A MAN & HIS MACHINE: JANUARY

“When you’re racing, it’s life.

Anything that happens before or after is just waiting.”

The label of ‘flawed masterpiece’ is a curious one. Although romantic in nature and revealing of its label maker, given that the crowning of a masterpiece is more binary than sliding scale, it is surely a fallacious notion. Or so I thought.

Steve McQueen’s ‘Le Mans’ is the story of one man, and one race. Both its magic, and its mystery, lie in that very fact – that the film offers us nothing, nothing at all, except the shotgun seat in Steve’s cockpit. But besides the exhilarating experience of driving two hundred miles-per-hour in a Porsche branded petrol guzzler in & around the French countryside, ‘Le Mans’ stands as a tribute to McQueen’s unwavering love for motorsports, and does so at the expense of a functioning movie.

The film opens with, well, Mr. McQueen driving. After a burst of contemplative cuts, zooms, and flashbacks, we understand that McQueen’s character, Delaney, was involved in a fatal crash in a prior Le Mans. But before either of us have time to reflect, the credits roll, and the preparations for this years race begin. Then the drivers preparations begin. Then the race begins. Too fast and furious to be transcendental – the effect is the same, and you’ll be nearly forty minutes in before you realise you only just heard the first line of dialogue. It is with this ceaselessness that the film will drive, remorselessly forward, for the next hundred or so minutes.

With regards to plot, there is very little else worth mentioning. Obviously, since the film revolves around a race, a narrative will be built in around the winning or losing of it. Curiously enough, however, while the race’s end is the film’s natural climax, it’s really just a MacGuffin. Unlike any other picture shot out on the track, ‘Le Mans’ relies on neither metaphor nor allegory for its thrills, rather, it relies only on the racing. People’ll tell you that listening to somebody talk about something they love is interesting. While I’ve found that to be somewhat of an overstatement, what I will say is this: watching someone do something they love is an entirely different kettle of fish. And when that something is racing, and that someone is Steve McQueen, the result is positively riveting. And that, is an understatement.

Why it works so well, is twofold. Firstly, the audio-visual nature of motorcar racing is perfectly suited to the cinema. The fact of racing itself, is of course, entirely visual. So long as we (the camera) are close enough to discern between cars, but not too close to blur, then the race’s inherent narrative is clear. The film’s emotion comes from the cutting, and the audio. The guttural growl of a Porsche 917K’s engine is enough to make even the most pro-pedestrianiser’s adrenaline rush. Witnessing the part dance, part combat between these grossly overpowered man-made death-cages, and listening to them respond like wild animals out only for each other’s hide, is a brilliantly cinematic experience. I daresay, one you couldn’t even replicate if you were there in person. And what ‘Le Mans’ does that no other racing picture dares, is leave it all out on the track. The movie’s title is not symbolic, and the race itself is no grand metaphor – it is all about the driving. Any cross-cutting between the driver’s life in and outside of the car, or allusions to McQueen’s mind drifting off to matters of love or life are totally absent here, and our focus is exactly where the drivers’ must be. Even the obligatory shots of a car’s speedometer are missing; the shot choices and sequence montaging are purely emotional.

Whether this approach was intended or not, remains unclear. Certainly, McQueen’s own aims had been to make the definitive movie about racing, and wanted to translate the feeling of racing to audiences – which leads one to believe this it was certainly his intention (this is corroborated by McQueen’s refusal to star in 1966’s ‘Grand Prix’, which saw much greater acclaim, but which the actor felt was inauthentic). Though, after a string of writers were attached and detached as the production spiralled out of control, it is clear that the studio grew increasingly concerned with this, essentially plotless, star vehicle that hadn’t even a love story as a sub-subplot, and forced some last minute changes. Ultimately, the final film is a failed attempt at the latter, with faint whispers of a romance and a few incongruous cries that question a driver’s morality, the likes of which are unresolved and feel rather half baked. It’s hardly surprising, then, that the film was panned upon its release at the start of the seventies. As a ‘Hollywood’ film, ‘Le Mans’ is a failure. The basic elements of plot, character, and storytelling are about as present as a bicycle on a racetrack. But as a bizarre mix of documentary footage, experimental film and transcendental style all wound together by the pull of a major Hollywood star, the film is an inimitable success.

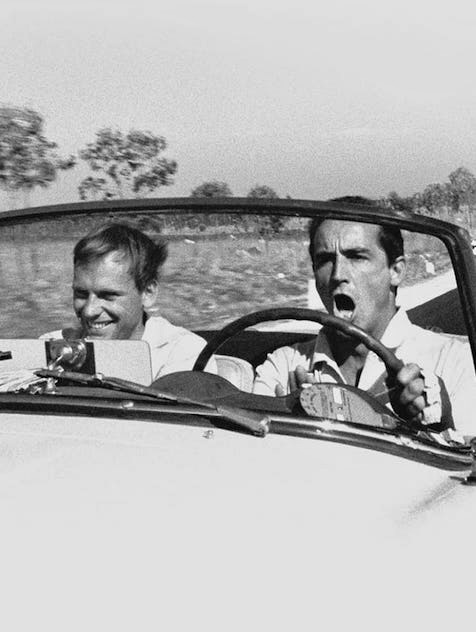

Thus, the second and most undeniable reason behind this films curious mastery is, of course, the “King of Cool” himself. Never has the magnetism of a star been so clearly felt, as it is here, with McQueen’s characterisation of Delaney. His is a character with less lines of dialogue than there are names of stunt drivers in the credits. He has no ties to anyone, nor anything, outside of the circuit, and his motives for re-risking life and limb are never explored. Delaney is a man whose past looks just like his future, and the Delaney we meet at the start hasn’t changed a measly ounce from the Delaney we see at the race’s finish. It isn’t even the winning that seems to drive him, but more so the need just to beat his Ferrari-racing rival. Is it a personal vendetta? Do they have some kind of history? We’ll never know. The implications of the crash he was involved in the year before – in which the other man was killed – is also, neither explored nor resolved. All we’re left with is a man who spends much of the film’s runtime driving, and the remainder of its runtime regretting that he isn’t. But when the man is a Steve McQueen that’s about as Steve McQueen as Steve McQueen gets, giving it every bit of his heart and soul, you have a man that is endlessly fascinating, and impossibly watchable. No amount of drama school experience, or ‘range’ as an actor, could demand your attention quite like he does. That, is what you call star power.

