THE RENEGADE: JEAN-LUC GODARD

“I know nothing of life except through the cinema.”

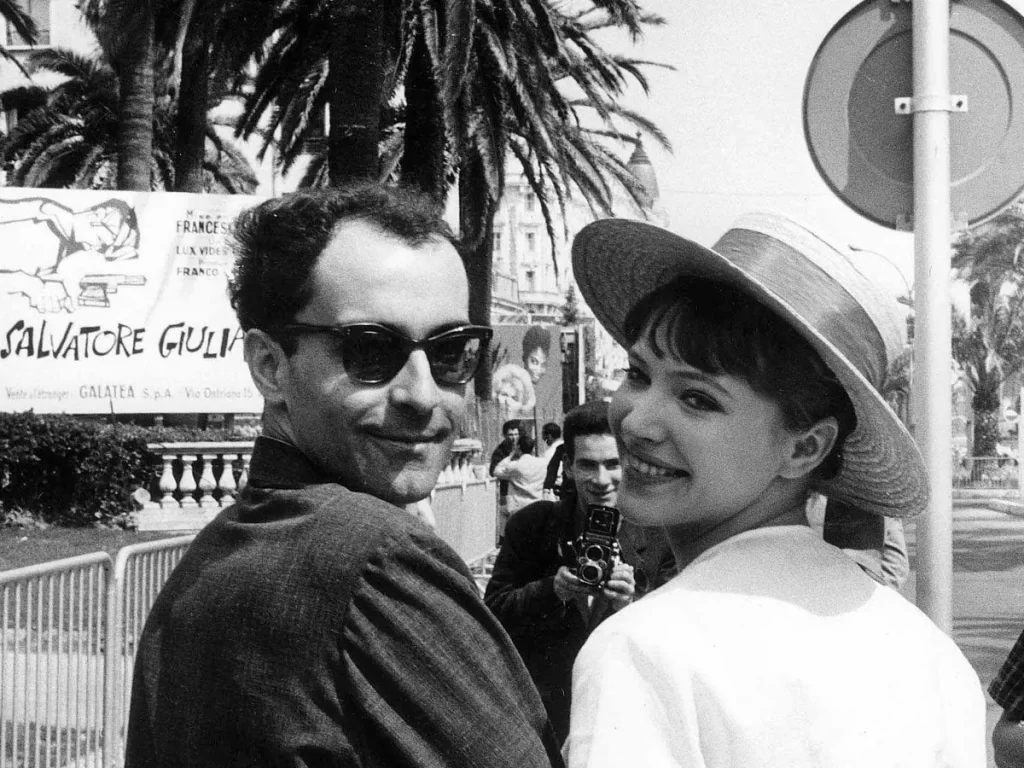

Jean-Luc Godard is a popular topic when it comes to film. His death, by assisted suicide, on Tuesday 13th September 2022, has sparked an influx of articles written about him and his work. Ever since he flicked ‘Breathless’ onto silver screens around the world with the end of his dying cigarette, Godard has been a constant figure in discussions on cinema. Even outside of film, his work continues to live on in popular culture: reproduced stills of Anna Karina and Jean-Paul Belmondo kissing over their cars in 1965’s ‘Pierrot le Fou’ and reprinted posters of his most piercing and permeating films still line the banks of the Seine & adorn the college hall walls of your ‘film-loving’ girlfriend. More than any other director of his generation, Godard’s name has become shorthand for cool even outside the realms of cinema. Within them, it is hard to understate his importance. As Voltaire once said of the fair man upstairs, “if God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him”, so too, where the art of the moving image is concerned, it would have been necessary to invent Jean-Luc Godard.

That is not to say that he is unanimously liked, nor even appreciated. While you may be hard pressed finding someone who’ll openly admit to disliking him, as with anyone held in such high regard, he has his detractors – and Godard more than most. I’ll confess, there are dozens of his 130-odd films that I’ve never watched, and frankly am unlikely to do so, and for reasons I shall address briefly further on, I find a number of those I have seen, unwatchable. With that being said, I’ll be damned if ever I’m caught questioning his genius. Without him, I may never have fallen so hard for the movies. And for that, I’m yet to decide as to whether I should love or loathe him.

