would have it, the world of animation was far, far greater than that. Of the ‘big five’ studios in Hollywood’s heyday, all five produced cartoons; two of them (Warners and MGM) even set up entirely autonomous production units for their creation, and they were, of course, Disney’s bread and butter for the best part of a century. But I would learn that later on, and with winter encroaching on Spring, with no knowledge at all and no way to navigate this rabbit hole of ten-minute movies, I began with the one thing I knew. And, as is often the case, what I knew was the name of a chap. That chap was Chuck Jones. When I say that I ‘knew’ Chuck Jones, all I actually knew was the name, and its association with animation. And, so it began.

The old cartoons are riotously funny, remarkably sophisticated, and wholly original. Much like the movies of the time, they reach to the young and the old, to the smart and the silly, and do so without ever pandering to either side of any spectrum. As I dove down deeper and darker into the world of animation, stacking up films on my Letterboxd tally (there, the cat’s out the bag), reading reviews and respecting random users recommendations, one name began to crop up over and over, and again and again, and soon I was seeing it on the back of my eyelids when catching forty winks. That name was Tex Avery.

Animation has been around as long as movies themselves. The earliest attempts at cartoons were, in fact, photographs of drawings that appeared to move when projected as high speeds. But, unlike the pictures, animation was a much slower moving machine, and it took a little longer for the technology to catch up with the artists’ imagination. After revelling in relative crudity until the early teens, it wasn’t until the end of the 10’s that animation started to resemble the sort we see today. In 1919, with the invention of Felix the Cat, the first hand-drawn star was born. In the 1920’s, with the invention of synchronised sound and the founding of Walt Disney’s studio, animation took its first big leap. For the remainder of the twenties, Disney did what Disney does, and cornered the market (they even bought exclusive rights to Technicolor, which they held until 1935). By the time of the Great Depression, Disney’s cartoons, with all their cute and cuddly characters, their picture-perfect backgrounds and their saccharine sentimentality, had become the industry standard. And then, in 1935, along came Tex Avery, and suddenly a carrot munching bunny named Bugs was shoving a shotgun down Elmer Fudd’s throat. The same way that Griffith had come along thirty years earlier and showed the world what a movie could be, and would be henceforth, Avery wangled his way onto the Warner Brothers’ Lot and rewrote the next ninety years of animation. By the turn of the thirties, Avery’s fingerprint could be seen all over cartoons, with “characters leap[ing] out of the end credits, loudly object[ing] to the plot of the cartoon they were starring in, or speak[ing] directly to the audience”. Like Jean-Luc did with film a quarter century later, Avery dismantled the cartoon, and redefined the form in the process of putting it together again.

But, as much as he is revered for rewriting the rules of mainstream animation, what makes his cartoons as fresh today as they will be tomorrow is his unwavering commitment to the gag. To Tex, there was everything else, and then there was the gag, and it wasn’t the everything else that came first. Fast and furious is how he served them, and his eight or nine-minute movies were essentially excuses to exhibit an inexhaustible amount of jokes. And, since all comedy revolves around the subversion of audience expectation, it was in parodies that he found the most fertile ground. ‘Travelogues’ became a common fixture in Avery’s oeuvre; even the fairy tale, a market which Disney dominated, was appropriated by Tex. Anything that required as little set-up for the audience as possible provided the perfect target for Tex to take aim at. It seems obvious, therefore, given that ‘motion’ and ‘pictures’ were the words on everyone’s lips at the time of the Great Depression, that Avery would soon set his sight on Hollywood, and on movie-making itself. And in the years post-prohibition, there was nothing more familiar to audiences, than the gangster genre.

