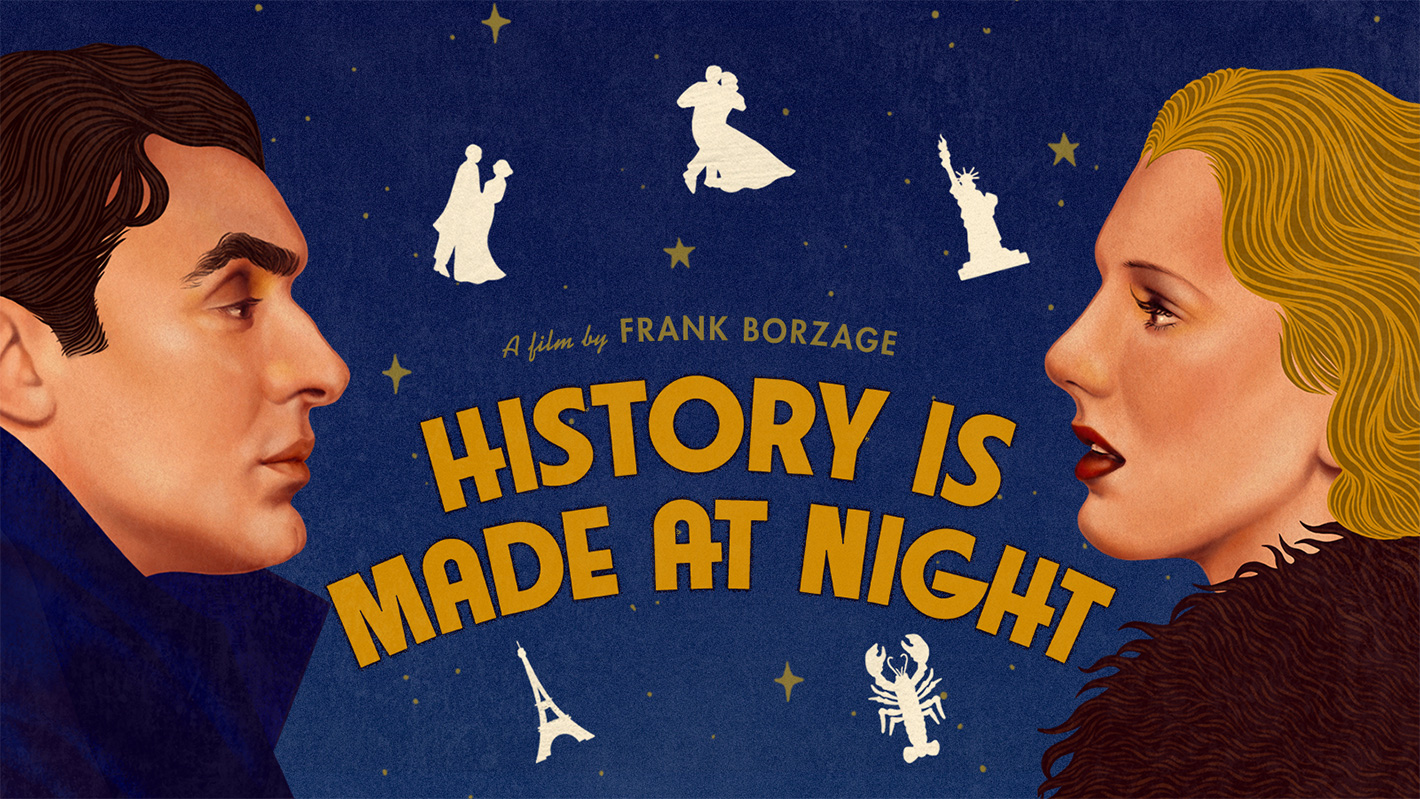

A LOVE FOR ALL TIME: FEBRUARY

“I don’t want you to go away. I just said that. You go if you want to.

But hurry right back. Why, darling, I don’t live at all when I’m not with you.”

– Ernest Hemingway

There’s a moment at the tail end of ‘History Is Made at Night’, when our two leads are forced to make a choice. It’s a choice that will call into question the strength of their love, and their respective decisions may forever undo that which they’ve spent a whole film fighting for. And, in a most Hollywood of ‘endings’, he does the right thing and she does the right thing and they’ll be together and we get it – they’re in love. They’ve proven it to themselves, to us and to each other, and everyone’s a winner. But, director Borzage isn’t through with us just yet: after we dissolve, briefly away from our lovers, and back to them again, we find them sitting alone, together, talking of their pasts, of their lives before destinies crossed paths; lives lived without the other, lives that matter no more, not now that they’ve one another. As they sit, gazing into each other’s eyes, as much in earnest as in innocence, ‘History’ reaches an emotional climax that life itself could scarcely eclipse.

