A REMEMBRANCE OF THINGS PAST, PART II: APRIL

“I live with this movie every day of my life.”

– Martin Scorsese

Imagine my curiosity when Martin Scorsese said of a miscellaneous Italian flick: “I live with this movie every day of my life”. What does that even mean? I had, at the time of reading, watched only one of director Luchino Visconti’s films. That was 1960’s ‘Rocco and His Brothers’, a movie I thought rather good, but ultimately one I haven’t felt compelled to watch again since. From the pictures in the article, I could see that it was a period piece, and though I’m generally fond of period pieces, my interest in them sits in close alignment with the cut of the particular periods trousers. I find it hard to be enthusiastic about a costume drama prior to the 1920’s because the trousers too closely resemble the reprehensible slim fit of today’s standard. The twenties are truly where my excitement begins, though, that excitement is typically dampened by the ubiquity of the waistcoat (the appeal of which I’ve never understood). As trousers are let out a little wider in the 1930’s, my appreciation really starts to ramp up with them. It is, then, for the movies set in the forties, when trousers were at their absolute widest, that my love knows no bounds. Give me a movie, a motion picture, a film or a filum; make it about war, peace, love or loss – if it’s set in the 1940’s, I’ll be the first one in line, and the last one to leave. (Don’t get me started on movies actually made in the forties.) The fifties I find often as interesting, though as the decade drags on, trousers start to see flat fronts, and by the sixties slim fits are back, and pleats are a thing of the past – a sad loss from which we’ve never quite recovered. Not in good conscience could I consider anything set after the 1960’s a period piece, and so the conversation ends right about there.

Needless to say, I wasn’t enthralled by the prospect of a three hour, Italian dubbed, nineteenth century historical drama; an epic, set outside the confines of a city (by far the superior setting). I decided, however, based solely on Scorsese’s comment, to give ‘The Leopard’ a chance.

Walking away, I was a little underwhelmed. Sometimes, not infrequently, I come out of a movie and recognise that I’d probably seen something ‘great’, but didn’t really feel myself connecting with it. That is minorly overstating how I felt returning home from Visconti’s ‘The Leopard’. I knew I’d definitely seen something, and certainly what I’d seen had been photographed beautifully, but I felt myself wanting to like it more than I actually did. Had we been destined to meet that night walking on the Waterloo Bridge, I’d likely’ve summed it up to you as an ‘interesting, rather meandering movie about the upper stratum of society, and how it fell from grace. A little moving, more than a little long, and bound by its context’. That was in January of last year.

As winter waged on, as always it will, I reached a little further into Visconti’s filmography – starting from square one and skipping none but ‘The Leopard’ (which I hadn’t much desire to see again quite so soon). Spring finally sprung, and much like the daffodils in Francis Russell’s nearby square, I could feel the movie beginning to bloom, and taking shape in my mind. There was something about it, especially about that penultimate scene; something I hadn’t been able to see, something I grew sure had eluded me. A short while after that, somewhere around summer’s middle, I found myself with Lampedusa’s book (from which the film is adapted), read and re-reading it, searching for some semblance of answers. By the time the leaves turned and winter was back around I was calling everything into question, feeling certain about two things, and two things only. Firstly, that while I’d watched the film all those many months ago, I hadn’t truly seen it; secondly, that the movie I’d been seeing in my mind throughout the four seasons since was unlike anything I had ever seen. It is, now, a little over a year later, and I’m starting to see what Marty meant when he said that he lives with it, every single day. So I guess it’s a good thing for us both that we didn’t meet that night on the bridge.

For all my likes and dislikes, idiosyncrasies and normalcies, my sympathies and otherwise, when I really get right down to it, I tend to think that most movies fall fairly neatly into one of three categories. On the surface, these three categories might imply three different levels of merit, beneath the surface however, they insist it.

In the first, we find a shameful majority – those movies which one ‘consumes’ without rousing even the slightest sense of cognitive ability (I won’t mention any names). In the second, a nobler minority – movies that engage us, either emotionally or intellectually, preferably both; turning the cogs in real time. As an unabashed advocate for escapist entertainment that remains grounded in reality, I find many of my favourites at home here (‘Casablanca’, for one). Lastly, and most leastly, is the golden goose category. Though a scarce few, these are the movies that grind the cogs to a halt, gumming up the works entirely and pausing life in all its trivial consideration. Such pictures as these (‘A Place in the Sun’) entrench themselves in the forefront of my mind, and make my mundane reality feel like the interruption. But, provoking as they might be, hard as they may try, the ceaselessness of time on this cockeyed caravan always wins out in the end, and life prevails.

Admittedly, some movies are hard to place; hell, some even manage to resist the immediate condemnation they deserve (‘Ace in the Hole’). As a closeted optimist, I’m often blind trusting of the ones that I enjoy, but which largely wash over me. Some movies require contextual knowledge to really be appreciated – the lack of which is a shortcoming that can be corrected with time. Some require greater age, or life experience, to really be ready for them – the former of which certainly comes with time, the latter often not, much to my regret. Aside from all the hell and condemnation, all of the above could be said of my initial reception of this ‘miscellaneous’ Italian movie. This brings me to the hidden, truest and most time tested, forth and final category.

These are the movies that slip under the radar, simmering somewhere beneath our surface, bringing themselves to boil, gently, and only gradually over time. These are the ones that can change us, fundamentally, as people. At this, the time of writing, there are only three movies I’d deem worthy of this unicornal category. With ‘Vertigo’, which I initially disliked, I was drawn irrationally to repeated viewings over a number of years. It was, as I like to say, during the opening credits of my fifth ride around that I came to realise its dizzying power. In the case of ‘The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp’, on the other hand, I quickly recognised its potency. Its durability, however, I only appreciated with hindsight, about a year down the line, and after a crucial second watch. What binds ‘The Leopard’ together with the two aforementioned titles is, what seems to me a prerequisite for any fourth category contender: that it left something behind; footsteps that I could only grow into with time. I walk away from watching these movies, only really seeing what they reveal in a surface level light. But, as time goes on, as their plots and what seems to be their stories fade away, something else steps into the limelight, something which I’ve come to recognise from my own life. What makes ‘The Leopard’ stand apart from the other two lap leaders in the marathon of cinema, is that it didn’t require a repeated viewing. It, somehow, raised itself from obscurity, from within the mess of motion pictures, the memories of which exist somewhere between my heart and my head, right to the very top of the pile.

