A ROAD OF NO RETURN: MAY

In life, it often is said, there’re two types of people. On the one hand, there are those that wake up everyday just to throw open the windows and let in ‘la vie en rose’, and then on the other hand there’re those that don’t. Or, at least so said a one Ms. Audrey Hepburn in ‘Sabrina’. Now, if you’d have asked her one time co-star of a very different movie, George Peppard, he would’ve told you (as he did Ms. Hepburn), that in fact there’re those who can stick out their chin and say “Okay, life’s a fact”, and then there’re those who are just too afraid to make any such declaration. If you ask me, however, I’d argue that the two types are more tangibly defined than all that. Where, over here you have a group, Group A, characterised by their empathy, their humanity, and their willingness to abide by the golden rule; over there you have the other group, Group B, who can be discerned by their decision to inflict their bare legs onto others, in public, by wearing shorts on an airplane. But, whatever it is and whoever it was that said it, whether the sentiment is about this or whether it’s about that, one thing is surely true: in life there are two types of people – there’re those who do, and those who don’t. Dino Risi’s early sixties comedy-drama, ‘Il Sorpasso’, is a movie about just that discrepancy, and the dynamic we find between two men who find themselves at opposing ends of the scale.

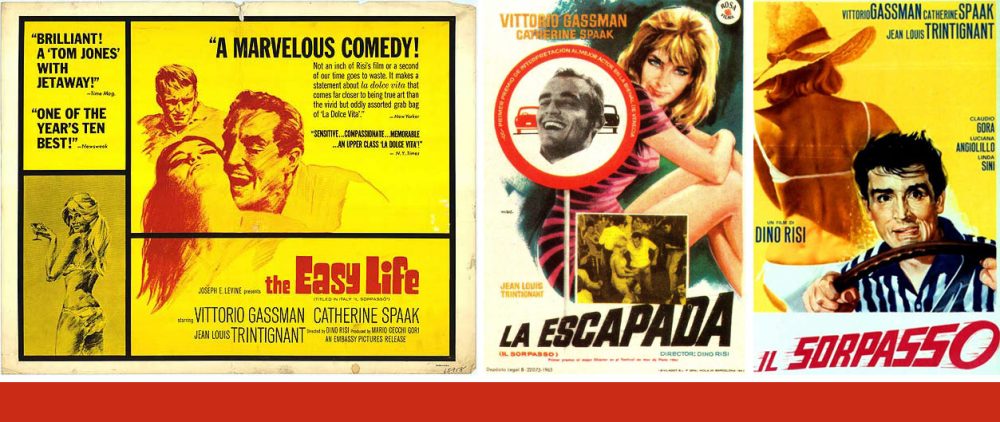

The film’s title refers to the Italian custom of overtaking cars on the highway and, as the name would suggest, ‘Il Sorpasso’ takes place largely on the road. But, really, the title is a metaphor for an approach to life, a ‘celebration’ of wanting, and doing; of overtaking that which stands in the way and not worrying about the traffic coming in the opposite direction.

The film opens on a sun-baked and deserted Rome. It is a national holiday, and the first of our two leads, Roberto (Jean-Louis Trintignant), is spending it inside, studying for his law exams. Roberto is one half of the masculine Italian identity – the pious half – as innocent as he is pure, and as meek as he is careful. Looking out from the window of his apartment, he sees a man of roughly his age drinking from a fountain on the side of the road; a man a little taller, broader, and bolder. The other man is, of course, the surpasser, Bruno, the descendant of the Roman warrior – the other half of the masculine identity. Before long, Bruno will ask himself up to Roberto’s flat to make a phone call (about which Roberto is hesitant), and not long after that, the two will find themselves on the road, together, for the duration of their nation’s holiday (about which Roberto is more than hesitant). A myriad of adventures unfold and, in the process, Roberto is opened up to a completely different way of life – one that he feels very much at odds with, which is often for the best. In Bruno’s world immediate pleasure triumphs over real joy, passion is preferred over sentimentality, and superficiality stands above depth. While his actions might leave a lot to be desired, there is something about his hunting his desires at every fork in the road that we, like Roberto, find admirable, and emboldening. And, though the two men might seem antithetical, they aren’t at heart all that different. While Roberto might frown upon Bruno’s trying to ‘make it’ with every girl he passes, he still secretly harbours his own desire to ‘make it’ with the girl who lives next door. The only difference is, that while Bruno would long have ‘made it’ and moved on, after more than a year of living there, Roberto hasn’t yet hardly spoken to her. Which, really, is the more preferable position to be in? Thus, “most of the film involves the gradual melting of Roberto’s defences as he comes to embrace what Bruno (for better and especially for worse) represents: “the easy life”—obligations later, live now.”