For second generation American, Frank Borzage (pronounced Bor-zay-gie), there was no greater theme than love. Often relegated to the title of ‘romanticist’, Borzage’s films celebrate love as life’s only through line for his collection of lost souls. With Frank, love was a religion, and in finding it, his characters found the power to transcend their earthly circumstances. But, where many directors might pussyfoot around the truth for fear of stumbling into the saccharine, Borzage pirouettes right into the deep end with the conviction of someone who not only revered his material, but believed in each and every word.

As a result, one doesn’t root for Borzage’s leads just because we care about him, her, or them together. As in much of his filmography, ‘rooting’ for ‘History’’’s Paul & Irene is, really, rooting for love itself; rooting for love to triumph over circumstance, to triumph over probability, and in the particular case of ‘History Is Made at Night’, to triumph over genre. But, for the first two or three minutes, the film settles into fairly familiar territory…

She, Irene (played by Jean Arthur), is married to Colin Clive – a possessive and plutocratic shipbuilder. A contemptuous man with more than his fair share of forehead, a man whose paranoia and jealousy have driven away the one thing neither his money nor influence can buy back: Irene. After she files for divorce and flees for Paris, Clive concocts a plan to trap her, for good, in their loveless marriage. Erroneously convinced that Irene divides her down time between a string of other men, Clive decides to play her ‘own’ game against her, and pays off the chauffeur to force himself upon Irene. When he and his private dick catch them in the act, Clive will obtain legal grounds upon which to prevent the divorce. So far so good.

That very same night in the Hotel Triumph, an unknown man overhears the ‘tryst’ going on in Irene’s room and, turning down his hat and up his coat collar, he slips out onto the balcony and into her room. Defending Irene against the chauffeur’s unwanted advances, a struggle ensues between the two men. Clive and his shamus burst in, expecting to find Irene and the chauffeur in a compromising position, and instead find themselves in one. With Michael the chauffeur out cold on the floor, and the man pointing at them with a gun, Clive & Co wind up locked inside the dressing room. The man then steals Irene’s jewels, steals Irene’s fur coat, and then steals Irene.

In the back of the ‘getaway’ cab, going nowhere fast, the man offers Irene a cigarette, returning her jewellery, and revealing his identity. It is, of course, Paul Dumond (played by Charles Boyer) and, putting his friend to bed in the room next door he happened to overhear the scene going on in Irene’s room. Of course, if he didn’t make believe that he was a thief then his presence would’ve compromised her as much as chauffeur Michael’s, and he only kidnapped her so that he could return the stolen jewels. Together, they conclude that Irene needs to have a think before she heads back to her hotel to face the music. Naturally, Paul knows where to get the best champagne in Paris, and perhaps a drink would help her think. Would she care to join him? She would, of course.

They arrive just in time to catch head chef, ‘The Great Cesare’, and the Chateau Bleu’s band heading home after a long days work. To the world they are closed, but for a couple compliments and champagne for all, Paul buys Irene the night. This, they dance away, and in the most romantic, and intimate scene in cinema, they fall irrevocably in love.

But before either we, Paul, or Irene can find our footing and settle into the picture’s new direction, the ground again starts to shift, and Borzage pulls the rug right out from under us. It’s a magic carpet that will take Irene away from Paul, away from us and away from Paris, where we will stay… for now. But if anyone can bridge the gap across the Atlantic, or swim the sea of reasons why the two can’t be together, it’s Paul Dumond, as played by Charles Boyer. In a most characteristic ‘Boyer’ role, Paul is the classically American ideal, of the suave and sophisticated European gentleman. In his confident flirtations with Irene, familial relations with Cesare (the ‘World’s Greatest Chef’), and knowledge of all things from pink cap champagne, to tango, and even how to mix the chiffonade salad’s dressing – Paul is the depression-era’s most archetypal leading man. But even Paul, a man with all the answers, with always the right thing to say at the right time, a man whom we recognise, and trust, in whose company we can feel comfortable and at ease, has a rug of his own to pull. It is only the following day, when Paul returns to the Chateau Bleu, strolling straight into the kitchen, swapping his blazer for a dinner jacket and scribbling the day’s plat du jour on the menu board, that we finally see the movie’s set-up clearly. Paul is not Boyer’s typical, smooth talking big shot, but in fact merely the restaurant’s waiter. Not for the first time, nor the last, our expectations are thwarted. Not bad, for what feels like the first five minutes.