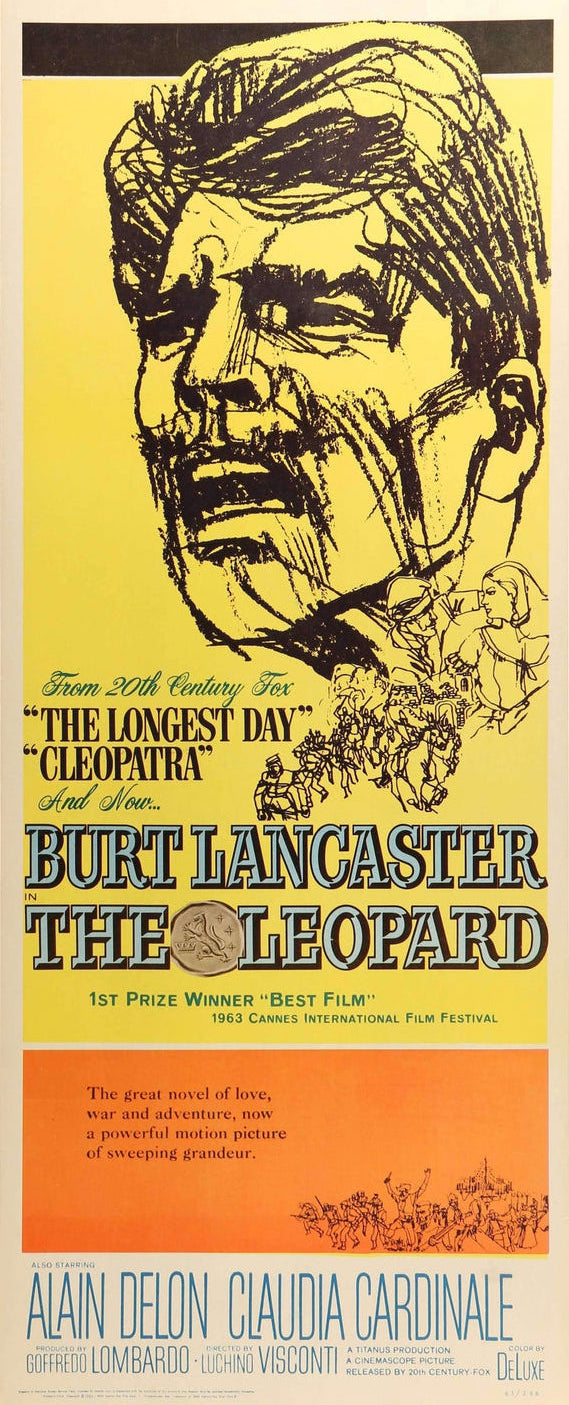

‘The Leopard’ opened at a curious time and place in cinema’s history. The film premiered in March of ’63, at the Cinema Barberini in Rome. It was a time when audiences were withdrawing from the widescreen epics, the sort of big-budget fiascos that’d become the ‘mode du jour’ in Hollywood and abroad by the previous decades end. After the cultural corner turned by the French’s new wave and the release of such movies as ‘La Dolce Vita’, the blockbusters and super-productions of the major studios felt like remnants of a parade gone by. Shortly, the studios of old would die out, the mega media conglomerates would rise from their ashes and the money men would turn away from tradition, chasing the zeitgeist right down into the drain. And, though its place and release date might imply modernity, as David Weir wrote for the BFI Film Classics series, ‘The Leopard’ is, in many ways, “the apotheosis of traditional filmmaking, involving high production values, big-name stars, a bestselling novel as the basis, and […] a celebrity director”. That is to say, it was already out of fashion, before it was even out.

Similarly, the period spanning the fifties and early sixties, known as ‘Hollywood on the Tiber’, wherein Rome (and Italy as a whole), emerged as a major location for American filmmaking, during which time lavish studio productions with casts of varying nationalities were common place, was also coming to an end by 1963. (The films from this period are not without their charm, though few have defied time – ‘Roman Holiday’ being the most notable exception.) And, while ‘The Leopard’ is certainly more an Italian production than not, and thus not on the guest list of Hollywood’s own Roman holiday, the casting of Burt Lancaster (a bonafide American star) in its titular role, significant financial backing by MGM, and international distribution by Twentieth Century Fox still place the films release a little awkwardly. Its original theatrical release, butchered by the studio, dubbed into an English spoken production, and publicly repudiated by Visconti, did all but help its case.

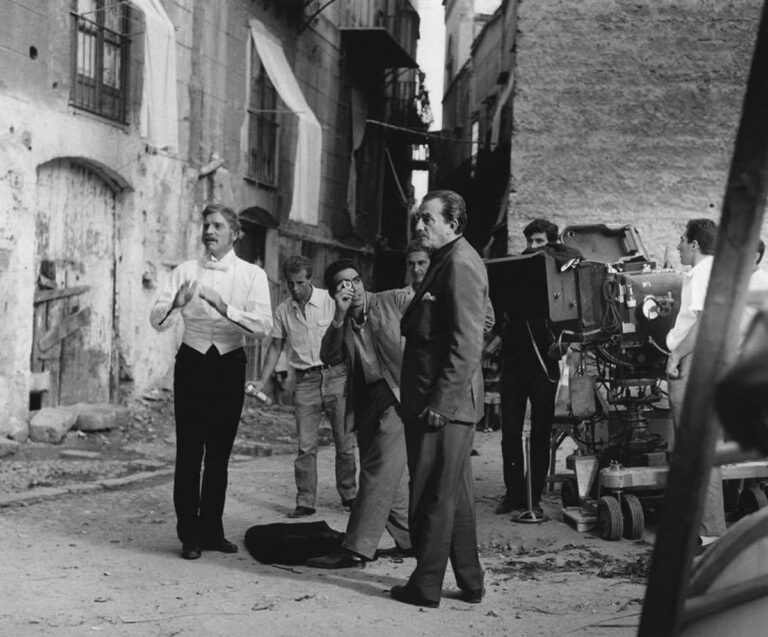

For the films director, whose roots lie in the Italian movement of neorealism, but whose flower blossomed into a uniquely operatic and baroque style of his own (though just as Italian), ‘The Leopard’ marked an equally undetermined phase. Those familiar with neorealism and the films birthed by the ruins of the Second World War, and with Visconti’s later work (‘Death in Venice’, ‘Conversation Piece’), will note the chasmic dichotomy between the two styles. After a brief mid career phase marked by movies that were neither here, nor there, thematically nor stylistically, the director fought his final tussle with neorealism in 1960, with ‘Rocco and His Brothers’. Though, with its 177 minute runtime, significantly sprawling scope and a style that leans towards the operatic, it foreshadows an imminent departure. Three years later, with the release of ‘The Leopard’, Visconti had arrived. And, though it won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, and certainly received some acclaim upon release, many saw his loving and lavish picture of power and privilege as a betrayal of the values he had once helped to propagate. Thus, even the attachment of his name atop the film’s poster sparked controversy. But, Visconti’s partiality for contradiction was never a secret, and it is crucial to the film’s brilliance. Jean-Andre Fieschi, writing for ‘Cahiers’ at the films release, went as far as to call him “the Prince of contradictions”. Though, in the context of his review, did so rather unaffectionately. In the context of his oeuvre, ‘The Leopard’ tucks into place; the change between before and after seems gradual, and the discrepancies subdued. With that being said, putting a film like ‘Ossessione’ (his first directorial attempt) in the same sentence as ‘L’innocente’ (his last), still feels about as normal as a nudist colony in the west wing of an old people’s home.

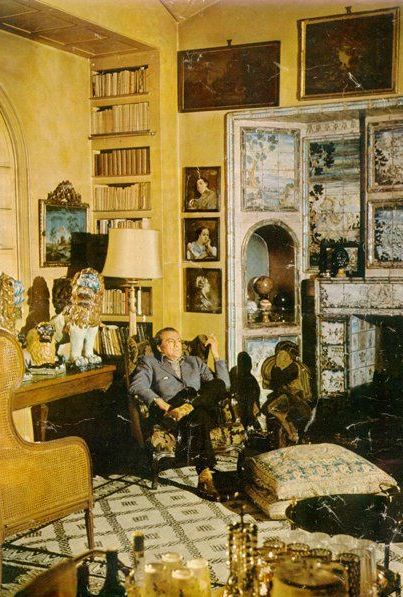

Being born into a long line of Milanese nobility in 1906 afforded Luchino Visconti, Count don Luchino Visconti di Modrone, rather charmed beginnings. (It’s been said that as a child, the roof atop Milan’s Duomo was the closest he came to having his own private garden.) With a lifetimes exposure to art, music, theatre and opera – the latter of which he enjoyed from the Viscontis’ private box in La Scala – in the space of a single childhood, an international art education, and a level of taste typically reserved only for those raised in such privilege, Visconti seems the princely product of both nature, and nurture. His was a life lived lavishly, in stately homes and sophisticated company; bouncing from opera to film, to the stage and back again. He was elegant and exacting, as entitled as he was ruthless in his search for perfection. He was, also, a fervent Marxist who’d card carried for the Italian Communist Party, fairly unambiguously gay, and a devout Catholic. How all the pieces of that puzzle fit together, the Lord only knows. Such conflicting ‘inconsistencies’ are rife within his individual films and, as I mentioned previously, are immediately evident when taking a more general look at his filmography. Thus, while early films like ‘La Terra Trema’, for example (an emblematic piece of neorealism, funded in its entirety by the PCI), suggest a man at the forefront of cinema, facing forwards towards a future, the remainder of his filmography reveals an adamant retrograde. Today, Visconti is mostly remembered for the latter, for his gloriously indulgent portraits of beauty, decadence, and the aristocracy – i.e., that and those which, politically, he believed must be destroyed. It seems utterly inconceivable that the very same person could’ve captained such drastically different ships, but, that’s the Prince of Contradiction for you.

