THE BIG SLEEP: PROGRAMME NOTE

“Nice state of affairs when a man

has to indulge his vices by proxy.”

Audiences attending this 1946 film noir classic, ’The Big Sleep’, off the back of Raymond Chandler’s novel, will likely be disappointed – in it they will not find the Phillip Marlowe that Chandler penned so poetically. Similarly, those in search of classic screen-team scenes of Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, may even feel a little underwhelmed. While the film’s two leads produce some of its most memorable moments, tensions between the two never quite reached the heights of the couple’s first outing, two years earlier. Fans of film noir coming to it via the dark alley from whence they came are, also, at risk of possibly coming away a little let down. The concoction of stifling pessimism and ceaseless claustrophobia which underpin the decade’s darkest noirs, is seldom present here. While we do have a hero confronting corruption and the most wayward of moral degenerates, and a film with all the hallmarks of America’s murkiest genre, it is far from the genuine article. When asked if ‘The Big Sleep’ was not almost a parody of detective movies, with all the women making passes at Bogart, director Howard Hawks replied, “Oh yeah, we were just having fun”. Those in search of that, will find here, exactly what they’ve long been looking for.

Both fans and detractors alike, a scale which is unevenly balanced, will likely draw attention to the plots’ nonsensity, and many will quote the famous anecdote whereby neither Bogart, nor Hawks, nor even Chandler, knew the identity of the Sternwood chauffeur’s murderer. (When quizzed by the director, the novelist admitted, “Dammit, I didn’t know either”.) And while it makes for great movie trivia, it is often a weapon which both sides utilise, either to attack or defend the films’ greatness, a greatness which lies well outside the realms of plot mechanics. The only spoiler alert necessary is: don’t try to keep up with who killed who, why, nor who’s got what over who, and why they’ve gone to such lengths to hide it.

Raymond Chandler’s novel of the same name, published in 1939, was considered relatively un-filmable, given the confines of the Hays Code. Arthur Geiger, Marlowe’s initial lead, deals in pornography; Carmen Sternwood is seen more often naked than not; and there is reference to homosexuality, which explicit mention of was prohibited by the code. Hawks, an avid reader of the novelist, saw it as the perfect follow up to Bogie and Bacall’s star making turn in 1944’s, ‘To Have and Have Not’, and persevered, along with a trio of writers. At the time of its release, it was the second of Chandler’s books to be silver screened, and the second iteration of his immortal private eye: Phillip Marlowe. Whether or not Bogart’s is the truest interpretation of Hollywood’s native shamus is up for debate. With his world weariness, his tired pair of eyes that have seen it all a dozen times over, Bogart certainly embodies the spirit of a detective. Unlike Marlowe, however, Bogart isn’t one to blunder, and he plays the role similarly to that of the hero in ‘The Maltese Falcon’, a role Bogart had by now made his own. The Marlowe of the page often has to stumble his way towards the truth, and sometimes sit in the background to let the truth reveal itself – a slightly different size of shoe that audiences then were used to seeing Bogie tail a suspect in. (For stricter adherence to Chandler’s prose, and Marlowe’s wicked humour, see 1944’s ‘Murder, My Sweet’, ironically starring song and dance man, Dick Powell, in the Marlowe role). What we do have in Bogart’s Phillip Marlowe, is the fullest iteration of one of cinema’s most recognisable heroes – the cold but charming, tempted but infallible, private detective – a man alone, on our side of the law, willing to do it all by himself.

