THE REBEL: PETER BOGDANOVICH

“There are no ‘old’ movies.

Only movies you have already seen and ones you haven’t.”

Much has been written about Peter Bogdanovich in the last few years, but curiously little has been added to the books of film history since his death, last year, on January 6th. Something of a celebrity during the days of director as star, his rise and fall has been documented until the cows came well and truly home. The affair with his first leading lady that broke up his marriage was well publicised, and following three box-office knockouts in a row – three total outliers in the rough and raucous market of the 1970’s – his subsequent three flops made him Hollywood’s favourite target. After a failed attempt at showcasing cinema’s silent origins in 1976’s ‘Nickelodeon’, Bogdanovich took some time off, started again from square one, and fell in love. When Dorothy Stratten was murdered nine months into their relationship, Bogdanovich spiralled. He wrote a book about her, named ‘The Killing of a Unicorn’, and didn’t make a movie for five years. And while he’d continue making movies well into his seventies, he’d never again swing quite the way he did first time out the gate. It is difficult to write of Peter Bogdanovich’s legacy without writing about his personal life, and it is largely that which has been detailed and documented in recent years. While he is far from a household name, Mr. Bogdanovich very much holds his place in film history, and holds more than just a place in this celluloid pumping heart of mine.

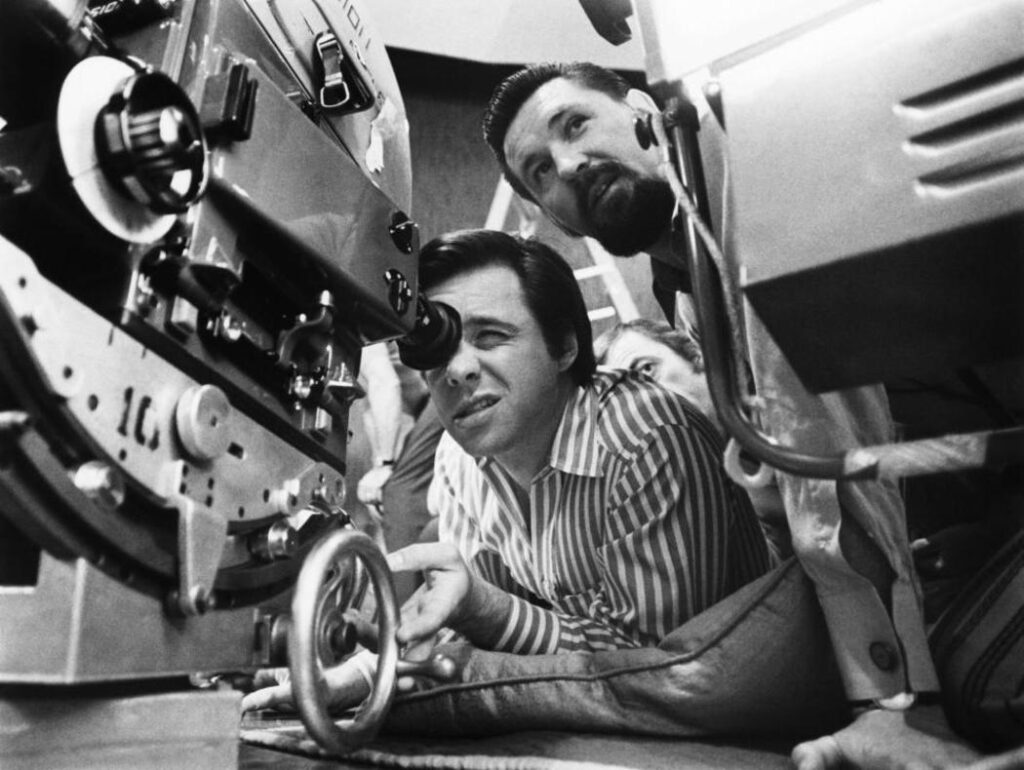

New York born in 1939, Bogdanovich was raised and grazed on the Golden Era of movies. After studying acting under Stella Adler (whose alumni include Brando & de Niro), he moved on to directing theatre. From there writing about movies, then writing movies, and in 1968, directed his first feature film, ‘Targets’, – a startlingly pertinent ‘modern-day’ thriller about a young, innocent boy, turned mass murderer. Before he was given that opportunity, however, it was Bogdanovich’s byline that first garnered attention from inside the seemingly impenetrable walls of moviemaking, and it was as much what he wrote about, as it was the way he wrote, that saw his name rise in stock.