Coincidentally, the novel’s author was also born into a position of prominence, for Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa was not only the 11th Prince of Lampedusa, but also the 12th Duke of Palma. Much remains a mystery about the writer and his life, and its little surprise – he was described as taciturn, solitary and shy, and wrote of himself that, “Of my sixteen hours of daily wakefulness, at least ten are spent in solitude”. Where bodies of work are concerned, there is even less to go on, with ‘Il Gattopardo’ being Lampedusa’s only completed piece. Sadly, having been rejected twice, in 1956 and 1957, it was only in 1958, a year after his death, that his book was finally published. But, no matter the lack of detail in the author’s lived experience, he is revealed transparently in the books subject matter, particularly in his handling of it, and in all that can be inferred from it as auto-biographical. Its titular character, Prince Don Fabrizio, “is the Prince of Lampedusa, my great grandfather Guilio Fabrizio”, he wrote to a friend; the (fictional) Prince’s nephew, Tancredi, is understood as a composite of the author’s adopted son and another Sicilian nobleman. Similarly, the town of Donnafugata, along with the fictional family’s summer palace there, and the Villa Salina on the outskirts of Palermo are all based on real locations that, in the first and only completed chapter of his autobiography, the writer referred to as the “Places of My Infancy”.

With that being said, while much continues to be made of this curious parallel between the book’s author and the film’s director, I find this detail to be more coincidental than I do consequential. Certainly, Visconti’s first hand knowledge of the sorts of characters, the familial dynamics at play, and his familiarity with the milieu couldn’t hurt his handling of the material; certainly, I won’t refute Roger Ebert’s claim that the film was “directed by the only man who could’ve directed it”. What I do abnegate, is that the reason for this is Visconti’s birth into, and experience in high society, and thus the supposition that, just because of the golden trimmings in their family trees, it was his story to tell as much as it was Lampedusa’s.

As in all great adaptations, of which there’re unremarkably few, Visconti takes liberties: adding a rather extensive battle sequence and omitting the books final chapter – which takes a large leap forward to the end of the Prince’s life. The revelations of that chapter are stricken entirely from the film, and are neither alluded to, nor foreshadowed. In this way Visconti alters the text, carving out from it that which he wanted to tell. But, the transference from prose to picture stills feels earnest, and true. Though the focus of the film’s story shifts ever so slightly, what remains is what’s crucial to a good adaptation – feeling. More important than the mere fact of the class they were born into, is the position both Lampedusa and Visconti found themselves in, later in life, as adults, as products of their time and place, and their respective personalities. As the last Prince of Sicily, Lampedusa was, by the nature of time, a man doomed to forever wander between the winds of modernity and antiquity. “Don Fabrizio expresses my ideas completely”, wrote the author to a friend, and, while it’s healthy to account for a degree of projection when such heroic protagonists are involved, it isn’t hard to hear the author’s own voice behind the Prince’s sorrow that, “I belong to an unlucky generation, astride between two worlds, and ill-at-ease in both”.* Visconti, more so by his own nature, was at the mercy of a similar uncertainty – certainly, there seems little question that his head and his heart were on either side of the very same, and very much opposing ends. Both the book and the film yearn for a past, and we feel each artist reaching wistfully into their own history, and ultimately, finding themselves falling just a little short. There is, however, a counteracting force in their acceptance of fate, and almost an appreciation for the necessity of change, and growth. Though the story swells with regret over the crumbling of an empire, as film critic Scott Tobias writes, “its feelings are complicated by the wise Prince, who recognizes his place on the wrong side of history”. If we view the Prince of the novel as a surrogate for its author, and the Prince of the film as the stand-in for its director, we find in either medium a man devoid of ignorance; a man honest in his vulnerability; a man who finds himself stuck between the devil and the deep blue sea. But, such sentiments don’t reveal themselves so readily, and themes as personal as these hide behind the shadows cast by the Prince’s fairly formidable figure. Where we begin to find them, is at the writer and director’s true corner of convergence: style. Where Lampedusa’s prose are ornate, sensual and evocative, Visconti’s camera is languorous and romantic. Where the writer’s sense of sadness read between the lines, the director’s search for lost time paint the ‘spaces’ in his mise en scène. And, it is here, in Visconti’s imagery, that we find the key to opening the pictures rather imposing gates.

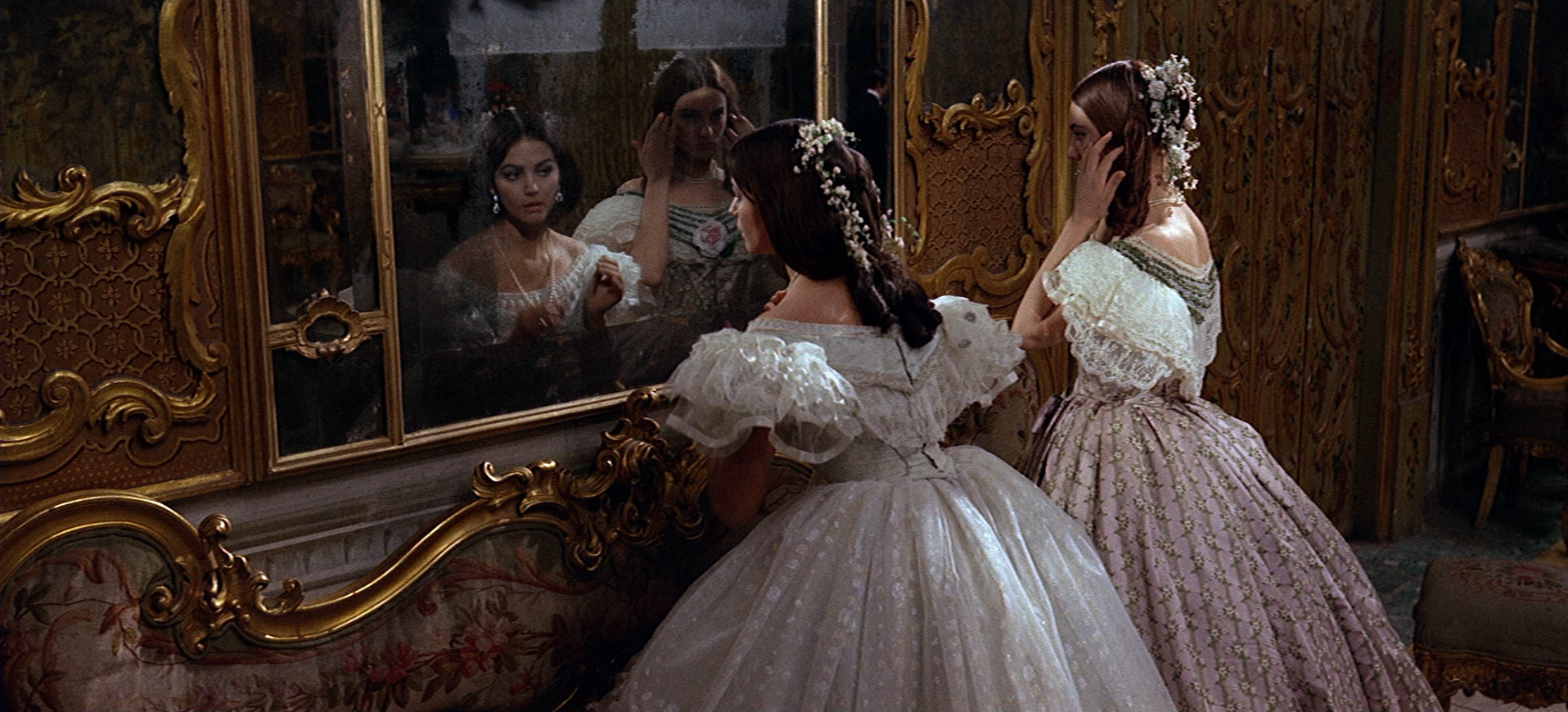

‘The Leopard’ is every bit as beautiful as a film possibly could be. And then a little more so. Visconti, along Giuseppe Rotunno (the films cameraman, to whom the director is greatly indebted), portray this sweeping environment that, while harsh in its heat and unforgiving in its terrain, is eternally captivating. Where the ‘beauty’ in a period piece like ‘Barry Lyndon’ is cold and alienating, here it is warm and inviting. The film’s Sicily is all sun, sea and olive trees, and Visconti takes the time to let us bathe in it with the same languid laziness as his principal characters.