Parisian born in 1930 to Swiss parents, Jean-Luc Godard came to cinema relatively late in life. It was only upon moving back to Paris, from Switzerland, to study Ethnology at the Sorbonne, that he too began to fall for the movies. Ditching class for dark screening rooms, Godard became involved in a crowd of young cinephiles who would centre themselves around well known critic and film theorist, Andre Bazin. The now famous, ‘Cahiers du Cinéma’ (a monthly film publication, still in print) started on the back its predecessor’s final issue, ‘Revue de Cinéma’, became the place where these film enthusiasts, (among them François Truffaut, Éric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol, and Godard himself) began writing articles for publish. Their harsh criticism of French films, alongside their championing many American directors would quickly cause quite the stir. That for which they are best remembered, since the majority of their controversial stances have now been adopted by the general consensus, is a theory they coined ‘politique des auteurs’. Put simply, auteur theory compared a movie’s director to the novel’s writer, giving the former as much responsibility and credit for a film, as the latter for his/her book.

To chop a long story short, after more than half a decade of writing and working for ‘Cahiers’, the young cineastes decided the time had come to start making movies themselves. And with that, the French New Wave began. Though, it wasn’t until 1958, with Chabrol’s drama ‘Le Beau Serge’, that the ball really got rolling. Critical and public approval of the film gave the group all the validation it needed to kick-start what was arguably to become the most influential film movement in history. What followed was Truffaut’s ‘Les Quatre Cents Coups’, which won Truffaut the best director award at Cannes – having had himself banned from the festival the year prior – and international prestige with it. The door was now wide open.

Godard, who by this point had little more than tried his hand at a few short films, and to no particular avail, decided he wasn’t here to stand outside in the cold and wet to watch the party through the windows. Back in Paris, he stole money from the ‘Cahiers’ safe, absconded with the funds and a treatment co-written by Truffaut, and set about making his first feature film. The other writers at the magazine, Truffaut included, caught up with him fairly quickly, and in true co-conspirator style, secured more financing for Godard such that he could make a better go of it. The result, was a little film called ‘A Bout de Souffle’, which directly translates to ‘Out of Breath’, but is known to all by the unshakeably sexier name, ‘Breathless’. I won’t touch on the movie here, because there are dozens of lectures, reviews, and books on it, should you care to take the time, and there is little to nothing more that I could add. All I shall say is that it is impossibly cool, possibly more alive today than either you or I, and for better or for worse, changed the course of movies. And so, Godard’s career as writer-critic turned filmmaker, began. Following swiftly on the tails of ‘Breathless’, Godard went on an unprecedented seven year streak during which he made twelve feature films – three of which feature in the top fifty of Sight & Sound’s 2012 list of ‘The 100 Greatest Films Ever Made’.

The word ‘iconoclast’ is often thrown around when it comes to the Swiss-French director. Shouts of, ‘with such-and-such film he tore apart the form’ can be heard from any dark corner of any given cinema. While referring to Godard as such seems cliche and old-hat by now, and while I don’t find it untrue, it certainly doesn’t do him any favours in my eyes. That Godard ‘shattered notions of what a film could be’ is something I have to contend with in spite of his genius. Not all, but many of the reasons for his canonisation, are things that positively affect my view of him as a director, but dampen the light I hold for his movies. By that I mean, on a list of cinema’s greatest directors, I’d rank him way up ahead, in a league of his own, and while the lessons one can learn from him are ceaseless, I don’t particularly like his movies. I would consider myself a purist, and a classicist; and both in equal measure. His disregard for convention is often admirable, but as frequently and equally insufferable. One of his most famous quotes that, ‘A story should have a beginning, a middle and an end, but not necessarily in that order’, is one ‘quirky’, ‘cool’, film-nerd maxim I have never found myself drawn to. I like a story to be told chronologically, with a strong three-act structure (which dates back to Aristotle), and a traditionally melodramatic climax before the final fade out suits me just fine. But for Godard, as time went on he played more and more with traditional narrative form, and film’s tried and tested conventions, resulting in many of his movies feeling disjointed, confusing, or just down right tedious. Adding salt to the wound is Godard’s frequent breaking of the forth wall, à la Bertolt Brecht, in order to break the illusion of ‘reality’ – one of my least favourite things that has ever been done, ever, in history. I watch films to be wholly consumed by them, for them to wash over me, and the more I drown in their waters, the more favourable I’m liable to feel about them. To have that spell broken by Anna Karina turning around and talking to me, ‘the audience’, borders on the fatally unforgivable side of filmic grievances. Granted, there are few people who could come so close to getting away with it as Anna Karina, but I remain firm in my stance, and I digress. I can appreciate these sleights of hand and I do not find it hard to view them contextual, and while it can be fun to watch all the rules being broken, ultimately they serve merely as reminders that many conventions, chiefly continuity devices and narrative structures, are standard practice for a reason.