The sixties represented the beginning of a new era for Hollywood, and therefore for movies. Studios were losing control, the Hays Code (censorship) was losing its grip, and America was losing its mind. Foreign films started to be shown regularly outside of their respective countries, and the conventional wisdom was that Alfred Hitchcock, along with almost every other Hollywood director, was little more than a cheap entertainer. Slow, meandering films by European filmmakers, who shall remain nameless, were thought to be the closest to art that cinema had come. Bogdanovich didn’t agree. He took it upon himself to challenge the consensus that America was lagging behind in its most native art form. Though, it wasn’t his contemporary films that he went to bat for, instead, it was the films he loved, the films he grew up on, the Hollywood films of the 1930’s, 40’s and fifties. A precocious cinephile; at the ludicrously tender age of 21, he was asked to write the monograph for MOMA’s first retrospective on ‘The Cinema of Orson Welles’. When Bogdanovich asked the museum’s head programmer why he hadn’t written it himself, the response was indicative of public opinion – “I don’t much care for Orson Welles”. Parallel retrospectives on Alfred Hitchcock and Howard Hawks followed, and Bogdanovich took public opinion to task. Eventually, Film Journal came knocking, and Esquire, then in its heyday, came and knocked harder.

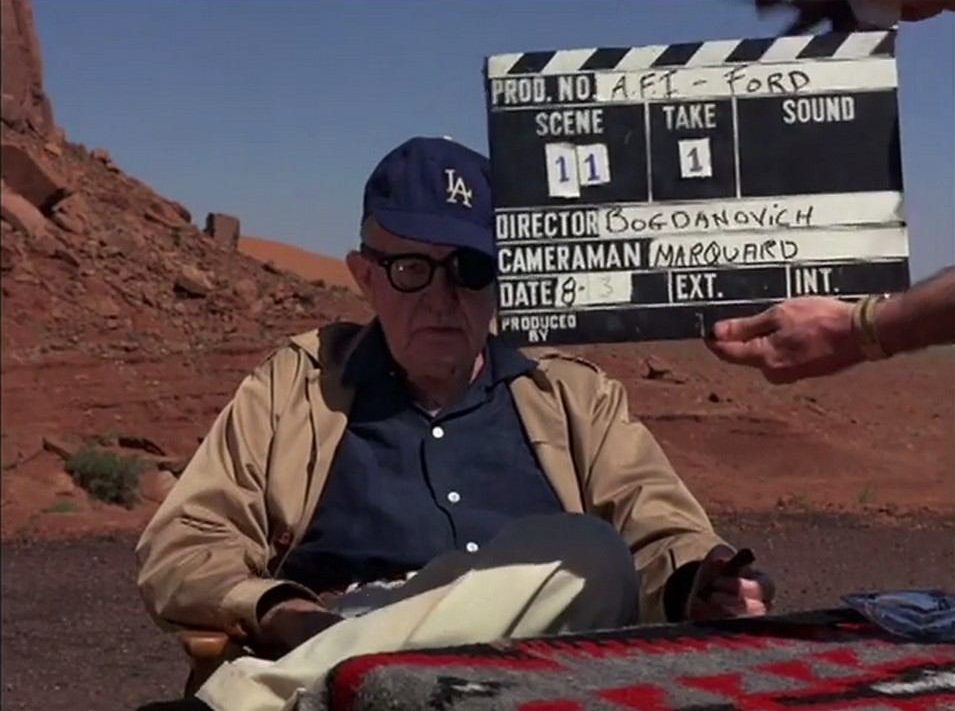

After some sage advice from director Frank Tashlin that movies were made in Los Angeles, not New York, Bogdanovich packed up and split for the Golden Coast. Thanks to a chance meeting, through an even chancier friend, Peter met low-budget producer king, Roger Corman. Through Corman, he found himself helping out on set, taking whatever work he could: script re-writing, second unit photography, art direction, editing. Simultaneously, due to his increasingly high regard as film journalist, Bogdanovich also found himself on the sets of his idols, among them Howard Hawks and John Ford, tasked with interviewing and covering his idols’ twilight years in the picture making business. Not content with the saying, “They don’t make them like they used to”, and owing to his unbridled love for the movies of yesteryear, Bogdanovich vowed that one day, when he got the chance, he would do exactly that, and make them exactly how they used to. Seeking out the companionship of his favourite directors, who were mostly still living in & around Los Angeles, Bogdanovich was finding out just how they did used to make them, and getting it straight from the horse’s mouth.

All that Bogdanovich learnt would eventually find its way into his books, and it is here, with these books in mind, that Bogdanovich made his curtained entrance into my life. While I may hasten to, I find it necessary to add some context of the more personal variety. Until about nineteen I had absolutely no interest in movies. Aside from rewatching ‘Back to the Future’ repeatedly, for its magical depiction of mid century American life, I averaged between six to eight movies per year. Then, through a fascination with the cultural endurance