Whether gazing at the stars in a midsummer night’s dream at Donnafugata, or falling asleep beneath the frescoes, laid out over a rich velvet sofa in the palazzo’s drawing room, ‘The Leopard’ is, if nothing else, an exercise in resplendency. Even the battle sequence plays like a quick flip through a catalogue of Renaissance paintings. The films interiors, courtesy of production designer Mario Garbuglia, are unceasingly sumptuous without ever feeling gauche, or distasteful. From each vase and every curtain, to each cloth on every dresser, no stone is left unturned; every inch of their world is considered, and the objects that fill it so effortlessly reflect the characters in a thoroughly majestic manner. But, while the images alone can speak for themselves, the point here is far more deliberate than beauty because they can, or, beautiful because it is.

About midway through the movie, Father Pirrone (the family chaplain, and the Prince’s friend) admits to his curious clerical counterparts that the Prince and his people “aren’t easy to understand. They live in a world apart, not created by God but by themselves, during centuries of very special experiences, of troubles and [of] joys”. This is said as much for them, his audience, as it is for us, their audience. What it means to us is that the Salinas aren’t easy to empathise with – which is, naturally, the very obstacle the film must hurdle if its tale is to have any resonance with us at all. It is impossible not to bring in our preconceived notions about the aristocracy, and any disinclination we might feel for lamenting their demise is not unfounded, and it seems only to grow with time. So, Visconti appeals at first not to our heads but our hearts, and it is through his imagery that he welcomes us so warmly. His visuals become the key foundational tool in exercising our emotions – translating this otherwise distant and unfamiliar world with all the splendour and grace of the Prince himself. And, for our part, it is a welcome that we receive most gratefully, for there’re few places we’d rather spend the time than with the Salinas, in their Sicily. To be sure, Visconti isn’t just rolling the camera and recording the beauty in front of him, he is crafting images to delight us, deliberately.

What’s also at play here is our sense that Visconti is wearing his heart right out on the very forefront of his sleeve. If the director is going to show us the story of their loss (a loss which, politically, he believed in), then he also assumes the responsibility of showing us all that he himself regrets will be lost – juxtaposing the story and its style – and there is tragedy in the discrepancy between the tale of loss that he tells, and the love with which he tells it. (I refer to this dichotomy between sentiment and content as the ‘Liberty Valance Syndrome’.) His love is a hidden presence in each scene, and while a sense of pride is felt in every frame, it stands in direct contrast to the film’s morality. But his sincerity is palpable, and the way they say that listening to somebody talk about something they love is exciting, here we watch someone show something they love, and it is just inspiring. Even in modes as technical as camera movement, one feels a gentle melancholy, and a tenderness behind it. The camera itself feels as enchanted by each scene as the rest of us, and it seems almost hesitant to start or to stop; though, when it moves it glides, and it’s a perfect compliment to the beauty that it captures. Suffice it to say, within the world of ‘The Leopard’, I daresay the very notion of beauty found its fullest expression, and it is used brilliantly to draw us gently in to the story. But, the beauty here is on double duty, and it serves further purpose than just to welcome us into the Prince’s most wonderful world.

The design of Visconti’s mise en scène (generally defined as everything within the frame: sets, props, actors, lighting) certainly shoulders this duty. Nothing is arbitrary: the composition of every frame, and the positioning of every face and object is placed to indulge our fascination. And, while much has been made of Rotunno’s use of deep focus throughout the film, what’s interesting is that unlike a Welles or Renoir, Visconti uses it not necessarily to further the development of the plot, but to express the story’s themes. A large depth of field (whereby everything is in focus) is typically used so that we can see various information on varying focal planes, simultaneously, without changing focus from one thing to the other. For instance, being able to see Character A’s face as he says something objectionable, and being able to see Character B’s horrified reaction to it, at the same time, even though she stands much further away. In ‘The Leopard’, deep focus is used just so that we can see. Whether it’s a bouquet of roses in a vase on the dresser, a curtain blowing gently in the wind, or a gold gilded door handle in the deepest darkest background, Visconti wants us to see it all. Through the combination of his staging, and Rotunno’s technical wizardry, we do see it all, and all at once.

At a first glance, this rather unique utilisation of what can be a very powerful storytelling tool might seem a little tawdry. The way we might scorn the Prince, his family, and the rest of his class for their seemingly unadulterated excesses, we might view their homes and all its decoration as a mere extravagance, or privileged indulgence; by the same token, we might view Visconti’s use of deep focus just to show it off as equally trivial. However, if we bare in mind Oscar Wilde’s rather antiquated, and elitist notion on the subject of art for art’s sake (one that, I must confess, I have some sympathy with), that “nothing is really beautiful unless it is useless; everything useful is ugly, for it expresses a need, and the needs of man are ignoble and disgusting”, then we start to see truth through Visconti’s camera, for a greater expression of the Leopard and his lions could scarcely be found. Thus, it is as profound an expression of the the characters’ morality, as it is subtle. Visconti, a man who would’ve undoubtedly had his sympathies for Wilde’s words, uses his mise en scène not just for the purpose of story, but to communicate this uniquely aristocratic ideology, one that applies both literally, and metaphorically. What’s more, in his depicting this world with such charm and warmth, one that we can’t help but be drawn to, Visconti makes us complicit in the Salina family’s privilege too. And, for these three hours, we are gladly grateful for it. Through the photography, the decor, the design, and the placement of people and position of objects, we empathise with them, we buy into their struggle and, ultimately, we feel remorse at their loss. Thematically, it comes full circle, emotionally, it brings us ever closer to the characters. It deepens our sense of time, of place, putting a whole history into perspective such that we can feel as intimate with it, and attached to it, as the Prince himself.

The culmination of this comes near the films end, during the ballroom scene at the Ponteleone Palace – the grand finale of the film’s visual design. Having spent half the night listening to Verde and watching the waltzes to match, we find ourselves in the palazzo’s dining room, where mountains of cake and other such sweets pile up beneath ornate, gold candelabras. Until now, the Prince has largely regretted that he came at all, and his anhedonia is only exacerbated by his sense that extravagances such as these have affixed a fast approaching expiry date onto them all. But, his waltz with Angelica, which he has just danced, has afforded him a brief spiritual revival, and he feels greatly better for it. Knowing that two lovers would really rather be alone, he declines the invitation to dine with her and Tancredi, and enters the dining room along with everybody else. As the mass body builds, we lose the Prince among the herd, and Visconti takes us over to Don Calogero, who we find gorging himself on an entire plate of chocolate cake, and probably the plate itself too. Don Calogero (Angelica’s father, and the town mayor of Donnafugata), is the representative jackal or sheep, the king of the soon-to-be bourgeoisies, the face of the force that will soon steal everything away from the Leopard and his lions. But, that stays on the horizon, and though time wears on, the night is still young. Seizing his opportunity to do what everyone else already is, Calogero tries his hand at conversation, picking as his victim the unfortunate gentleman standing next to him. Short of anything witty or discerning, he brings up the golden candelabras, and comments with contrivance on their elegance. The Prince passes behind them as the gentleman tells the mayor that the candelabras are from Madrid; a gift to the host’s grandfather from when he was the ambassador there. Rather than referring back to the mayor, we cut instead to the Prince, who pays little attention to the two men, but is well within earshot. As his eyes wander round the room, wondering among whom he might be left alone, we overhear Calogero’s repugnant response: “How much land would they be worth!”. It is a subtle, yet fatal blow, and its significance isn’t lost on the Prince, who pauses, his face rounding with regret; the sadness settling back into his eyes. Soon, such things will be appreciated, at best, for their use – what’s worse, is that the inherent ‘value’ in beauty, in history, or in simple sentimentality, will soon be conflated with value of the monetary kind. Beauty will no longer be in the eye of the beholder, but in the eyes and acceptance of the masses, whose only way to evaluate it is by how much it cost. By this point in the picture, we have become dutifully attached to the Prince, his world and his way of life, in all that represents it and all that it represents. Even though Calogero’s comment is probably a thought that would’ve crossed our minds were we to drop in at the ball, having been absorbed so gracefully, having become accustomed to and appreciative of our time in settings such as these, hearing it be said with such flagrancy, as though it were the right thing to say, as though it were the thought on everyone’s mind, makes our heart sink. What is more revealing, perhaps, is the insight that his comment offers into the looming changes as it pertains to society, and the men who will lead it. If the Leopards and lions are soon to be replaced by the jackals and sheep, then it is the Don Calogeros of the world who shortly will rule: mercenaries, self-serving men who know nothing of history, nor of the responsibility required for leadership; men without ideals, grace, or tactility. The Prince, and the people of his kind, for all their culture, their refinement, and their sense of duty, are out of time. They might be cut from a different cloth, but theirs is a cut above the rest. Still, there is no place left for them in the world of tomorrow. It is the first time we understand what this shift will mean, what it is we stand to lose, and how bleak the future looks because of it. That Visconti serves us this sentence through our connection with the decoration, through some golden candelabras, is more than just a little remarkable.