With all that being said, to claim that Godard was a formative figure in my own personal journey on this earthly planet of ours, would be an understatement. In fact, it was during the height of my Godard-mania, a period all aspiring moviemakers go through, whereby his name seems just three letters too long, that the thought of making movies myself occurred to me for the very first time. This was partially due to the fact that he, like his New Wave cohorts, was little more than a well meaning amateur, one who just loved movies more than anything else. When he didn’t like what he saw and decided that he could do it better. And, in a move in which I naively saw myself, he did do it better. However, I find that amongst the myriad of literature and films about him, the aspect that drew me so strongly to Godard, the aspect that appealed to me so strongly it made me consider movies as more than just a hobby, is one seldom spoken of – the personality in Godard’s work. By that, I do not mean merely that his films have personality, but that they bear, quite unmistakably, his own personality.

To best articulate this, I will centre on Godard’s film from 1963, ‘Le Mépris’ (‘Contempt’), but before I get to that, a slice more context is necessary here. While casting for ‘Breathless’, Godard reached out to a young model he had seen in a soap commercial, for a small role in which she would appear naked. This name of the lady in question was Hanne Karin Bayer, and she refused, on the grounds that she would not appear in his film without her clothes on. Upon casting for his next film, ‘Le Petit Soldat’, Godard reached out once again to Ms. Bayer, this time for the leading role, a role in which she would appear at all times fully clad. This, she accepted. It was Coco Chanel who supposedly offered the young Dane some advice on picking a new name, using Anna Karenina as the model. And thus, Anna Karina was born. It is said that throughout filming ‘Le Petit Soldat’, Godard fell more and more in love with his leading lady, and she with her director, and if you watch the film, it is immediately clear. Seldom has an actress been photographed so delicately, with such grace and such beauty, and with more of each as the film goes on. After wrapping, the two got married, but since love will tear us apart, by the time filming for ‘Le Mépris’ commenced two years later, the pair were drifting apart, and divorce was merely a question of time. Anna Karina, still acting well into the 21st century, would go on to become a true icon of the silver screen, and although she never made the leap to Hollywood, she remains to this day the face of the French New Wave. For her work with Godard, together, they made arguably the most influential body of work in the history of cinema.

‘Le Mépris’ is about a lot of things: death, a couple in love, a remake of ‘The Odyssey’, mortality, and the same couple falling apart. While the faces on the screen falling out of love are Brigitte Bardot’s (Camille) and Michel Piccoli’s (Paul), the pair merely stand in for Godard and Karina. Bardot recalls in her memoir that Godard asked her to act like Anna Karina and, famous for writing an actor’s dialogue on the spot and telling them to repeat it, he even recited Karina’s own words and phrases for Bardot to call back to the camera. Scenes filmed in the empty & decaying backlots of Cinecittà (Rome’s sprawling film studio), torn posters of Godard’s own films with Karina can be seen in the background. Bardot’s short, black wig that she wears around the empty apartment, temporarily inhabited by the estranging couple, quite purposefully resembles the one worn by Karina in 1962’s ‘My Life to Live’. Piccoli’s hat, which he is seldom seen without, is even one of Godard’s own. The story itself, has a feeling of finality to it, and although the ‘end’ of the French New Wave was still a few years away, with ‘Le Mépris’, Godard signalled the beginning of the end of the movement, and as he liked to call it, the end of cinema. Godard would grow increasingly disillusioned with the sorts of films he had raised himself on, and the sorts of films his colleagues continued to make, and more and more his movies would start to question the tropes and cliches that Classical Hollywood movies had propped themselves up upon. His disillusionment towards love, and towards cinema, are on full display in ‘Contempt’, and not once is an attempt made to hide it. The movie acts as a microphone for Godard to speak about marriage, love, and the state of his beloved cinema. And he uses his own marriage, his own lost love, his own feelings towards his medium, for you to hear it.