What follows is a patchwork quilt of genres, a real melee of tropes and conventions. But, binding it together – all the zany and bizarre, twists & turns of plot and story that the picture (somehow) follows – is its central romance, and its unabashedly Borzagian theme.

When principal photography on ‘History’ began, in November 1936, Borzage had little more than the movies’ title to go by. Screenwriters Gene Towne, Vincent Lawrence and David Hertz, working on different scenes to varying degrees, delivered each chunk of the script straight to set each morning. Even the films’ famous maritime climax was a last minute idea, courtesy of producer Walter Wanger, who wanted to make use of a new steamship miniature he’d had built for Christmas. This approach, while unorthodox, wasn’t hugely uncommon at the time. With the studios churning out films like the Greeks do yoghurt, there wasn’t always time to prepare each picture properly. And while some movies managed to survive an entire lack of preproduction, more often than not it was to the picture’s detriment.

That ‘History Is Made at Night’ didn’t suffer the same fate seems, on the surface, a remarkable stroke of luck – the likes of which could only be attributed to the so-called movie Gods. However, I’d argue that there are three, slightly more tangible, but no less ethereal parties responsible, for turning the tides of ‘History’’s ship. A ship which, surely, at one point in time must’ve looked like it was headed for disaster.

The importance of director Frank Borzage, whose reputation has suffered terribly at the mercy of time, can hardly be overstated. While not considered his crowning achievement by some, critic Andrew Sarris put it justly when he called the movie, ‘not only the most romantic title in the history of cinema, but also a profound expression of Borzage’s commitment to love over probability’. In the hands of any other director, ‘History’ could quite easily have been a fun, zany screwball comedy but, ultimately, an overly improbable fable of love in the face of great odds; a tale too ludicrous to ever engage us ‘seriously’, and thus emotionally. But, while saving such a story from sinking into the sentimental is no mean feat, a feat to which Borzage was no stranger, it is impossible to overstate the role of our two loving leads. Really, it is actors Jean Arthur and Charles Boyer, who take to task this unforgivably preposterous premise, and turn it into cinema’s most moving, honest, and brilliant portrait of love between two people.

For every thousand screen loves, there might be one like Paul and Irene’s. When so many picture pairings rely on intellectual exercises to prove the pair’s love to us, the audience, theirs dares to offer us nothing concrete. It isn’t that he’s all this, but isn’t that; that she has this, but doesn’t have that. Nor is it that they undergo the routine lover’s arc of fighting and then falling. Neither have to give up parts of themselves to gain the trust, nor the love of the other. Right from Irene’s very first ‘Oh’, of which there are several (“All I can seem to say is ‘oh’”), in the back of the taxi heading to the Chateau Bleu, it is clear that each has met their match. With her American forthrightness, her utter lack of pretension, and his elegant theatricality mixed with a masculine spark, the two find equilibrium: equal parts comfort and challenge. Their chemistry is as much easy as it is erotic, and right from the jump, the two move in sync. But, to try and analyse how, or why it works, is an exercise in futility – the magic is well and truly up there on the screen, for all to see. While their words are full with the emotions they feel, it is in the looks shared between them, that we feel it too. And, never, neither before nor since, have I felt a love the way that I feel theirs.

It’s been said that a movie without a romance, isn’t a movie – it’s a film. It isn’t better, nor necessarily worse, it’s just different. But, whatever you’d call it, if we can agree that it isn’t a movie, then we can agree that Frank Borzage may stand as cinema’s foremost moviemaker. His unwavering belief in the power of love make his movies as universal, and affecting today, as ever. And while such important feelings as fun, and surprise, are as present on first watch as fifth, ‘History Is Made at Night’, stands as Borzage’s greatest gift.

Movies like ‘History’, prove the silver screen’s ability to deepen our feeling, engage our emotions, and reveal truths that we mightn’t otherwise. Either that, or it’s proof that in art, we find the lies that real life promised. Either way, it’s my movie of the month for February, and will be till I haven’t any Februaries left.

Of all the romances, on all the screens, in all the towns, in all the world… this one’s the one for me.

You may also like

A REMEMBRANCE OF THINGS PAST: MARCH

“We were the Leopards, the Lions, those who’ll take our place will be jackals, hyaenas;

A MAN & HIS MACHINE: JANUARY

“When you’re racing, it’s life. Anything that happens before or after is just wa

A TALE AS OLD AS TIME: JULY

‘Intolerance: Love’s Struggle Through the Ages’ has long been a white whale of mine w

Post a comment