With all that being said, in ‘The Leopard’, the whole story of sociopolitical change is, really, a mere means to an end. A moving mediation on their loss though it may be, it isn’t that which lends the film such potency. As we walk into the Ponteleone’s Palace, we’re all set for the finish, the last hurrah and the film’s final embers before the Prince’s world goes up in smoke. But, as the party rages on, the people begin to blend in with the background, fading further into the frescoes, and the film sets itself ablaze, anew; revealing itself in an altogether different light. But, for now that will have to wait, for it’s high time the Prince himself took centre stage.

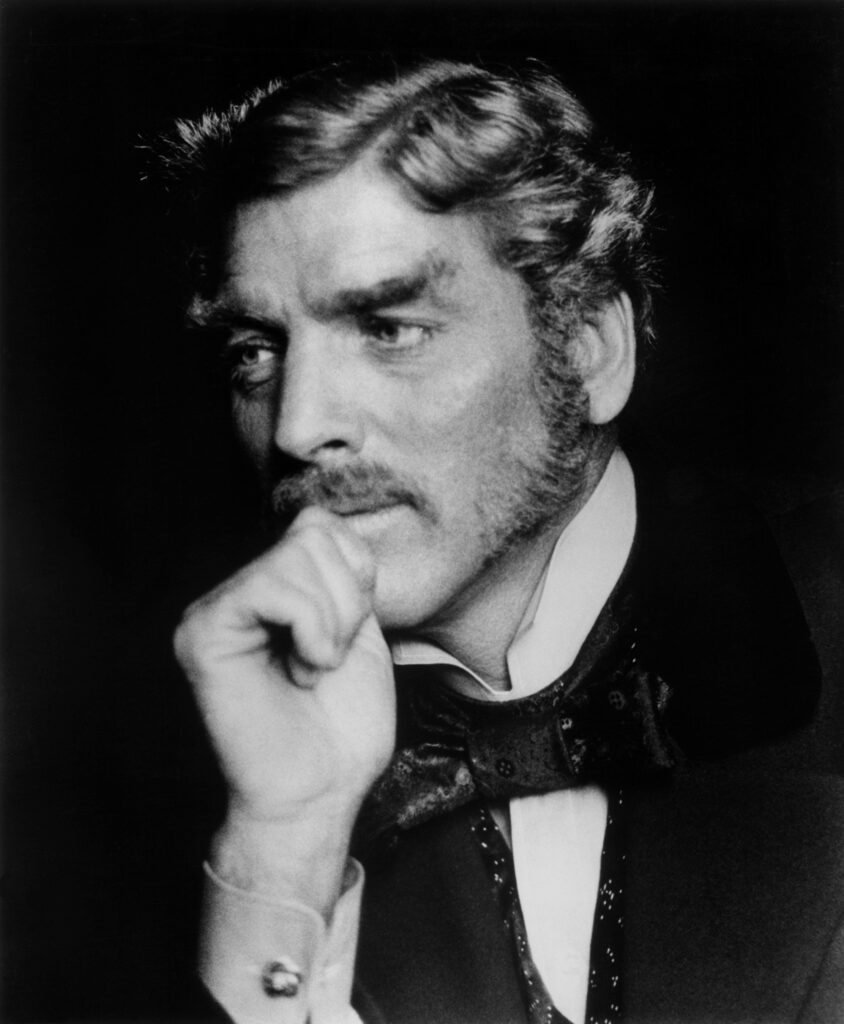

As much as I might eulogise Visconti for his deftness in direction, blocking, or superb vase selection, much of the movie’s weight falls onto the shoulders of its titular character, the Prince; the patriarch; Don Fabrizio Salina, the Leopard. He is the compass by which we navigate our way through the story, and it is through his eyes that we interpret its unfolding. I know of few films, if any, where the central character is so central to the movie. The role is an epic one, of career defining proportions, and if Visconti’d had his way it wouldn’t have been given to Burt Lancaster. MGM’s only condition, in exchange for the money to get the thing made, was that Visconti cast a studio star as its lead. Both Laurence Olivier and Spencer Tracy were approached by the director, and a whole host of other names were thrown around good measure, and even greater publicity. The producers then hired Lancaster, without consulting Visconti (who was outraged), and tensions between the two men began before the filming had. On set, the conditions worsened, with Luchino treating Burt disdainfully and making his feelings known to all. After a few long weeks of shooting, Lancaster’ had had enough and confronted Visconti publicly, letting him have it in front of all the cast and crew. The director was so taken by the passion and sincerity displayed by his star during his tirade that all was quickly forgiven, and in the place of scorn grew a mutual respect (and a friendship that lasted the duration of their lifetimes).

To say that Burt Lancaster gives the performance of his life feels ill-suited – he doesn’t go hell for leather in his portrayal of the princely aristocrat, nor does he lean into affectation or cliche. In actuality, Lancaster’s performance is perhaps the definitive statement on subtle screen acting. The version of the film most widely circulated today sees Lancaster’s Leopard dubbed by actor and serial dubber, Corrado Gaipa, and any audience member familiar with the Harlem native will immediately recognise that it isn’t his voice. (Even those unfamiliar will cotton on pretty quickly.) It is, therefore, solely on the actor’s physicality that the heavy lifting falls, and to use the famously British understatement, I’d say he manages to bear the load. At six foot two, and somewhere between 180 to two hundred pounds, Burt cuts a rather imposing figure, but his experience as a professional acrobat (until injury forced him to retire at 26), lends him an unusually supreme control over his rather monolithic frame. Thus, his movement is always considered, and remarkably graceful. But there lurks a perpetual physical threat, and an explosive sense of power that we feel the Prince is often at odds to restrain. Physically, he never boils over, as he does in his boxer-turned-gangster of ‘The Killers’, and his temperament never teeters towards the cold ruthlessness of his U.S.A.F. General in the ‘Seven Days in May’ – though we feel a very real capacity for both. The result, this combination of a feline elegance and an animal power, gives the Prince’s character an immense dynamism.

There is one moment during a hunting trip with his friend and confidante, Don Ciccio, wherein having been charged with ruining his family’s name by tying it to the mayor’s, his temper triumphs over his judgment. As he towers over Don Ciccio, snarling, we get our only glimpse into the furnace that rages beneath the calm and collected exterior. But, though the threat looms in the shadows of Lancaster’s performance, the Prince isn’t irascible, and his composure keeps him in check. Burt’s strength, with his grace and his gravitas, create a character of great assurance and authority, but, ultimately, as soon we shall see, of an even greater melancholy.

Where the Prince of the novel, and the Prince of the film diverge, is in the arc of their disposition. In either medium, Don Fabrizio isn’t the immediate subject of our empathy. The film’s opening scene, which is taken verbatim from the book, introduces a patriarch who is as feared as he is revered. He runs the family, and he knows it, catering to his own desires – which in this case means a visit to his mistress in Palermo. Even though the news of Garibaldi’s landing in Marsala is rather pressing, and has only just reached them, the family is at the mercy of his whim.