It remains widely known that motor racing was the actor’s true love, and certainly, it helps his ‘performance’ to no end. He drove cars in his most famous films, and spent his days off set entering races around the country. In fact, the entire production of ‘Le Mans’ was all his doing.

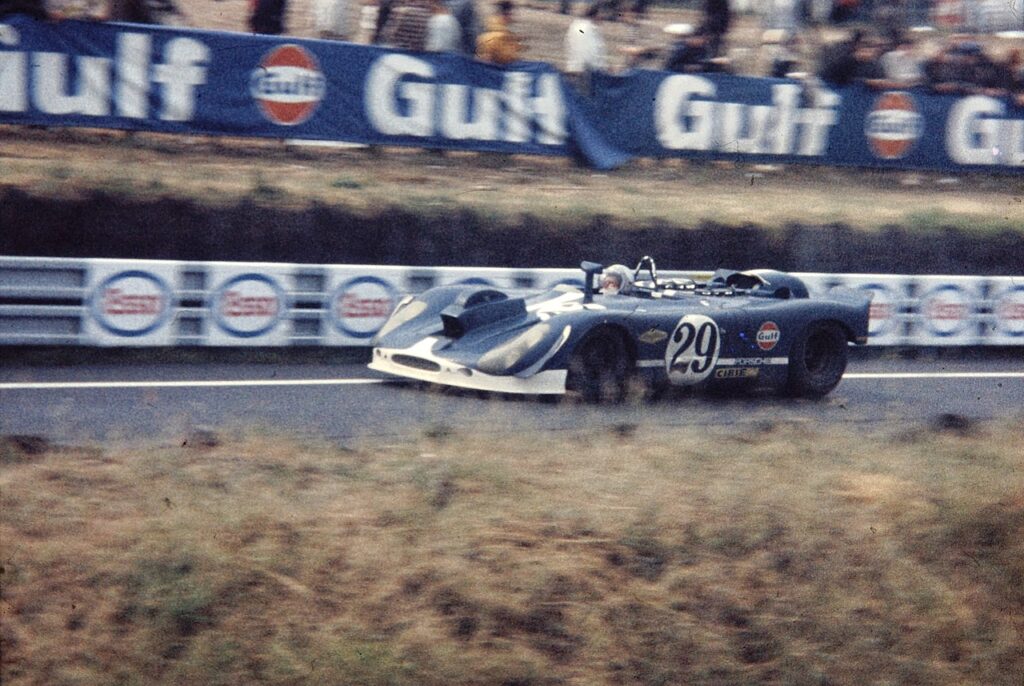

Regrettably, it’s the battle he fought making the film that’s largely come to overshadow the film itself. Years of struggling through preproduction, the director quitting halfway through shooting, two car crashes (including one for Steve), three editors and more writers than is healthy to have on one single picture… It was a tremendous undertaking – one which saw McQueen’s production company, Solar, actually enter a camera-rigged car into the 1970 Le Mans to capture real race footage (pictured left), and end up finishing ninth. But by its end, McQueen had signed away both his actor’s fee and his percentage of the profits, in order to keep the production funded, and ultimately relinquished the creative control he so dearly craved.

The common wisdom is that, thanks to McQueen’s unwavering passion and commitment to the project, the film still works in spite of itself. That is, in spite of its lack of plot, character development, etc. While it’s true that it lacks the sense of completion, or emotional fulfilment that we’ve long come to expect as a moviegoing public, somehow, it still works. For me, however, it works because of itself. It doesn’t aspire to a standard Hollywood story, because it isn’t one. It isn’t a film about a man like you or me, nor a woman for that matter, it’s about a man whose obsession is both totally unceasing and cruelly uncompromising. I don’t believe for a second, that any driver racing Le Mans, would have anything else on his mind for the race’s twenty four hour duration. So why would the movie? McQueen set out to make a movie about racing, not a movie about life or love or loss. And so, the movie’s about racing. It only takes for granted that an audience member mightn’t be as taken by motorcar racing as its makers, because it knows that by its end, you will.

What makes the seemingly impossible task, of drawing our eyes and emotions determinedly towards these inanimate objects possible, is Steve McQueen: who neither wrote, directed, nor produced ‘Le Mans’ – but never in the history of the moving image was so much owed by one movie, to one man.

Is it a masterpiece? I cannot, in good conscience, tell you that it is. But the result of combining Steve McQueen and a movie about racing is one that, against all its odds, works about as brilliantly as a pair of telepathic twins on a tandem.

You may also like

A ROAD OF NO RETURN: MAY

In life, it often is said, there’re two types of people. On the one hand,

A GANGSTER’S PARADISE: JUNE

“A cartoonist’s only commandment should be: Thou shalt not bore.” – Tex Aver

A REMEMBRANCE OF THINGS PAST, PART II: APRIL

“I live with this movie every day of my life.” – Martin Scorsese Imagine

Post a comment