It was in the aforementioned adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s ‘To Have and Have Not’, also directed by Hawks, that Lauren Bacall was first introduced to audiences, and incidentally to Humphrey Bogart, too. Their affair on set led to the sparks on screen jumping right out into audiences – they wanted more, and Jack Warner determined that another onscreen pairing was needed, but quick. Production shortly commenced but difficulty with Bogart’s drinking, a backlog of war movies, and disagreements over certain scenes led to the film’s theatrical release only in the summer of ’46. During initial screenings the decision was made that Martha Vickers’ role as the younger of the Sternwood daughters, Carmen, was taking too much heat off of Bacall’s role as Vivian. What remains are mere embers of the fire that once blazed, and while it is Bogart’s cafe conversation with Bacall, riddled with double entendre, that endures as the prime example of circumventing censorship, the most sizzling sentiments fly between Marlowe and the younger of the Sternwood sisters. The released version commits to Bogie and Bacall’s coupling, throwing the spotlight on what audiences had really come to see: the girl, of twenty at the time, displaying greater insolence than the master of insolence himself, and thereby winning him over. But their’s is not a romance for the ages, and they never quite managed to match the chemistry captured in their first film together. In ‘The Big Sleep’, Vivian’s relationship to Marlowe sits somewhere in-between Noir necessity, the Femme Fatale, and the very non-noir trope, of boy meets girl, and boy gets her.

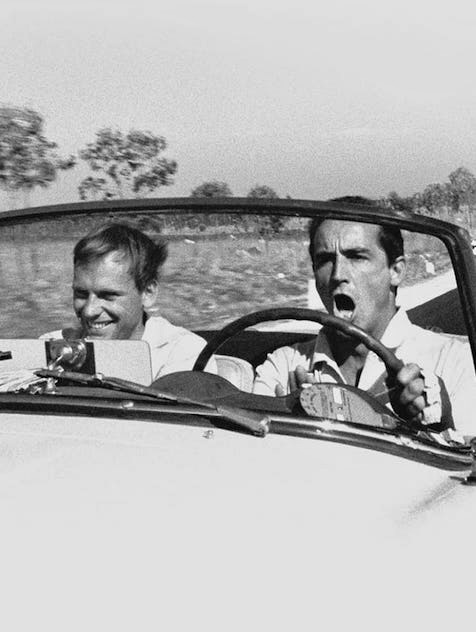

But Film Noir is a moveable feast, and what characterises it depends on who you ask. Ostensibly, ‘The Big Sleep’ fits easily within it, chiefly due to its origins in the hardboiled school of fiction. Though, where film noir can be characterised by its visual cues from German expressionism, its seedy streets connected by even seedier alleys, ’The Big Sleep’ plays out more often in large drawing rooms, and car interiors. The sets aren’t swimming in shadows, but lit in a more classical Hollywood style. If film noir began in the 1940s, and endured as the decade’s most emblematic genre then, as Newton would have it, the 1930’s was the decade of the romantic comedy, and more specifically, the screwball comedy. And if the screwball comedy can be characterised by comedic relief through ‘zany, fast paced & unusual events, sarcasm and screwy plot twists, fast-paced verbal duelling and witty sarcastic dialogue’, then Hawks’ film has a lot more to tell us. While the two genres may seem at odds, and in many ways they are, if we consider that Hawks not only helped pioneer the screwball comedy with 1934’s ‘The Twentieth Century’, but helped to solidify it with perhaps the genres most representative entry, 1938’s ‘Bringing Up Baby’, then the comparison seems a little less farfetched. And while there may be a lack of sight gags or out and out laughs, I defy anyone to hear Bogart tell General Sternwood than one of his daughters, Carmen, “tried to sit in my lap while I was standing up”, without cracking a smile. Marlowe may not be amused by the behaviour of the people in the world around him, but we sure are.

As with most of Howard Hawks’ movies, the plot is merely an excuse to hang out with some of the sharpest, slyest characters ever committed to celluloid. If you came for Phillip Marlowe, stay for Bogart’s eternal adaptation. If you came for crackling conversation between him and Bacall, stay for Bogie’s verbal sparring with, well, just about everyone. If you came for film noir, stay for the inexorable pace and a story that will twist and turn you gutter-wards. If you came for a good night at the movies, then stay for a great one. Questions such as who killed who, why did they kill them, or are we sure it wasn’t someone else – have no place here – they couldn’t matter less. The bodies pile up, the mystery compounds, and the answers seem never to surface. But in Bogart’s pocket at all times is a gun, and nestled in alongside it, we are sure to find out the truth.

Alec Rowe, June 2023