But, great ground is covered between the films open and its close, and while Lampedusa’s Prince remains largely the same, Visconti’s Prince undergoes a gradual change, not only winning us over, but demanding the empathy of an entire auditorium. What’s telling, is that all the key events in the book are present in the film (bar the closing chapter), and so too is almost all the dialogue. But, while in the book the Prince remains only our compass and our eyes, in the film he assumes the burden of its soul. It is, therefore, in Lancaster’s interpretation of the role – in which he admits greater gentility, and a growing fragility – that gives his characterisation such humanity. In exuding a rare brand of honest, vulnerable, yet strongly masculine charm, he towers above all in his portrayal of ‘manliness’ in the movies. Though, while he is a traditionally aspirational leading character, he isn’t perfect. And, while he mightn’t be moved to iron out all his shortcomings, he recognises what they are, and regrets them for what they’re worth. Like us, he is human, and he suffers from the same fallibility that we all do.

Early in the actors career, Lancaster fell victim to the studio’s proclivity to typecast, and he played fairly repetitious roles of the tough guy with the tender heart. In a sense, his role in ‘The Leopard’ is a variation on this tradition – one less cliched, and greatly more nuanced, but a variation just the same. As it was with those movies, though it’s realised most effectively here, the secret to Burt’s softer side is in his eyes. Visconti, for his part, saves the majority of his close-ups for the film’s final sequence, and it is the first time we see him extricated from his environment, and without distraction. Luckily, I needn’t indulge the urge to go on and on, for the proof is in the pudding (or, as in the Prince’s case, it’s in the desert wine digestif). In the film’s final breath, as he walks home from the party, we get one last glimpse at him in close-up as he kneels, looking up at the stars and wondering when will he be allowed among them. The shot is remarkably simple, but it is desperately affecting. Alone in the world and at odds with it, his face softens, like a lost little boy looking for his way home, and his eyes become the window into our common soul. In a single shot, we witness the universally human struggle of us all. I, for one, find it the most moving moment in cinema.

Atop the posters of recent re-releases, the film’s tagline reads, “Luchino Visconti’s Enduring Romantic Adventure”. The word ‘adventure’ feels a little inaccurate, but is used, presumably, because of the movie’s three hour run time. Even the use of ‘enduring’ seems a little erroneous, given that it wasn’t until 1983 that ‘The Leopard’ was actually released in its intended form. And, though it has undergone a fairly significant reevaluation since, it’ll have to wait a little longer than forty years before it can be given that title. With regards to ‘romance’, I’d argue that the very notion of it is woven indelibly into the fabric of the film – which is not, I assume, what the marketing team meant when they labelled it as such. With that being said, that is actually an out and out romance, and in a way, Tancredi (Alain Delon) and Angelica’s (Claudia Cardinale) coupling is the point that drives the plot.

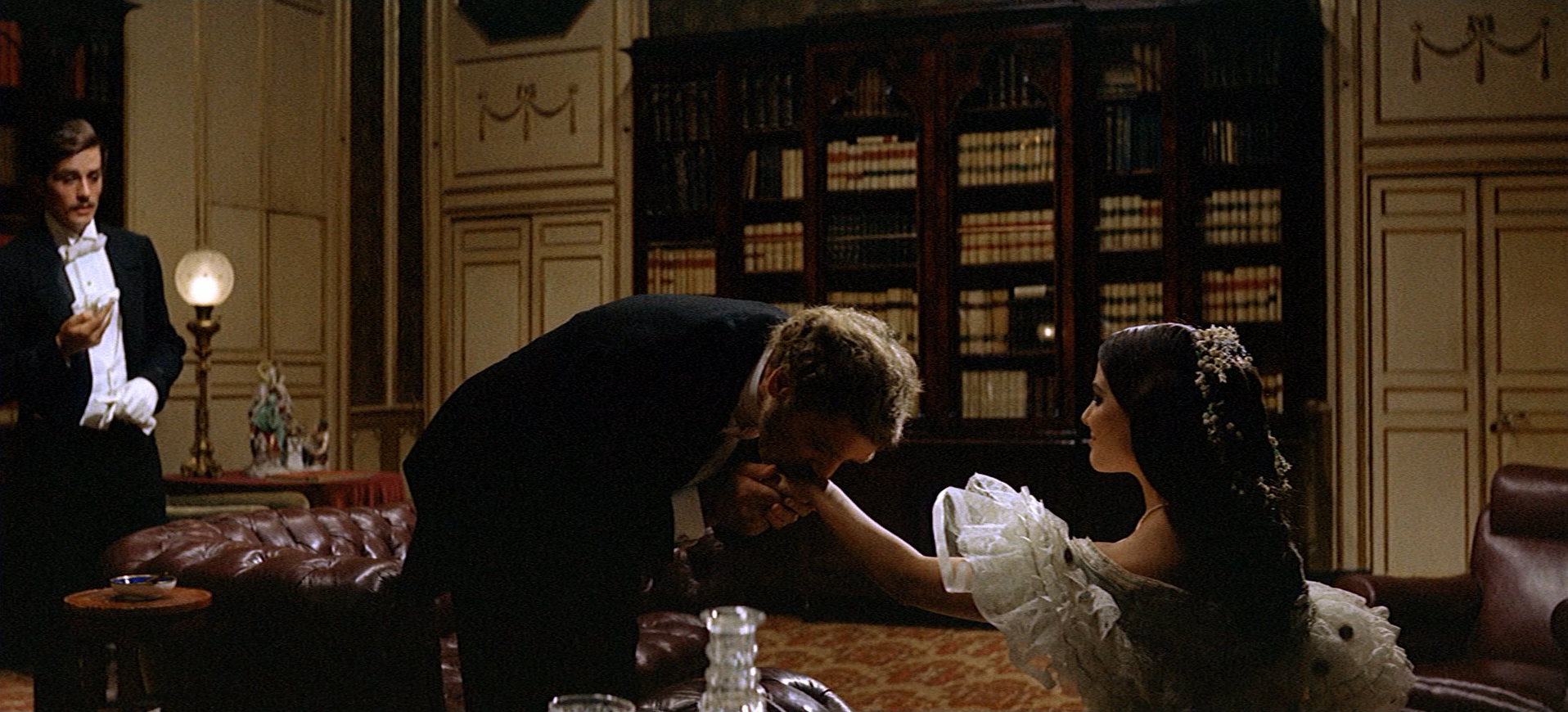

In the novel, though, their relationship has not only a beginning and a middle, but also an end (in the final chapter). Here, it is more of a ‘happening’ than it is its own moral tale; a necessary piece in the puzzle, so that we can get to the bigger picture. Cardinale, for her role as the pulchritudinous Angelica, might be the perfect casting (though I wouldn’t wish to split the difference with her turn in Fellini’s ‘8½’). She is both teasing and innocent, aware of the attention she attracts, but too childish to understand the power that she yields. She plays into her petulant beauty with charm and such ease that it’s little wonder why all the boys want a spot on her dance card. Though she mightn’t be of the same stock as the Salinas, there is an agility to her character, and she resists objectification. The Prince’s own attraction to her, therefore, feels more transcending than it does transgressing. Delon’s characterisation of Tancredi is interesting, because it is a rare role in which he plays against type. There’s little question that the Frenchman’s face is one of the most photogenic in movie history, but, where it is often used to draw us towards an otherwise cold, and unsympathetic character, here it is quite the contrary. At least, it is on the surface.

Tancredi is a buoyant, and perceptive young man, who seeks excitement and opportunity wherever he can find it. We know that the Prince sees some of himself in his nephew (who is more like a son), and, ultimately, it is to Tancredi that he entrusts the future of the family. Delon is likeable, and charming, with vigour aplenty, and with his close relation to the Prince it’s hard not to feel fondly towards him. But, where the Prince has integrity, Tancredi is impressionable, blowing with the wind in whichever way it prevails; the Prince might be the Leopard, but Tancredi is the one changing spots. And, as the film goes on, we recognise (as perhaps the Prince does too) that Tancredi is more akin to the jackals, and possibly even the sheep. One of the questions that consumed Visconti while on location was whether or not Tancredi, born half a century later would’ve been a fascist. If we take his malleable attitude, his lack of moral fibre and will to conform as evidence, I’d argue that we’re confronted with a rather unfavourable probability. And, while this isn’t a line of thought that I find particularly consuming, it does open up the film for different interpretations.