of Audrey Hepburn, I was introduced to ‘old’ movies. I devoured her filmography, excluding those dressed up in monochromatic colours, but eventually, the desire to watch her first movie, 1953’s ‘Roman Holiday’ outweighed any prejudice I had against its colour scheme. I forgave black & white’s primitivity and pressed play on William Wyler’s romantic-comedy classic. I found it so fantastical, that as the credits rolled I vowed never to watch a film in colour again. For a few short years I would only watch movies pre-dating 1969, and for a while really wouldn’t watch anything made in colour, irrespective of its birthdate. That spell was broken, however, for my both burgeoning, and burdening love for musicals of the 1950’s. Fast forward another year or so, and the conclusions I had reached about life and all its meaning excluded the possibility of doing anything other than making, or at least trying to make, some movies of my own.

But how? Where does one begin when making a movie? Where does one begin when trying to learn where to begin when making a movie? Although by this point I was fairly entrenched in the world of film, I couldn’t help but feel like I was staring at the top of a mountain, standing somewhere in a ditch, somewhere below the bottom. More pressing than that, was what I had long, subconsciously, deemed an insurmountable obstacle. How could I ever expect to make movies in today’s day and age, when I myself don’t like today’s movies and wouldn’t even watch them? Surely that barrier to entry was so fundamentally a barrier, that I was justified in my ignorance. Naturally I’d only ever wish to make movies that resembled, in some way, those that made me fall in love with movies in the first place, those movies that were made generations before I was. After a few months of weighing up the situation at hand, I stumbled across a name that had cropped up a few times before. I knew Peter Bogdanovich was a director, but I also knew that he was part of the ‘New Wave Hollywood’, which put his movies in a category (post-69) that I had no desire to explore. Thus, I had up until that point ignored any idle curiosity as to who this gentleman was. However, this time, I gave my principles the curve. And while that may sound like something resembling growth, the real reason I decided to look into the matter, was because his name was connected not with a film, but with a book he had written. Alfred Hitchcock was unequivocally one of the few, true, masters of cinema, and the first step in my quest to answer the questions that began this paragraph was to acquire all available literature on the names I knew I liked. ‘Who the Devil Made it’. Conversations with legendary filmmakers, it said, including one with Alfred Hitchcock. I went out to try and buy the book, but couldn’t find it anywhere. I resorted to the internet, and decided I was not willing to pay that much for a beat and bruised copy of a book of interviews. Instead, I set about doing a little research on Mr. Bogdanovich, the director, and apparent author. What I found would change the course of a great many things, including the amount of money I was willing to spend on a book.