Godard, like all the greatest movie makers, used cinema to say what he wanted to. What set him apart from the rest, is that he used his own voice to say it. Whether it’s using (and I don’t mean that nefariously, although you may perhaps disagree) those he loved and that which he knew, or using hushed tones to narrate the story in his own voice, as in 1967’s ‘Two or Three Things I Know About Her’, Godard’s fingerprint on his movies feels more like a defining characteristic than an a mere aside.

Lines between life and art were perpetually blurred with Godard. While this may seem common practice now, never had it been done so openly before. Prior to the French New Wave, directors hid behind genre conventions and snuck their own philosophies and feelings in through the back door, such that they would go largely unnoticed, and the sense of a director’s personality behind the films in his oeuvre would become a metric for ‘good’ directors. But with the New Wave’s interminable linking of the film with the book, the director with the author, the director’s life became valuable material for the treatment of the film, and the product became ever more personal.

The greatest artists throughout history drew upon their own lives, and Mark Twain put it best when he condensed advice on writing into ‘write what you know’. In all art forms it is a given that one’s own life and consciousness is the well from which great ideas spring, but until Godard, who once stated, ‘I only like films that resemble their creators’, the same was never held true for film. The sentiment shared by George Peppard’s character in ‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s’, that every writer’s first book is autobiographical, was an idea that always intrigued me. Perhaps I’m a narcissist, but the day I realised that like literature, painting or music, movies too could sprout from the soil of one’s own misery, happiness, or anything else in-between, that the folly of one’s own life was sometimes the only material necessary, was the same day I caught a peek of paradise through the grey skies of life. And for that I’m not sure whether to love or to loathe Jean-Luc Godard. Frankly I’m not sure which way you should swing on it either.

You may also like

THE TEN GREATEST FILMS: OF ALL TIME

“Film is like a battleground. There’s love, hate, action, violence, death… In one

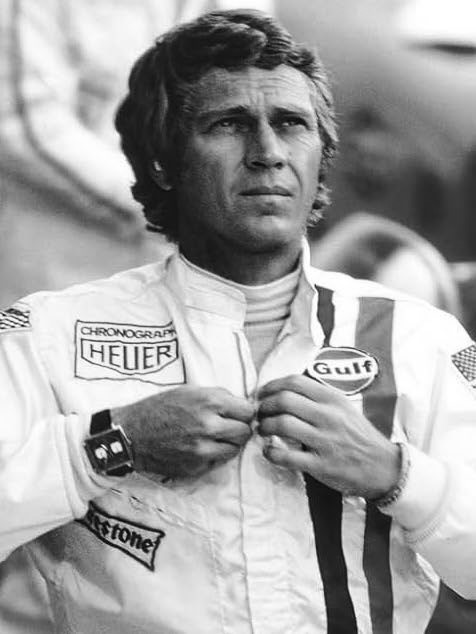

A MAN & HIS MACHINE: JANUARY

“When you’re racing, it’s life. Anything that happens before or after is just wa

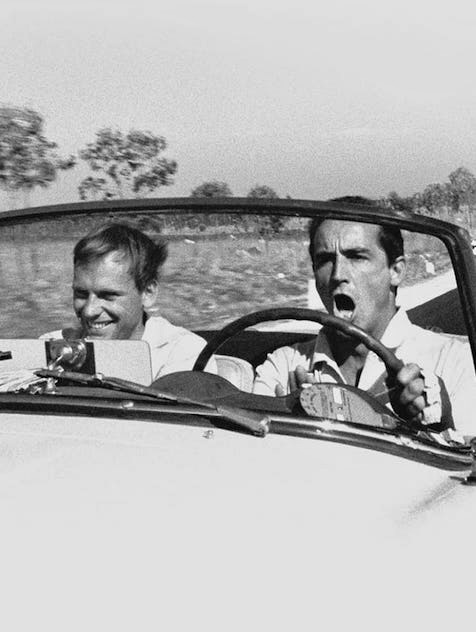

A ROAD OF NO RETURN: MAY

In life, it often is said, there’re two types of people. On the one hand,

Post a comment