But, Bruno is no easy villain, and Roberto is no perfect hero. Morally, the shy student is our surrogate, but much like the scholar himself, we are drawn irresistibly to Bruno. His charm, his audacity of action and “seductive effrontery to basic moral codes” is, well, seductive. One can’t look at Bruno and not wish that they were a little more like him. How much easier might life be? Would we be more successful? Would we be happier? His isn’t a Leopold and Loeb superiority complex and, similarly, he doesn’t suggest that this refusal to be bound by burdens of responsibility is his privilege alone. In fact, throughout the film he encourages Roberto to indulge himself in such behaviour, to engage more actively with life and take what is there to be taken. And, to the extent that we are Roberto, he encourages us to do the same. In a world full of those who don’t, there stands so much to gain by being one of those who do.

‘Il Sorpasso’ has all the caveats and cautions that you might expect from such a story. Bruno isn’t a carefree adolescent, so fruitfully in search of life’s pleasures, and so free of that which weighs upon the rest of us. He is, as we learn, approaching middle age, with a failed marriage hanging round his neck, and a daughter who has about as much respect for him as he does for everyone else on the road. He walks into every bar without the money to pay, and lives a life totally devoid of any real relationships. If he had a little more self-awareness, his failures and short-comings would probably eat him alive. Roberto, for all his decorous reservation, suffers from a timidity that borders on infuriating. And, though by the film’s end he might have freed himself ever so slightly from the shackles of his inhibition, we get the sense that without Bruno egging him on, he will always be too shy to truly engage with the life that’s in front of him. In the middle of the movie, the two men pull over and head into a roadside bar. Bruno goes straight over to a table of people, only one of whom he hardly even knows, and begins to ingratiate himself with them all. Shortly, he gets up to dance with one of the girls in the party, which leaves a free seat at the table. Roberto looks over at the seat, and at the people around the table, drinking, and smoking, and having a good time, and knows that the solution to his isolation is so simple. Yet, he can’t bring himself to do it. It is a brilliant moment that encapsulates the two men, and the difference that divides them. By the time Roberto has already considered, debated, thought and rethought his actions, and decided against risking failure, Bruno has already sat, and stood up again. His is a life moving at twice the speed. It is, also, an extremely grounding moment for us, the audience. In the context of the film, we feel certain that Roberto will take the seat, take the leap, and assume the risk, for he has started to see the rewards reaped by those who take agency; we certainly wish that he will. But, how many times have we been faced by the same empty seat? And how many times have we not sat in it? It seems such a small decision, that requires little courage and presents little risk. But, in real time, the stakes could hardly seem higher. Our lives are made of such small moments, and it is these moments that make us who we are. If you reach into the world to take from it what you want, you’re liable to get your hand bitten, at least once or twice. But, does that mean it’s better not to reach or to take from it at all?