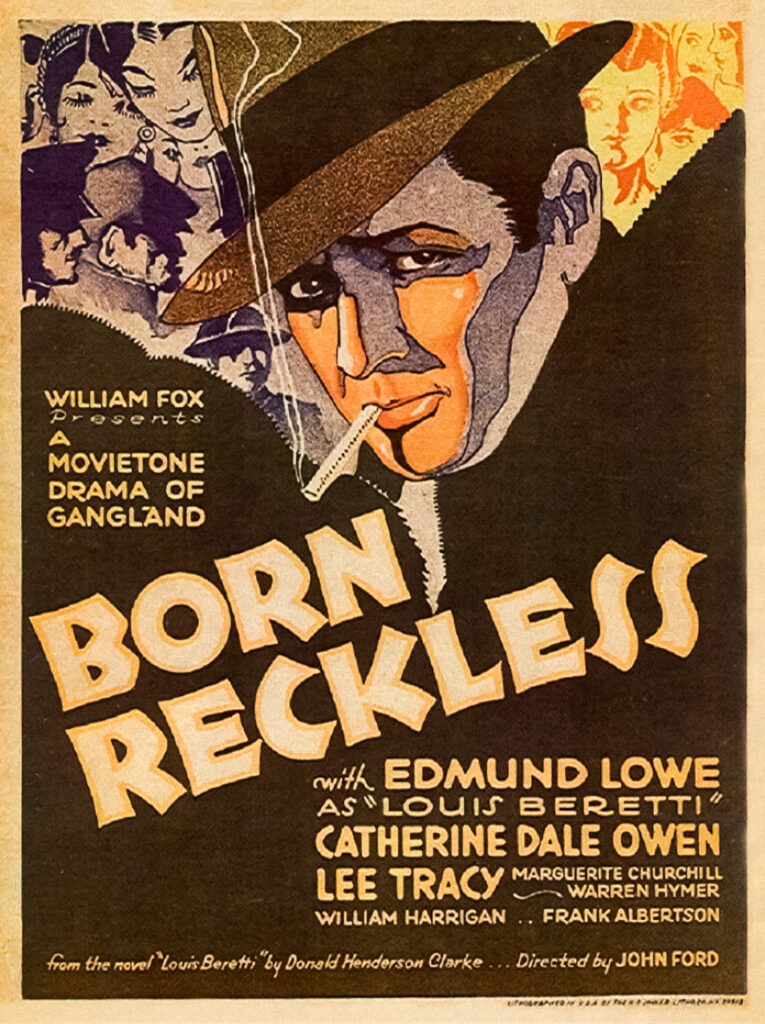

In our minds we might remember the 1930’s for the fall out from Wall Street or the end of the Prohibition; in our hearts, however, we surely remember it for the Hollywood gangster movie. At a time when it looked like the world was hurtling towards irreparable doom, cinema provided the ultimate escape, and cinemania reached its absolute apex. And, of all the genres that were thrown around in the early sound era, it was the gangster story that stuck. With its socially conscious storylines and its sympathetic view towards working class struggles, it provided audiences with the comfort they sought throughout the hardship. Equally, though, with its thrilling action sequences, its gangster-as-celebrity characters and their glamorous degeneracy, it supplied cinema-goers with a much needed escape. With the release of ‘Little Caesar’ in 1931, the Warners Brothers struck upon a gold mine. They followed it up with ‘The Public Enemy’ in the very same year, and with it, the gangster genre was born. Soon, Warners shorted all their stock on the gangster flick, and with the real-life gangsters becoming real-life celebrities, the gamble paid off in spades. (Gangsters and gangster stories became such a popular cultural phenomenon that the real life tough guys publicly praised the movies that were based on them; John Dillinger was even shot coming out of the cinema, having just seen a gangster movie.) All the majors got involved, and even though such notables as ‘City Streets’ and ‘Scarface’ were the products of other studios, Warners had something that none of them did: the gangster actors. With Edward G. Robinson, James Cagney and Humphrey Bogart all under contract ate the studio, the world was, as Scarface would have it, theirs. Then, in 1938, at the height of movie-goers gangster mania, the studio released ‘Angels with Dirty Faces’ to huge box office success and (almost) universal critical acclaim. And so, with rags-to-riches racketeers in every paper and on every screen, the stage was all set for Tex to throw his hat into the ring. And throw it he did, in his inimitably screwy way, with a cartoon that came out the following year, titled ‘Thugs with Dirty Mugs’.