Politics are embedded inextricably into the film, and questions of Marxist rhetoric are to be found by those inclined to see them. Times are few and far between when the walls of the Prince’s world are broken, but Visconti picks his moment precisely. After a meeting with the Secretary of the Prefecture of Sicily, (who wishes to admit the Prince as the islands representative in the senate of the nascent Kingdom of Italy), the sequence that follows is that of the ballroom, which will (almost) comprise the remainder of the film. Visconti, however, as opposed to transitioning straight from one to the other, cuts instead to a wide shot of Sicily from atop a hill. As we see Donnafugata below, revelling in its golden hour, the camera slowly pans to the foot of the hill, and Visconti shows us a double dozen workers toiling away half way up it. Gradually, slowly, we dissolve into the ballroom, and the half-naked bodies of the proletariat are replaced by the elaborate dress of the waltzing ruling class. This personal interruption of an otherwise seamless dramatisation of the novel is not an unwelcome one, and such intrusions are the right of every artist. But, in the case of Visconti and ‘The Leopard’, it feels more like a reminder, than it does a message around which the film is fashioned – almost a justification that the tragedy befalling his characters is, in a sense, a necessary one. Having been so swept up in it all for long enough by now, you might argue that Visconti wants to be sure we haven’t forgotten this, but I’d argue that Visconti wants us to be sure that he himself hasn’t forgotten it.

I find these details to be tangential, and while the implications of the film’s politics are present, they aren’t pressing. They fill out the background, and fill in our understanding, but do so without obfuscating our view of the Prince, who Visconti is careful to keep the world revolving around. It is time, and man’s inability to reckon with time, and all the changes that time brings, that’s at the heart of the Prince’s journey. It isn’t about the nature of these specific changes, but the nature of change itself. As Martin Scorsese puts it, “time itself is the protagonist”.

‘The Leopard’ is a moveable feast. It has immeasurable depth, and trying to find your footing at the bottom proves about as futile as a chocolate teapot. It asks a lot of questions, without promising us every answer; revealing itself with ambiguity. But it does so in earnest, because there’s so much we don’t know, and sometimes there just aren’t any answers. That we might each take something from it, construing its values and interpreting its themes differently, is a testament to its power. With all that said – to those declarations of Marxist espousing, or right-wing touting, or questions arising around Tancredi as the film’s true centre, I would answer in adamance that you’re missing the point. But, if it isn’t about this, and it isn’t about that, then what is it about?

Seemingly, at least it seemed to me walking back on that brisk January night, ‘The Leopard’ is a film about the Sicilian aristocracy, and the changes that rid them from their world. It’s a film about an extraordinary man, in an extraordinary time, the likes of which, it’s clear, we will never see again.

Though the myopic Prince is initially unperturbed about the oncoming wave of change, and what it might mean for his kind and his kin, once he witnesses the potential for power of men like the mayor, he suddenly sees himself standing in the way of history, and on the wrong side of its forward sweep. When Don Calogero, who was responsible for the rigged referendum in Donnafugata, shows up for dinner at the Prince’s summer palace without his wife, but with his daughter, the solution to a question of survival presents itself to the Prince. Much of the film henceforth, is spent arranging the terms of Tancredi and Angelica’s marriage; the Prince having sown his family’s star onto Tancredi, and hitching his wagon onto Angelica’s (and by extension, the mayor’s). What’s important is that the driving factor behind all the Prince’s decisions is preservation. Always, the question is ‘what must change so that everything can stay the same’. ‘The Leopard’ is a tender portrait of the Prince and his people; the tradition and the history that the Salinas represent. And, the story is about their struggle to hold out against the inexorability of time. Until it isn’t. By the time the ball comes around, the Prince’s questions have been answered, and ostensibly, his concerns have been quelled. He has picked his heir in Tancredi, and thrust him into the future, into the new Kingdom of Italy. By liberating it from those on the way down, and aligning it with they that’re on the way up, the Prince has rewritten his family’s destiny. Thus, the Leopard has his resolution, and so do we. Talking to Father Pirrone toward the beginning of the movie about the guarantee of immortality for the church, the Prince pleads that no such warranty will be written for his social class, and that “any palliative that offers us another hundred years is like an eternity”. With Angelica’s debut into society at the ball, and her success there together with Tancredi, the Prince has fixed it such that everything can stay the same. He has bought his hundred years, and in turn, he has received his eternity. But, with the ball showing no signs of slowing, the Prince starts to wonder what an eternity really means. It is here that the film starts to shift, away from the narrative, and into a fable far beyond that of such a simple fall from grace.

If tomorrow belongs to the jackals and sheep, then this is the end of the Prince and his epoch. The thought weighs heavily upon him, as much we understand it would. And, while the dawning of this certain kind of death, and his awakening to it, provides the film’s natural finish, Visconti lets the scene linger far beyond that of such a palatable conclusion. Over the course of the evening, the Prince comes to terms with the death of his world – understanding even, to some degree, that its demise is only evolutionary. But, with an end comes a new beginning, and as the night stretches into infinity, it is the thought of this new beginning that begins to plague the Prince’s mind. The beginning of what? While he recognises his role as the last of the leopards, it isn’t the idea of being the last of his kind that saddens him so, but the reality: that in a palazzo full of people, his people, the only people around whom he can truly feel at ease, he is a man who is thoroughly alone, a man out of place, and a man out of time. What could possibly be left for him after the last dance is over?

In perhaps the only conversation of the night that seems pertinent to the Prince, he tells Angelica and Tancredi how he “often think[s] about death. The idea doesn’t frighten me. You young people can’t understand. To you, death doesn’t exist. It’s something that happens to others”. From his contemplation over the painting hung up in the host’s library, Death of the Just Man, we know that his mortality is on his mind, and from his rather frank comments about it we know that he knows it too. But, from his conversation with the young lovers, we can read a most revealing insight into the Price’s suffering, one that he himself mightn’t yet be aware of – one more complexed than a mere matter of mortality. In fact, it’s only in death (which he later refers to as the ‘perennial certitude’) that the Prince finds true solace. It is then, rather, in the here and now, in the time he will have to wait for the constellations to grant him his ultimate consolation, that the Prince feels irrevocably lost. As he walks back over to the painting, the Prince remarks to them both that “we must make some repairs to the family tomb”. The couple, whose eyes follow the Prince’s, turn first from amused to confused, and then to concerned. While he is clearly in distress, such comments made to his nephew and soon-to-be niece are no remedy for his affliction, and the Prince surely knows it. It is quietly jarring, and feels very out of touch with the otherwise strong, stoic, and share-no-burden personality of the Prince’s. (So much so, that it has received a rather awkward laugh from an audience on more than one occasion.) Though Tancredi and Angelica might see their ‘father’ speaking so matter-of-factly about his death as a sign of his strength, to us, it comes across a quiet cry of desperation. He is trying, and succeeding, to frighten the young couple, adopting a cruelly condescending attitude in the process, because he himself is frightened. Don Fabrizio is forty five, and while he may adopt the role of the elderly statesman with one foot in the grave, there isn’t anyone, neither among us nor among him, who would agree with his self-diagnosis. Frankly, I don’t think he believes it either. If we reference the book (which naturally we shouldn’t, though it helps here to prove a point), then we know that the Prince has more than a short while left until he kicks the bucket – about thirty years to be precise. Tired though he may be, he is a long way away from the big sleep, far further away then he’d have us believe. But, what’s telling in all this is that, whether it’ll be tomorrow or in another thirty years, he sees his next step as his last one. All that is left to be lived between now and then, he sees only as a formality, as another kind of ritual; one that must be carried out, simply because it must. Where he once looked out from his ancestral shores and saw the sky blue waters of the Mediterranean, he looks now into a great plain of emptiness, stretching into and beyond his horizon.

The ballroom scene seems to mimic a lifetime, dragging on for his eternity, and we wonder whether the rest of his nights will be spent like this; a relic among ruins, edging closer to extinction, before time swallows him up for good. He is the captain onboard this sinking ship, and so down he’ll go with it, but it isn’t the sempiternity spent at the bottom of the sea that scares the Prince, but the sinking itself; and it sinks so slowly, so he must wait patiently, and reluctantly, remaining so utterly powerless in preventing it. Like the water that rots the wood, the time will decay his spirit until, eventually, finally, the ship will go under, and he along with it, for all aboard to be subsumed by the sea. All the choices he’s made, all that he’s fought for, the life he has lived and everything he’s believed in; a whole chapter of history, out it will go, like the lights at the end of the night, and not with the leopard’s territorial roar, but in a docile and defeated whimper.