Risi is quick to highlight, more often than not with comedic effect, the costs of living ‘The Easy Life’ (the title under which the film was released in America), and they come as no surprise. But, the themes at play here have implications that stretch beyond the small world inhabited by our incongruous leads. With its theatrical release in 1962, the director speaks directly to the post-war generation, to the victors who enjoyed the spoils of ‘Il Boom’, to the consumerism and paper-thinning culture that was to follow. Bruno, a man who makes fun of everything, whether it’s love, family, rules, institutions, or Michelangelo Antonioni, represents a change in tides towards modernity. And, while Roberto (who is more representative of tradition) seems to be the one who changes and grows throughout the film, the story is really a moral fable, and the lessons that have to be learnt are in fact Bruno’s. Roberto, as it turns out, is just the cost of his lesson. For a film that spends the first 104 of its 105 minutes reasoning that the diffident Roberto would do well to take a leaf out of Bruno’s book, that final minute turns it all on its head.

As the two take the Via Aurelia back home, to Rome, at the end of their weekend, the shoe finally finds the other foot. As Bruno settles into his typically ferocious speed, they find themselves stuck behind another ‘surpasser’ – a car that won’t let them pass. Roberto, feeling the wind through his hair and the blood in his veins for the very first time, encourages Bruno to go faster, faster. After losing ground on a series of hairpins along the Tyrrhenian coast, Bruno finally catches up with the car in front, and just as it looks as if he’ll take him on the next turn, a bus rounds the corner, forcing Bruno to swerve the car away from the road and out of his control. He hits a pillar, which throws him out of the car, but sends it off the side of the cliff, with Roberto still in it. As a crowd gathers behind Bruno, who looks down and out into the abyss, a policeman asks him whether he was a relative, to which Bruno replies forlornly that “His name was Roberto. I don’t know his last name, I just met him yesterday”.

The film’s ending comes as a great surprise. At least, it does in the sense that death should come to Roberto – the one who’s changed and seems to have grown since the beginning of the film. But, having Bruno be the one to be killed would be overtly puritanical, and so much so that it would water down the film’s fable. To see them both careen down the cliff seems a tempting proposition, but in the cinema there must always be one man standing, otherwise there’s no one left to learn the lesson. But, to have Bruno, the hell-raiser, the carefree ‘kid’, the man of today and not tomorrow, be the one who survives is all the more poignant, and the cost of this ‘easy life’ becomes all the more clear. Still, it is damning, since if we are Roberto, then it is he as much as us who is punished for trying to bend with our wills. Especially considering that, frankly, he would do well to carry just a little bit of Bruno inside of him, as all of us would.

There’s no way, that of all the movies I watched in May, ‘Il Sorpasso’ was the best. Nor was it my favourite. The first title goes to ‘Lawrence of Arabia’, which wasn’t as much a movie as it was a religious experience; an unfathomably masterful testament to the power of the cinema, of sight and sound. The latter of the crowns belongs to ‘Le Samouraï’, which is the greatest work of one of the medium’s greatest directors, and an unsurpassable expression of style in the cinema. But, what I find so compelling about ‘Il Sorpasso’, is the exploration of these two types of people. These two types of people that are all around us, that in one way or another include all of us, the depth in exploration of which I have never seen before The conflict of their dynamic isn’t a means to an end, and there’s no judgement as to which of the two men is more deserved of our love, or our respect. It merely puts them together, behind the wheel of a car, and lets us come to our own conclusions. I find myself frequently in Roberto’s shoes, as the more timid of two (or more) people, who wishes they had it in them to take a seat at the table, but worries that they’ll fall short of other people’s expectations once they make their presence known. But, one wonders how many opportunities one might miss out on by not throwing their jacket on the back of the chair, and throwing themselves into the mix. In a world where there’s only two types of people, I wonder where best on the scale it is to be, and how one sits oneself at the best seat in the house. Of one thing I’m certain, if there’s only those who do and those who don’t, I know which I’d rather be.

You may also like

A GANGSTER’S PARADISE: JUNE

“A cartoonist’s only commandment should be: Thou shalt not bore.” – Tex Aver

What A Little Love Can Do

Tellus integer feugiat scelerisque varius. Sit amet volutpat consequat mauris nunc congue nisi. At u

A MAN & HIS MACHINE: JANUARY

“When you’re racing, it’s life. Anything that happens before or after is just wa

Post a comment