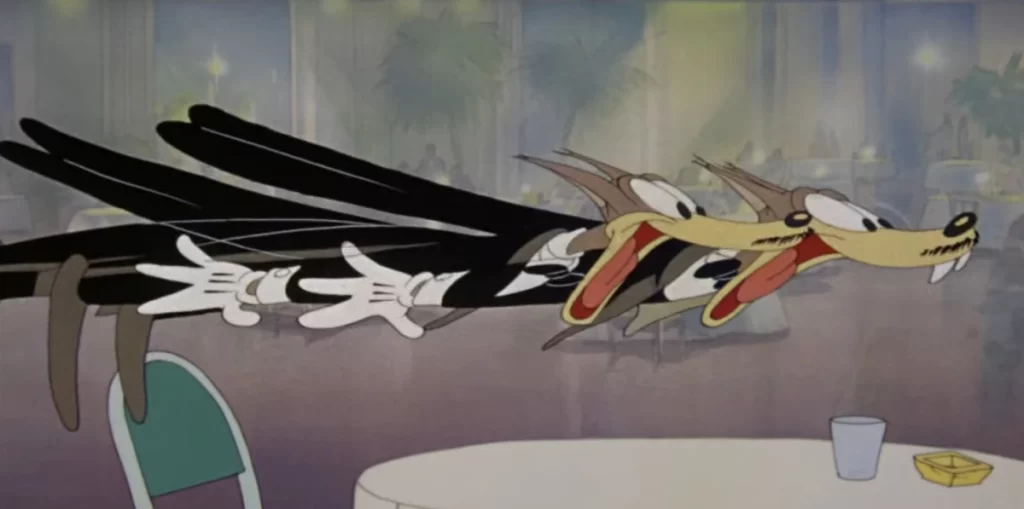

‘Thugs’, starring ‘Ed. G. Robemsome’ as the gangster ‘Killer Diller’ (who has a proclivity to say ‘see’ after every other sentence, as per the real Edward G. Robinson), is as much a reflection of movie-goers and movie-makers, as it is just the funniest cartoon of them all. In fact, its claim to the latter hinges almost entirely on the former, and Avery makes the most of the fact that we all know what’s going to happen (and I’ll make the most of it too, by not writing about it). He knows, that we know, that a gangster will rise, and a gangster will fall, and part of the parody is pointing out that the tropes of the genre are so deeply embedded into the public consciousness that we can follow a features worth of story in under eight minutes. Yet, Tex did what Tex does best, and still somehow finds a way to surprise us. By taking the basic ‘black-out gag’ structure, whereby scenes begin without any set-up, and end without any real resolution, Tex ties together a series of disconnect scenes that provide the perfect excuse for him to plow his way through an endless parade of sight gags and spot jokes. The result is a preposterously funny and ‘thrilling meta-narrative’ game that highlights the sheer ludicrousness of Hollywood’s favourite, and most native genre.

Part of the fun is that the joke is on us, the audience, for eating up all these formulaic gangster flicks. Even the cartoon itself knows how ridiculous it is for parodying it, and when ‘Killer’ interrupts the planning of the mob’s next job by breaking the fourth wall and speaking directly to us because he’s so proud of his Fred Allen impression, and winds up annoying his henchmen by “showing off” with it, we realise that everyone, including Tex himself (who voiced both Killer Diller and Killer’s impression of Fred Allen), is the butt of the joke. And, as though that wasn’t enough, Avery manages to squeeze in the most inventive, and organic use of ‘guy in the third row talks back to the cartoon’ joke which, now a mainstay of animated movies, was his very own invention.

But, as funny as it is, and it is delightfully so, what makes ‘Thugs’ so special, and raises it above pure parody, is that, for all its fearlessly dumb jokes, it reveals itself as an honest entry into the thirties gangster canon. It has heists, during one of which Killer’s guns hover in the air while he uses his hands to snatch the money, it features the first star-gangster-actor (or at least a brilliantly realised cartoon caricature of him); it’s got classic mob hideouts with names like ‘Skunky Joe’s Beer Joint’, and it’s even got an earnest attempt at showing how gangsters were celebrated in certain sectors of honest society. The film even employs the use of montage, and its reliance on newspaper headlines to tell the story show Avery’s awareness of the stylistic flourishes that were woven indelibly into the gangster genre. As happy as it is being just a cartoon, the films reflexivity and satirical stance on the relationship between a screen and its audience, elevate ‘Thugs’ to an almost unprecedented status for an animated short film.

To talk about the jokes: why I think they’re funny or how I think they work, would be to spoil the pleasure of watching it yourself. And, since it runs a few seconds shy of eight minutes in length, you’ve really no reason not to. (If you do, listen out for the line “take that you rat”, which is the set-up for what is probably my favourite joke ever written.) How one man packed so many punchlines and so many punches into such a short cartoon, I will never know. How he managed to imbue the very same cartoon with such depth, and turn a series of gags into a culturally important artefact, is beyond comprehension. That he made that cartoon about the greatest era in cinema, and used it to take a look at my favourite era in history… Well, he’s clearly a man after my heart.

1 Comment

Post a comment Cancel reply

You may also like

The Greatest Shot in Film

Preface What is the greatest shot in film? Aside from being a hard question with an ea

The French Dispatch

Tellus integer feugiat scelerisque varius. Sit amet volutpat consequat mauris nunc congue nisi. At u

A LONG LOST LOVE: AUGUST

“A boy’s will is the wind’s will, And the thoughts of youth are long, long thought

Johnny Bilbao

Wonderful article, sir