Filmmakers often say that the greatest moments come out of the audience’s own imagination. That, if you give them the pencil & the paper, and get out of the way, they will draw their own conclusions. German born Hollywood director, Ernst Lubitsch, was the unmitigated master of this – often letting entire scenes play out behind closed doors (while keeping the camera on the door itself; Mary Pickford once called him “a director of doors”), so that each viewer brought their own experience, taste, and sensibility in conjuring up pictures of what was going on behind them. It requires the audience’s participation, but the result is uniquely personal to each member. It is an irreplaceable tool in the director’s arsenal, that has since been replaced by today’s standard of showing every single thing in close-up… but we won’t open that can of worms just now. In the days of the code (when anything graphic was prohibited), it was frequently used to fill in gaps for the more carnal desires. In less salacious scenes, this technique was often used in lieu of violence, whereby we hear but don’t see, and are left to imagine what he is doing to her, as per Lean’s famous example in ‘Oliver Twist’. Either that, or it was used to reap fertile comedic ground, à la Lubitsch, as per any one of his movies. Visconti, however, employs the same device to explore the Prince’s mental state, or, more accurately, he uses it to get us to explore it.

In the fourteen months I’d been apart from ‘The Leopard’, what I remembered most vividly was the Prince alone at the ball. When we find him sunk into the library’s chestnut chesterfield, at the mercy of his wavering strength, for example; or, as he stands, shrivelling at the mirror in the men’s room, the tears swelling in his eyes. These are the moments that I kept seeing in my mind. I could’ve… I would’ve sworn that the ballroom scene was really the Prince’s scene, that the ball was in the background. In actuality, the reverse is true, and these memories were but a rosey figment of my imagination. It is our time spent alone with the Prince, that in fact feels like an interruption of the ball. But we feel him throughout the duration of the scene, no matter where we are. We start to look and to listen through the Prince, relating even the most innocuous of conversations back to him, even when he isn’t with us. Visconti merely sets the stage for the Prince and his thoughts, and lets everything but the ball play out in our minds. Entire sequences begin and end with him nowhere to be found – his own ‘scene’ playing out behind the proverbial closed doors. What is the Prince thinking? When we’re with him there is, bar the aforementioned conversation with Tancredi and Angelica, little to no dialogue. When we’re elsewhere, the conversations are trifling, and provide a pure counterpoint to the Prince’s silence.

The ball, the dress, the palace and the people; what once was elegant and sensual, now seems cheap and decadent. And, the more the night runs on, the less frequently we come back to the Prince, as though he is being drowned out; suffocated by all that he’s held dear. Each time we return to him we see a slightly different person. About his life he is uncertain, of both that which he’s lived and that which remains, and as he seems ill-equipped to deal with this resounding uncertainty, he feels irrecoverably weakened; and with no way out, he finds himself irretrievably lost. When he slips from Tancredi’s grip at the end of the ball, preferring to journey to the end of the night alone, we see a Prince without vitality, and more crushingly, without hope. In the dying moments, having shared his last utterance with the stars, having watched him walk away from the rising sun and into the darkened alley, we know that he is defeated. But, defeated by what? Or, by whom? We know that there’re questions to ask, but we must look within ourselves, and offer our own answers about life: what it means, what’s important and what isn’t; what, if anything, really matters? What is left for him? Is this his destiny? Was it always? Whichever way we choose to look at it, the Prince is trapped: by his choices, by his circumstances, by his time; trapped by his nature and trapped by his nurture. As we leave him for the last time we see him much like the movie’s maker, and the Prince’s original creator, as a man destined to forever wander between the winds.

Every one of the film’s first hundred-and-forty minutes lead us towards its final forty five – the Prince fighting the great fight, and losing it. What the nature of that fight is, depends on the person who watches it. It is a personal experience, and the power of the film is that the particulars of the Prince’s plight are unique to each viewer. It exercises our own character, and we find ourselves asking the questions that trouble us most. No matter what it is one’s going through, you can paste yourself onto the Prince. It is impossible to walk through life winning each and every battle, and, eventually, we must resign ourselves to loss, be it of a person, a place, or a moment in time. Beauty fades, memories fade, love fades, and time trumps us all. To accept defeat with decency, as per the Prince, is surely something we should strive for. If we are born without grace, and spend our lives in acquisition of it, it is only so that we can die with dignity. In this way, the Prince is our shepherd, a father figure who shines the light forward. His stakes might seem a little higher, but, ultimately his battle is against the allied force of time and change – the common alliance that will undo us all. To see such a great man, as much aspirational as he seems infallible, someone who we might all look to for guidance, forced to resign to his defeat, is truly affecting. We all remember the shattering moment when we first realised, as children, that our parents aren’t superheroes, that they too have flaws, weaknesses; that they too struggle, and suffer; they too bleed, will cry, or one day die. The closing of ‘The Leopard’ harkens back to that very same moment, while putting this great man into the context of our world, and its history; of yesterday, and tomorrow; deciding, ultimately, that he will never be more than he is today.

It would seem there is a lot to say about ’The Leopard’, which is hardly surprising, given that it has a great deal to say about us. From the outside looking in, it might seem intimidating, or unapproachable, and it is, in a sense, a little like a shot of hard liquor. Certainly, with its three hour run time, its period setting, and its specific historical context, it ain’t no fruity cocktail. Still, take the slug. I promise you you won’t regret it. (And if you’re already a single slug deep, then sit back, take another, and let the bottle lead the way.) All great works of art, those pictures, paintings, poems and books that our little earthly race can be proud of, can seem daunting at first. But, it is these works that remind us what it means to be human, what it means to be alive, and what it is that makes life worth living. And, ‘The Leopard’, for all its sometimes plodding plot line, and comically poor Italian dubbing, is no different. What the movie has to offer is unlike anything in the entirety of picture history and, to that end, it stands entirely alone, in a realm that reaches far beyond the four walls of the cinema. It manages to be so particular about its time and place, yet so profoundly personal, and still unanimously universal. It would be easy to think that such a film is out of step with the trials and tribulations of the world today, but by putting forth such unavoidably human questions, it ceases to exist inside of any context; it changes as we do, as much elusive as it is dynamic; an endless well on the meaning of humanity. Such a moving meditation on the nature of change, and time, in any medium that art has to offer, I have yet to find. Perhaps it is time, and only time, that’s required of us just to grasp at its greatness. If it was Socrates who said that, “The more I know, the more I realise I know nothing”, then I can humbly confess that, the more I see ‘The Leopard’, the more I realise I haven’t, really, seen ‘The Leopard’. Maybe, just maybe, one of these days, there’ll come a time when I can say I’ve finally ticked it off the list. Until then, drink up, ‘Cin Cin’, and here’s looking at you, kid.

You may also like

Time Waits For No One

Tellus integer feugiat scelerisque varius. Sit amet volutpat consequat mauris nunc congue nisi. At u

The Greatest Shot in Film

Preface What is the greatest shot in film? Aside from being a hard question with an ea

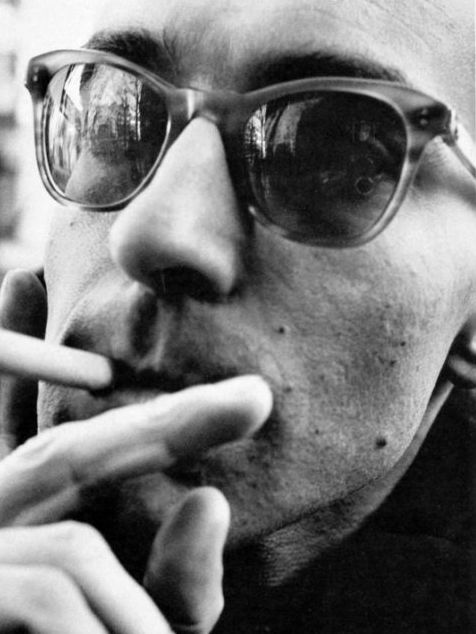

THE RENEGADE: JEAN-LUC GODARD

“I know nothing of life except through the cinema.” Jean-Luc Godard is a popular topic w

Post a comment