Bogdanovich wrote several books, including interviews with actors, memories of going to the movies, books of published articles, books of unpublished articles, but it is the aforementioned book, ‘Who the Devil Made it’, a book over eight hundred pages in length, of his discussions with over a dozen classical Hollywood directors, that remains to me, what a certain Holy book remains to others. Like the painters of the Golden Gate Bridge who paint from one end to the other, then go back and start repainting it again, over the last three years I have read and reread his book, filling it every time with more annotations and more highlights. Many things came of my reading this book, and even though by the time I made the first round from cover to cover I had not yet watched any of his own movies, the fact that I was reading about someone asking his idols questions that I would ask mine, who went not to film school but instead to the movie theatre, who had total disregard for the movies of his time and adamantly stuck to what he loved most, was all the green lighting and validation I ever needed. Put simply, I was staring face to face with someone who, fifty years earlier, had done exactly what I’d deemed categorically impossible only that morning over breakfast.

One of the more indirect consequences of seeing Bogdanovich getting to know his heroes, was the realisation that each director’s own personality could be seen in their films. And not only that it could be, but that was a defining characteristic of the great directors of Hollywood’s Golden Era. The French even used it as a standardised metric to judge the validity of a director and named it ‘politique des auteurs’ (auteur theory). John Ford, when asked how he shot a magnificent land rush sequence in one of his early movies, replied, ‘with a camera’. Ford’s movies were as no nonsense and directorially straight forward as he was. Often cold and impenetrable on the surface, they were nevertheless often sentimental and heart-warming on the inside. Ford’s briskness was often betrayed, and the hard drinking Irishman’s soft sensibility would peak out in interviews at times when he just couldn’t help it.

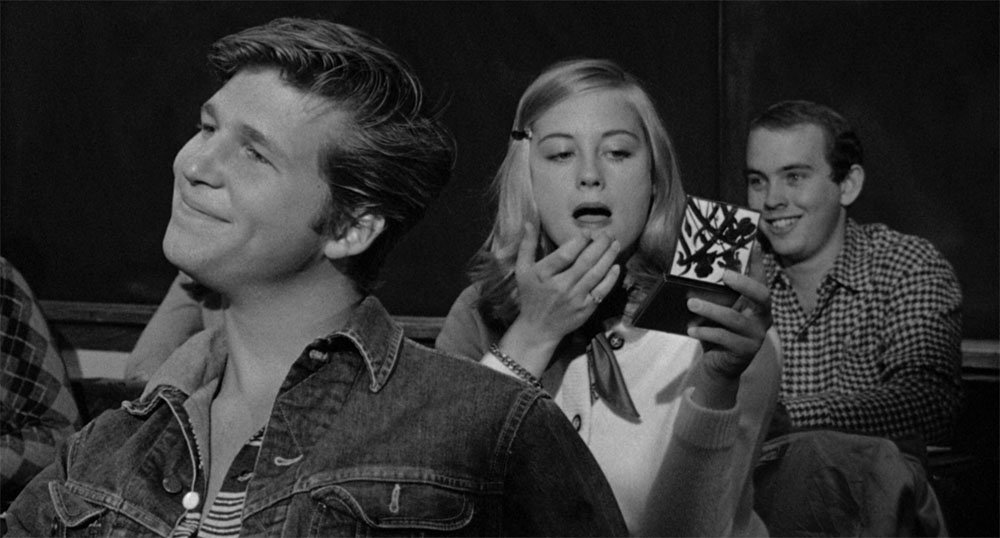

When finally I got round to watching Bogdanovich’s own movies, everything clicked into place. Everything about his movies reflected the style, the grace, the feeling of the movies he loved so dearly. The takes were long and uninterrupted, the angles were simple and set-ups unfussy. His films had clear narratives that adhered to a strict classical structure and everything always paid off in the end. Cuts were made only when necessary and, perhaps most importantly, stories were told visually; shared glances between the two leads in-between their lines told you more about their feelings for each other than any outspoken declaration of love ever could. Now, the director obviously couldn’t, and didn’t, just recreate his favourite classical movies, nor was he in the business of recreating exact shots (à la Tarantino), but he took the essence of them, their unpretentious nature and grace, while mixing them in with necessitating contemporaneous factors. He would never be able to cast a mid-thirties Cary Grant, nor an early-thirties Katharine Hepburn while planning his third film, a blisteringly fast-paced comedy titled ‘What’s Up Doc?’. Nevertheless, he used their definitive performances in the archetypical screwball comedy, 1938’s ‘Bringing Up Baby’ as templates, translating the story, and the characters, into a modern context. The result was Bogdanovich’s follow up to his Oscar winning drama, a comedy classic, and the third highest grosser of 1972. And for reference, dared to do it in the same year Coppola was making ‘The Godfather’.

Bogdanovich did certain things especially well: his visual compositions were painterly, his use of the long shot compared to Ford’s (who did for the long shot what Shakespeare did for the theatre), his ability to hop between genres was up there with the greatest of genre-hoppers, and stylistically, had in abundance that one word I find myself going back to – grace. However, one thing stands out to me when watching the best of Peter Bogdanovich’s movies, and that is his ability to tell a story that is both heart warming, at once happy yet simultaneously wistful, and melancholy. His 1981 romantic-comedy, ‘They All Laughed’, being the best example of this duality, and in-turn, quite honestly my favourite movie of all time. I leave no other film torn between the belief the true love does in fact still exist, but that it can hurt so much that, sometimes you’d rather it didn’t. Bogdanovich has frequently called it his favourite, as have most your favourite directors, and the movie of his that most represents himself. He even made up John Ritter’s character, Charles, to look like himself, whilst Charles fell love with Dolores, Dorothy Stratten’s character, the very woman Bogdanovich had fallen in love with off-screen.

There can be no question that Bogdanovich made mistakes. Both personally, and professionally, his judgement can be called into question on more than one occasion. It is curious that someone who burst onto the Hollywood scene with the vigour that he did, is so largely unknown today. For reference, his second and breakout movie, ‘The Last Picture Show’, was called “the most impressive work of a young director since Citizen Kane”. He was not only offered, but turned down, directing such classics as ‘The Godfather’, ‘French Connection’, and ‘Chinatown’. In the seventies, a decade which conjures up names such as Scorsese, Coppola and Friedkin, Peter Bogdanovich was once king. His first three hits, rounded off by 1973’s ‘Paper Moon’, were such successes, that he was referred to once by the studio’s head as the Babe Ruth of movies. But Bogdanovich’s tendency to fall in love, and hopelessly so, seemed to have clouded his judgement on his adaptation of Henry James’ ‘Daisy Miller’. Hubris, naturally, also has a large part to play here. Since he had come out the gate swinging, Hollywood was more eager than a famished shark to smell blood. And blood it smelt.

The general consensus is that his downfall, really, was his own stubbornness and reluctance to ‘move on’. After he passed away, I was reading a piece about him in the LA Times, and the actress Imogen Poots said something about him which I think summed it up, and simultaneously, sums up why there shall always be a place for him in my heart: “If you look at Scorsese, he has adapted constantly to this climate and this era – he had Kanye West in the ‘Wolf of Wall Street’ trailer. But with Peter, there’s more a sense of, “No, the films of the ‘20s and the ‘30s were the best. They really don’t make them like they used to – so I’m going to try and do that’”.

And do that he did, and for it, he has not only the eternal gratitude of this moviemaker here, but too the title of cinema’s most conservative rebel.

You may also like

THE BIG SLEEP: PROGRAMME NOTE

“Nice state of affairs when a man has to indulge his vices by proxy.” Audiences attendi

THE TEN GREATEST FILMS: OF ALL TIME

“Film is like a battleground. There’s love, hate, action, violence, death… In one

A MAN & HIS MACHINE: JANUARY

“When you’re racing, it’s life. Anything that happens before or after is just wa

Post a comment